Tennessee

|

Tennessee

ᏔᎾᏏ

(Cherokee)

|

|

|---|---|

| State of Tennessee | |

| Nickname:

The Volunteer State

[1]

|

|

| Motto(s):

Agriculture and Commerce

|

|

| Anthem:Eleven songs | |

Map of the United States with Tennessee highlighted

|

|

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Southwest Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | June 1, 1796(16th) |

| Capital (and largest city) |

Nashville[2] |

| Largest metroandurbanareas | Nashville |

| Government | |

| •Governor | Bill Lee(R) |

| •Lieutenant Governor | Randy McNally(R) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| •Upper house | Senate |

| •Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Tennessee Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators | Marsha Blackburn(R) Bill Hagerty(R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 8 Republicans 1Democrat(list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 42,181 sq mi (109,247 km2) |

| • Land | 41,235 sq mi (106,898 km2) |

| • Water | 909 sq mi (2,355 km2) 2.2% |

| • Rank | 36th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 440 mi (710 km) |

| • Width | 120 mi (195 km) |

| Elevation | 900 ft (270 m) |

| Highest elevation | 6,643 ft (2,025 m) |

| Lowest elevation | 178 ft (54 m) |

| Population

(2023)

|

|

| • Total | 7,126,489[4] |

| • Rank | 15th |

| • Density | 171.0/sq mi (65.9/km2) |

| • Rank | 20th |

| •Median household income | $58,516 (2,021)[4] |

| • Income rank | 41st |

| Demonyms | Tennessean Big Bender(archaic) Volunteer(historical significance) |

| Language | |

| •Official language | English |

| •Spoken language | Language spoken at home[6] |

| Time zones | |

| East Tennessee | UTC−05:00(Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00(EDT) |

| MiddleandWest | UTC−06:00(Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00(CDT) |

| USPS abbreviation |

TN

|

| ISO 3166 code | US-TN |

| Traditional abbreviation | Tenn. |

| Latitude | 34°59′ N to 36°41′ N |

| Longitude | 81°39′ W to 90°19′ W |

| Website | tn |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Poem | "Oh Tennessee, My Tennessee" byWilliam Lawrence |

| Slogan | "Tennessee—America at its best" |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | Tennessee cave salamander |

| Bird | Northern mockingbird Bobwhite quail |

| Butterfly | Zebra swallowtail |

| Fish | Channel catfish Smallmouth bass |

| Flower | Iris Passion flower Tennessee echinacea |

| Insect | Firefly Lady beetle Honey bee |

| Mammal | Tennessee Walking Horse Raccoon |

| Reptile | Eastern box turtle |

| Tree | Tulip poplar Eastern red cedar |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Milk |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Firearm | Barrett M82[7] |

| Food | Tomato |

| Fossil | Pterotrigonia (Scabrotrigonia) thoracica |

| Gemstone | Tennessee River pearl |

| Mineral | Agate |

| Rock | Limestone |

| Tartan | Tennessee State Tartan |

| State route marker | |

|

|

| State quarter | |

Released in 2002

|

|

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Tennessee(/ˌtɛnɪˈsiː/TEN-iss-EE,locally/ˈtɛnɪsi/TEN-iss-ee),[8][9][10]officially theState of Tennessee, is a landlockedstatein theSoutheasternregion of theUnited States. It bordersKentuckyto the north,Virginiato the northeast,North Carolinato the east,Georgia,Alabama, andMississippito the south,Arkansasto the southwest, andMissourito the northwest. Tennessee is the36th-largestby area and the15th-most populousof the 50 states. Tennessee is geographically, culturally, and legally divided into threeGrand DivisionsofEast,Middle, andWest Tennessee.Nashvilleis the state's capital and largest city, and anchors its largest metropolitan area. Other major cities includeMemphis,Knoxville,Chattanooga, andClarksville. Tennessee's population as of the2020 United States censusis approximately 6.9 million.[11]

Tennessee is rooted in theWatauga Association, a 1772 frontier pact generally regarded as the first constitutional government west of theAppalachian Mountains.[12]Its name derives fromTanasi(ᏔᎾᏏ), aCherokeetown in the eastern part of the state that existed before the first European American settlement.[13]Tennessee was initially part of North Carolina, and later theSouthwest Territory, before its admission to the Union as the 16th state on June 1, 1796. It earned the nickname "The Volunteer State" early in its history due to a strong tradition of military service.[14]Aslave stateuntil theAmerican Civil War, Tennessee was politically divided, with most of its western and middle parts supporting theConfederacy, and most of the eastern region harboringpro-Unionsentiment. As a result, Tennessee was the last state to officiallysecedefrom the Union and join theConfederacy, and the first formerConfederatestate readmitted to the Union after the war had ended during theReconstruction era.[15]

During the 20th century, Tennessee transitioned from a predominantly agrarian society to a more diversified economy. This was aided in part by massive federal investment in theTennessee Valley Authority(TVA) and the city ofOak Ridge, which was established duringWorld War IIto house theManhattan Project's uranium enrichment facilities for the construction of theworld's first atomic bombs. After the war, theOak Ridge National Laboratorybecame a key center of scientific research. In 2016, the elementtennessinewas named for the state, largely in recognition of the roles played by Oak Ridge,Vanderbilt University, and theUniversity of Tennesseein its discovery.[16]Tennessee has also played a major role in the development of many forms ofpopular music, includingcountry,blues,rock and roll,soul, andgospel.

Tennessee has diverse terrain and landforms, and from east to west, contains a mix of cultural features characteristic ofAppalachia, theUpland South, and theDeep South. TheBlue Ridge Mountainsalong the eastern border reach some of the highest elevations in eastern North America, and theCumberland Plateaucontains many scenic valleys andwaterfalls. The central part of the state is marked by cavernous bedrock and irregular rolling hills, and level, fertile plains define West Tennessee. The state is twice bisected by theTennessee River, and theMississippi Riverforms its western border. Its economy is dominated by thehealth care,music,finance,automotive,chemical,electronics, andtourismsectors, andcattle,soybeans,corn,poultry,tobacco, andcottonare its primary agricultural products.[17]TheGreat Smoky Mountains National Park, the nation's most visited national park, is in eastern Tennessee.[18]

Etymology

Tennessee derives its name most directly from theCherokeetown ofTanasi(or "Tanase", insyllabary: ᏔᎾᏏ) in present-dayMonroe County, Tennessee, on the Tanasi River, now known as theLittle Tennessee River. This town appeared on British maps as early as 1725. In 1567,Spanish explorerCaptainJuan Pardoand his party encountered aNative Americanvillage named "Tanasqui" in the area while traveling inland from modern-daySouth Carolina; however, it is unknown if this was the same settlement as Tanasi.[b]Recent research suggests that the Cherokees adapted the name from theYuchiwordTana-tsee-dgee, meaning "brother-waters-place" or "where-the-waters-meet".[20][21][22]The modern spelling,Tennessee, is attributed to GovernorJames Glenof South Carolina, who used this spelling in his official correspondence during the 1750s. In 1788, North Carolina created "Tennessee County", and in 1796, aconstitutional convention, organizing the new state out of theSouthwest Territory, adopted "Tennessee" as the state's name.[23]

History

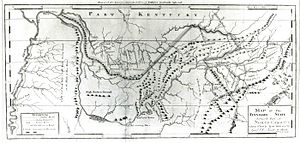

Pre-European era

The first inhabitants of Tennessee werePaleo-Indianswho arrived about 12,000 years ago at the end of theLast Glacial Period. Archaeological excavations indicate that the lower Tennessee Valley was heavily populated by Ice Agehunter-gatherers, and Middle Tennessee is believed to have been rich withgame animalssuch asmastodons.[24]The names of the cultural groups who inhabited the area before European contact are unknown, but archaeologists have named several distinct cultural phases, including theArchaic(8000–1000 BC),Woodland(1000 BC–1000 AD), andMississippian(1000–1600 AD) periods.[25]The Archaic peoples first domesticated dogs, and plants such assquash,corn,gourds, andsunflowerswere first grown in Tennessee during the Woodland period.[26]Later generations of Woodland peoples constructed the first mounds. Rapid civilizational development occurred during the Mississippian period, when Indigenous peoples developed organizedchiefdomsand constructed numerous ceremonial structures throughout the state.[27]

Spanish conquistadors who explored the region in the 16th century encountered some of the Mississippian peoples, including theMuscogee Creek,Yuchi, andShawnee.[28][29]By the early 18th century, most Natives in Tennessee had disappeared, most likely wiped out by diseases introduced by the Spaniards.[28]The Cherokee began migrating into what is now eastern Tennessee from what is now Virginia in the latter 17th century, possibly to escape expanding European settlement and diseases in the north.[30]They forced the Creek, Yuchi, and Shawnee out of the state in the early 18th century.[30][31]The Chickasaw remained confined to West Tennessee, and the middle part of the state contained few Native Americans, although both the Cherokee and the Shawnee claimed the region as their hunting ground.[32]Cherokee peoples in Tennessee were known by European settlers as theOverhill Cherokeebecause they lived west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[33]Overhill settlements grew along the rivers in East Tennessee in the early 18th century.[34]

Exploration and colonization

The first recorded European expeditions into what is now Tennessee were led by Spanish explorersHernando de Sotoin 1540–1541,Tristan de Lunain 1559, andJuan Pardoin 1566–1567.[35][36][37]In 1673, English fur traderAbraham Woodsent an expedition from theColony of VirginiaintoOverhill Cherokee territoryin modern-day northeastern Tennessee.[38][39]That same year, a French expedition led by missionaryJacques MarquetteandLouis Jollietexplored the Mississippi River and became the first Europeans to map the Mississippi Valley.[39][38]In 1682, an expedition led byRené-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La SalleconstructedFort Prudhommeon theChickasaw Bluffsin West Tennessee.[40]By the late 17th century, French traders began to explore the Cumberland River valley, and in 1714, under Charles Charleville's command, established French Lick, a fur trading settlement at the present location of Nashville near theCumberland River.[41][42]In 1739, the French constructedFort AssumptionunderJean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienvilleon the Mississippi River at the present location of Memphis, which they used as a base against the Chickasaw during the1739 Campaignof theChickasaw Wars.[43]

In the 1750s and 1760s,longhuntersfrom Virginia explored much of East and Middle Tennessee.[44]Settlers from theColony of South CarolinabuiltFort Loudounon theLittle Tennessee Riverin 1756, the first British settlement in what is now Tennessee and the westernmost British outpost to that date.[45][46]Hostilities erupted between the British and the Cherokees intoan armed conflict, and asiege of the fortended with its surrender in 1760.[47]After theFrench and Indian War, Britain issued theRoyal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settlements west of theAppalachian Mountainsin an effort to mitigate conflicts with the Natives.[48]But migration across the mountains continued, and the first permanent European settlers began arriving in northeastern Tennessee in the late 1760s.[49][50]Most of them wereEnglish, but nearly 20% wereScotch-Irish.[51]They formed theWatauga Associationin 1772, a semi-autonomous representative government,[52]and three years later reorganized themselves into theWashington Districtto support the cause of theAmerican Revolutionary War.[53]The next year, after an unsuccessful petition to Virginia, North Carolina agreed to annex the Washington District to provide protection from Native American attacks.[54]

In 1775,Richard Hendersonnegotiated a series of treaties with the Cherokee to sell the lands of the Watauga settlements atSycamore Shoalson the banks of theWatauga River. An agreement to sell land for theTransylvania Colony, which included the territory in Tennessee north of the Cumberland River, was also signed.[55]Later that year,Daniel Boone, under Henderson's employment, blazed a trail fromFort Chiswellin Virginia through theCumberland Gap, which became part of theWilderness Road, a major thoroughfare into Tennessee and Kentucky.[56]The Chickamauga, a Cherokee faction loyal to the British led byDragging Canoe, opposed the settling of the Washington District and Transylvania Colony, and in 1776 attackedFort Wataugaat Sycamore Shoals.[57][58]The warnings of Dragging Canoe's cousinNancy Wardspared many settlers' lives from the initial attacks.[59]In 1779,James RobertsonandJohn Donelsonled two groups of settlers from the Washington District to the French Lick.[60]These settlers constructedFort Nashborough, which they named forFrancis Nash, abrigadier generalof theContinental Army.[61]The next year, the settlers signed theCumberland Compact, which established a representative government for the colony called theCumberland Association.[62]This settlement later grew into the city of Nashville.[63]That same yearJohn Sevierled a group ofOvermountain Menfrom Fort Watauga to theBattle of Kings Mountainin South Carolina, where they defeated the British.[64]

Three counties of theWashington Districtbroke off fromNorth Carolinain 1784 and formed theState of Franklin.[65]Efforts to obtain admission to theUnionfailed, and the counties, now numbering eight, rejoined North Carolina by 1788.[66]North Carolina ceded the area to the federal government in 1790, after which it was organized into theSouthwest Territoryon May 26 of that year.[67]The act allowed the territory to petition for statehood once the population reached 60,000.[67]Administration of the territory was divided between the Washington District and the Mero District, the latter of which consisted of the Cumberland Association and was named for Spanish territorial governorEsteban Rodríguez Miró.[68]PresidentGeorge WashingtonappointedWilliam Blountas territorial governor.[69]The Southwest Territory recorded a population of 35,691 in thefirst United States censusthat year, including 3,417 slaves.[70]

Statehood and antebellum era

As support for statehood grew among the settlers, Governor Blount called for elections, which were held in December 1793.[71]The 13-member territorial House of Representatives first convened in Knoxville on February 24, 1794, to select ten members for the legislature's upper house, the council.[71]The full legislature convened on August 25, 1794.[72]In June 1795, the legislature conducted a census of the territory, which recorded a population of 77,263, including 10,613 slaves, and a poll that showed 6,504 in favor of statehood and 2,562 opposed.[73][74]Elections for a constitutional convention were held in December 1795, and the delegates convened in Knoxville on January 17, 1796, to begin drafting a state constitution.[75]During this convention, the name Tennessee was chosen for the new state.[23]The constitution was completed on February 6, which authorized elections for the state's new legislature, theTennessee General Assembly.[76][77]The legislature convened on March 28, 1796, and the next day, John Sevier was announced as the state's first governor.[76][77]Tennessee was admitted to the Union on June 1, 1796, as the 16th state and the first created from federal territory.[78][79]

Tennessee reportedly earned the nickname "The Volunteer State" during theWar of 1812, when 3,500 Tennesseans answered a recruitment call by the General Assembly for the war effort.[80]These soldiers, underAndrew Jackson's command, played a major role in the American victory at theBattle of New Orleansin 1815, the last major battle of the war.[80]Several Tennesseans took part in theTexas Revolutionof 1835–36, including GovernorSam Houstonand Congressman and frontiersmanDavy Crockett, who was killed at theBattle of the Alamo.[81]The state's nickname was solidified during theMexican–American Warwhen PresidentJames K. Polkof Tennessee issued a call for 2,800 soldiers from the state, and more than 30,000 volunteered.[82]

Between the 1790s and 1820s, additional land cessions were negotiated with the Cherokee, who had establisheda national governmentmodeled on theU.S. Constitution.[83][84]In 1818, Jackson and Kentucky governorIsaac Shelbyreached an agreement with the Chickasaw to sell the land between the Mississippi and Tennessee Rivers to the United States, which included all of West Tennessee and became known as the "Jackson Purchase".[85]The Cherokee moved their capital from Georgia to theRed Clay Council Groundsin southeastern Tennessee in 1832, due to new laws forcing them from their previous capital atNew Echota.[86]In 1838 and 1839, U.S. troopsforcibly removedthousands of Cherokees and their black slaves from their homes in southeastern Tennessee and forced them to march toIndian Territoryin modern-dayOklahoma. This event is known as theTrail of Tears, and an estimated 4,000 died along the way.[87][88]

As settlers pushed west of the Cumberland Plateau, a slavery-basedagrarian economytook hold in these regions.[89]Cotton planters used extensive slave labor on largeplantation complexesin West Tennessee's fertile and flat terrain after the Jackson Purchase.[90]Cotton also took hold in the Nashville Basin during this time.[90]Entrepreneurs such asMontgomery Bellused slaves in the production of iron in the Western Highland Rim, and slaves also cultivated such crops as tobacco and corn throughout the Highland Rim.[89]East Tennessee's geography did not allow for large plantations as in the middle and western parts of the state, and as a result, slavery became increasingly rare in the region.[91]A strongabolition movementdeveloped in East Tennessee, beginning as early as 1797, and in 1819,Elihu EmbreeofJonesboroughbegan publishing theManumission Intelligencier(laterThe Emancipator), the nation's first exclusively anti-slavery newspaper.[92][93]

Civil War

At the onset of theAmerican Civil War, most Middle and West Tennesseans favored efforts to preserve their slavery-based economies, but many Middle Tennesseans were initially skeptical of secession. In East Tennessee, most people favored remaining in the Union.[94]In 1860, slaves composed about 25% of Tennessee's population, the lowest share among the states that joined theConfederacy.[95]Tennessee provided more Union troops than any other Confederate state, and the second-highest number of Confederate troops, behind Virginia.[15][96]Due to its central location, Tennessee was a crucial state during the war and saw more military engagements than any state except Virginia.[97]

AfterAbraham Lincolnwas elected president in1860, secessionists in the state government led by GovernorIsham Harrissought voter approvalto sever ties with the United States, which was rejected in a referendum by a 54–46% margin in February 1861.[98]After the Confederateattack on Fort Sumterin April and Lincoln's call for troops in response, the legislature ratified an agreement to enter a military league with the Confederacy on May 7, 1861.[99]On June 8, with Middle Tennesseans having significantly changed their position, voters approved a second referendum on secession by a 69–31% margin, becoming the last state to secede.[100]In response, East Tennessee Unionists organizeda convention in Knoxvillewith the goal of splitting the region to form a new state loyal to the Union.[101]In the fall of 1861, Unionist guerrillas in East Tennesseeburned bridgesand attacked Confederate sympathizers, leading the Confederacy to invokemartial lawin parts of the region. Because of this, many southern unionists were sent fleeing to nearby Union states, particularly theborder stateofKentucky. Other southern unionists, who stayed in Tennessee after the state's secession, either resisted the Confederate cause or eventually joined it.[102]In March 1862, Lincoln appointed native Tennessean andWar DemocratAndrew Johnsonas military governor of the state.[103]

GeneralUlysses S. Grantand theU.S. Navycaptured the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers in February 1862 at the battles ofFort HenryandFort Donelson.[104]Grant then proceeded south to Pittsburg Landing and held off a Confederate counterattack atShilohin April in what was at the time the bloodiest battle of the war.[105]Memphis fell to the Union in June after anaval battleon the Mississippi River.[106]Union strength in Middle Tennessee was tested in a series of Confederate offensives beginning in the summer of 1862, which culminated in GeneralWilliam Rosecrans'sArmy of the Cumberlandrouting GeneralBraxton Bragg'sArmy of TennesseeatStones River, another one of the war's costliest engagements.[107]The next summer, Rosecrans'sTullahoma campaignforced Bragg's remaining troops in Middle Tennessee to retreat to Chattanooga with little fighting.[108]

During theChattanooga campaign, Confederates attempted to besiege the Army of the Cumberland into surrendering, but reinforcements from theArmy of the Tennesseeunder the command of Grant,William Tecumseh Sherman, andJoseph Hookerarrived.[109]The Confederates were driven from the city at the battles ofLookout MountainandMissionary Ridgein November 1863.[110]Despite Unionist sentiment in East Tennessee, Confederates held the area for most of the war. A few days after the fall of Chattanooga, Confederates led byJames Longstreetunsuccessfullycampaigned to take control of Knoxvilleby attacking Union GeneralAmbrose Burnside'sFort Sanders.[111]The capture of Chattanooga allowed Sherman to launch theAtlanta campaignfrom the city in May 1864.[112]The last major battles in the state came when Army of Tennessee regiments underJohn Bell Hoodinvaded Middle Tennesseein the fall of 1864 in an effort to draw Sherman back. They were checked byJohn SchofieldatFranklinin November and completely dispersed byGeorge ThomasatNashvillein December.[113]On April 27, 1865, theworst maritime disaster in American historyoccurred when theSultanasteamboat, which was transporting freed Union prisoners,explodedin the Mississippi River north of Memphis, killing 1,168 people.[114]

When theEmancipation Proclamationwas announced, Tennessee was largely held by Union forces and thus not among the states enumerated, so it freed no slaves there.[115]Andrew Johnson declared all slaves in Tennessee free on October 24, 1864.[115]On February 22, 1865, the legislature approved an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting slavery, which was approved by voters the following month, and would go into effect later on in the year. This made Tennessee the only Southern state to abolish slavery at the time.[116][117]Tennessee ratified theThirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery in every state, on April 7, 1865,[118]and theFourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to former slaves, on July 18, 1866. Both amendments went into effect after Tennessee's readmission to the union due to the fact that other states had not yet ratified it.[119]Johnson became vice president when Lincoln wasreelected, and president after Lincoln'sassassinationin May 1865.[103]On July 24, 1866, Tennessee became the first Confederate state to have its elected members readmitted to Congress.[120]

Reconstruction and late 19th century

The years after the Civil War were characterized by tension and unrest between blacks and former Confederates, the worst of which occurred inMemphis in 1866.[121]Because Tennessee had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment before its readmission to the Union, it was the only former secessionist state that did not have a military governor duringReconstruction.[119]TheRadical Republicansseized control of the state government toward the end of the war, and appointedWilliam G. "Parson" Brownlowgovernor. Under Brownlow's administration from 1865 to 1869, the legislature allowed African American men to vote, disenfranchised former Confederates, and with martial law, took action against theKu Klux Klan, which was founded in December 1865 inPulaskias a vigilante group to advance former Confederates' interests.[122]In 1870,Southern Democratsregained control of the state legislature,[123]and over the next two decades, passedJim Crow lawsto enforceracial segregation.[124]A total of 251lynchings, predominately of Black people, took place in Tennessee.[125][126]

A number of epidemics swept through Tennessee in the years after the Civil War, includingcholerain 1873, which devastated the Nashville area,[127]andyellow feverin 1878, which killed more than one-tenth of Memphis's residents.[128][129]Reformers worked to modernize Tennessee into a "New South" economy during this time. With the help of Northern investors, Chattanooga became one of the first industrialized cities in the South.[130]Memphis became known as the "Cotton Capital of the World" during the late 19th century, and Nashville, Knoxville, and several smaller cities saw modest industrialization.[130]Northerners also began exploiting the coalfields and mineral resources in the Appalachian Mountains. To pay off debts and alleviate overcrowded prisons, the state turned toconvict leasing, providing prisoners to mining companies asstrikebreakers, which was protested by miners forced to compete with the system.[131]An armed uprising in the Cumberland Mountains known as theCoal Creek Warin 1891 and 1892 resulted in the state ending convict leasing.[132][133]

Despite New South promoters' efforts, agriculture continued to dominate Tennessee's economy.[134]The majority of freed slaves were forced intosharecroppingduring the latter 19th century, and many others worked as agricultural wage laborers.[135]In 1897, Tennessee celebrated its statehood centennial one year late with theTennessee Centennial and International Expositionin Nashville.[136]Afull-scale replicaof theParthenoninAthenswas designed by architectWilliam Crawford Smithand constructed for the celebration, owing to the city's reputation as the "Athens of the South".[137][138]

Early 20th century

Due to increasing racial segregation and poor standards of living, many black Tennesseans fled to industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest as part of the first wave of theGreat Migrationbetween 1915 and 1930.[139]Many residents of rural parts of Tennessee relocated to larger cities during this time for more lucrative employment opportunities.[130]As part of theTemperance movement, Tennessee became the first state in the nation to effectively ban the sale, transportation, and production of alcohol in a series of laws passed between 1907 and 1917.[140]DuringProhibition, illicit production ofmoonshinebecame extremely common in East Tennessee, particularly in the mountains, and continued for many decades afterward.[141]

Sgt.Alvin C. YorkofFentress Countybecame one of the most famous and honored American soldiers ofWorld War I. He received the CongressionalMedal of Honorfor single-handedly capturing an entire German machine gun regiment during theMeuse–Argonne offensive.[142]On July 9, 1918, Tennessee suffered theworst rail accident in U.S. historywhen two passenger trainscollided head onin Nashville, killing 101 and injuring 171.[143]On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th and final state necessary to ratify theNineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave women theright to vote.[144]In 1925,John T. Scopes, a high school teacher inDayton, wastried and convictedfor teachingevolutionin violation of the state's recently passedButler Act.[145]Scopes was prosecuted by formerSecretary of Stateand presidential candidateWilliam Jennings Bryanand defended by attorneyClarence Darrow. The case was intentionally publicized,[146]and highlighted thecreationism-evolution controversyamong religious groups.[147]In 1926, Congress authorized the establishment ofa national parkin theGreat Smoky Mountains, which was officially established in 1934 and dedicated in 1940.[148]

When theGreat Depressionstruck in 1929, much of Tennessee was severely impoverished even by national standards.[149]As part of PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt'sNew Deal, theTennessee Valley Authority(TVA) was created in 1933 to provide electricity, jobs, flood control, improved waterway navigation, agricultural development, and economic modernization to theTennessee River Valley.[150]The TVA built several hydroelectric dams in the state in the 1930s and 1940s, which inundated communities and thousands of farmland acreage, and forcibly displaced families viaeminent domain.[151][152]The agency quickly grew into the country's largest electric utility and initiated a period of dramatic economic growth and transformation that brought many new industries and employment opportunities to the state.[150][153]

DuringWorld War II, East Tennessee was chosen for the production of weapons-gradefissileenriched uraniumas part of theManhattan Project, aresearch and developmentundertaking led by the U.S. to produce the world's firstatomic bombs. Theplanned communityofOak Ridgewas built to provide accommodations for the facilities and workers; the site was chosen due to the abundance of TVA electric power, its low population density, and its inland geography and topography, which allowed for the natural separation of the facilities and a low vulnerability to attack.[154][155]TheClinton Engineer Workswas established as the production arm of the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, which enriched uranium at three major facilities for use in atomic bombs. The first of the bombs was detonated inAlamogordo, New Mexico, in a test code-namedTrinity, and the second, nicknamed "Little Boy", wasdropped on Imperial Japanat the end of World War II.[156]After the war, theOak Ridge National Laboratorybecame an institution for scientific and technological research.[157]

Mid-20th century to present

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional inBrown v. Board of Educationin 1954,Oak Ridge High Schoolin 1955 became the first school in Tennessee to beintegrated.[158]The next year, nearbyClinton High Schoolwas integrated, andTennessee National Guardtroops were sent in after pro-segregationists threatened violence.[158]Between February and May 1960, aseries of sit-insat segregated lunch counters in Nashville organized by theNashville Student Movementresulted in the desegregation of facilities in the city.[159]On April 4, 1968,James Earl Rayassassinatedcivil rights leaderMartin Luther King Jr.in Memphis.[160]King had traveled there to supportstriking African American sanitation workers.[161][162]

The 1962U.S. Supreme CourtcaseBaker v. Carrarose out of a challenge to the longstanding rural bias of apportionment of seats in the Tennessee legislature and established the principle of "one man, one vote".[163][164]The construction ofInterstate 40through Memphis became a national talking point on the issue ofeminent domainandgrassroots lobbyingwhen theTennessee Department of Transportation(TDOT) attempted to construct the highway through the city'sOverton Park. Alocal activist groupspent many years contesting the project, and in 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the group and established the framework forjudicial reviewof government agencies in thelandmark caseofCitizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe.[165][166]TVA's construction of theTellico Damin Loudon County became the subject of national controversy in the 1970s when the endangeredsnail darterfish was reported to be affected by the project. After lawsuits by environmental groups, the debate was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court caseTennessee Valley Authority v. Hillin 1978, leading to amendments of theEndangered Species Act.[167]

The1982 World's Fairwas held in Knoxville.[168]Also known as the Knoxville International Energy Exposition, the fair's theme was "Energy Turns the World". The exposition was one of the most successful, and the most recent world's fair to be held in the U.S.[169]In 1986, Tennessee held a yearlong celebration of the state's heritage and culture called "Homecoming '86".[170][171]Tennessee celebrated its bicentennial in 1996 with a yearlong celebration called "Tennessee 200". A new state park that traces the state's history,Bicentennial Mall, was opened at the foot of Capitol Hill in Nashville.[172]The same year, thewhitewater slalomevents at the AtlantaSummer Olympic Gameswere held on theOcoee RiverinPolk County.[173]

In 2002, Tennessee amended its constitution to establish alottery.[174]In 2006, the state constitutionwas amendedto outlawsame-sex marriage. This amendment was invalidated by the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court caseObergefell v. Hodges.[175]On December 23, 2008, thelargest industrial waste spill in United States historyoccurred at TVA'sKingston Fossil Plantwhen more than 1.1 billion gallons ofcoal ashslurry was accidentally released into theEmoryandClinch Rivers.[176][177]The cleanup cost more than $1 billion and lasted until 2015.[178]

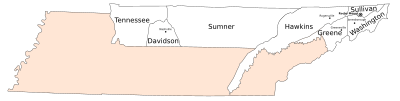

Geography

Tennessee is in theSoutheastern United States. Culturally, most of the state is considered part of theUpland South, and the eastern third is part ofAppalachia.[179]Tennessee covers roughly 42,143 square miles (109,150 km2), of which 926 square miles (2,400 km2), or 2.2%, is water. It is the16th smallest statein land area. The state is about 440 miles (710 km) long from east to west and 112 miles (180 km) wide from north to south. Tennessee is geographically, culturally, economically, and legally divided into threeGrand Divisions:East Tennessee,Middle Tennessee, andWest Tennessee.[180]It borders eight other states:KentuckyandVirginiato the north,North Carolinato the east,Georgia,Alabama, andMississippion the south, andArkansasandMissourion the west. It is tied with Missouri as the state bordering the most other states.[181]Tennessee is trisected by theTennessee River, and its geographical center is inMurfreesboro. Nearly three–fourths of the state is in theCentral Time Zone, with most of East Tennessee onEastern Time.[182]The Tennessee River forms most of the division between Middle and West Tennessee.[180]

Tennessee's eastern boundary roughly follows the highest crests of theBlue Ridge Mountains, and theMississippi Riverforms its western boundary.[183]Due to flooding of the Mississippi that has changed its path, the state's western boundary deviates from the river in some places.[184]The northern border was originally defined as36°30′ north latitudeand theRoyal Colonial Boundary of 1665, but due to faulty surveys, begins north of this line in the east, and to the west, gradually veers north before shifting south onto the actual 36°30′ parallel at the Tennessee River in West Tennessee.[183][185]Uncertainties in the latter 19th century over the location of the state's border with Virginia culminated in the U.S. Supreme Courtsettling the matter in 1893, which resulted in the division ofBristolbetween the two states.[186]An 1818 survey erroneously placed Tennessee's southern border 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the35th parallel; Georgia legislatorscontinue to dispute this placement, as it prevents Georgia from accessing the Tennessee River.[187]

Marked by a diversity of landforms and topographies, Tennessee features six principalphysiographic provinces, from east to west, which are part of three larger regions: theBlue Ridge Mountains,Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, andCumberland Plateau, part of theAppalachian Mountains; theHighland RimandNashville Basin, part of theInterior Low Plateausof theInterior Plains; and theEast Gulf Coastal Plain, part of theAtlantic Plains.[188][189]Other regions include the southern tip of theCumberland Mountains, theWestern Tennessee Valley, and theMississippi Alluvial Plain. The state's highest point, which is also the third-highest peak in eastern North America, isClingmans Dome, at 6,643 feet (2,025 m) above sea level.[190]Its lowest point, 178 feet (54 m), is on the Mississippi River at the Mississippi state line in Memphis.[5]Tennessee has the most caves in the United States, with more than 10,000 documented.[191]

Geological formations in Tennessee largely correspond with the state's topographic features, and, in general, decrease in age from east to west. The state's oldest rocks areigneousstrata more than 1 billion years old found in the Blue Ridge Mountains,[192][193]and the youngest deposits in Tennessee are sands and silts in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain and river valleys that drain into the Mississippi River.[194]Tennessee is considered seismically active and contains two major seismic zones, although destructive earthquakes rarely occur there.[195][196]TheEastern Tennessee Seismic Zonespans the entirety of East Tennessee from northwestern Alabama to southwestern Virginia, and is considered one of the most active zones in the Southeastern United States, frequently producing low-magnitude earthquakes.[197]TheNew Madrid Seismic Zonein the northwestern part of the state produceda series of devastating earthquakesbetween December 1811 and February 1812 that formedReelfoot LakenearTiptonville.[198]

Topography

The southwesternBlue Ridge Mountainslie within Tennessee's eastern edge, and are divided into several subranges, namely theGreat Smoky Mountains,Bald Mountains,Unicoi Mountains,Unaka Mountains, andIron Mountains. These mountains, which average 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea level in Tennessee, contain some of the highest elevations in eastern North America. The state's border with North Carolina roughly follows the highest peaks of this range, including Clingmans Dome. Most of the Blue Ridge area is protected by theCherokee National Forest, theGreat Smoky Mountains National Park, and several federal wilderness areas and state parks.[199]TheAppalachian Trailroughly follows the North Carolina state line before shifting westward into Tennessee.[200]

Stretching west from the Blue Ridge Mountains for about 55 miles (89 km) are theRidge-and-Valley Appalachians, also known as the Tennessee Valley[c]or Great Valley of East Tennessee. This area consists of linear parallel ridges separated by valleys that trend northeast to southwest, the general direction of the entire Appalachian range.[201]Most of these ridges are low, but some of the higher ones are commonly called mountains.[201]Numerous tributaries join to form the Tennessee River in the Ridge and Valley region.[202]

TheCumberland Plateaurises to the west of the Tennessee Valley, with an average elevation of 2,000 feet (610 m).[203]This landform is part of the largerAppalachian Plateauand consists mostly of flat-toppedtablelands.[204]The plateau's eastern edge is relatively distinct, but the westernescarpmentis irregular, containing several long, crooked stream valleys separated by rocky cliffs with numerouswaterfalls.[205]TheCumberland Mountains, with peaks above 3,500 feet (1,100 m), comprise the northeastern part of the Appalachian Plateau in Tennessee, and the southeastern part of the Cumberland Plateau is divided by theSequatchie Valley.[205]TheCumberland Trailtraverses the eastern escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains.[206]

West of the Cumberland Plateau is theHighland Rim, an elevated plain that surrounds theNashville Basin, ageological dome.[207]Both of these physiographic provinces are part of theInterior Low Plateausof the largerInterior Plains. The Highland Rim is Tennessee's largest geographic region, and is often split into eastern and western halves.[208]The Eastern Highland Rim is characterized by relatively level plains dotted by rolling hills, and the Western Highland Rim and western Nashville Basin are covered with uneven rounded knobs with steepravinesseparated by meandering streams.[209]The Nashville Basin has rich, fertile farmland,[210]and porous limestone bedrock very close to the surface underlies both the Nashville Basin and Eastern Highland Rim.[211]This results inkarstthat forms numerous caves, sinkholes, depressions, and underground streams.[212]

West of the Highland Rim is theWestern Tennessee Valley, which consists of about 10 miles (16 km) in width of hilly land along the banks of the Tennessee River.[213]West of this is theGulf Coastal Plain, a broad feature that begins at theGulf of Mexicoand extends northward into southernIllinois.[214]The plain begins in the east with low rolling hills and wide stream valleys, known as the West Tennessee Highlands, and gradually levels out to the west.[215]It ends at steeploessbluffs overlooking theMississippi embayment, the westernmost physiographic division of Tennessee, which is part of the largerMississippi Alluvial Plain.[216]This flat 10 to 14 miles (16 to 23 km) wide strip is commonly known as the Mississippi Bottoms, and contains lowlands,floodplains, andswamps.[217][218]

Hydrology

Tennessee is drained bythree major rivers, theTennessee,Cumberland, andMississippi. The Tennessee River begins at the juncture of theHolstonandFrench Broadrivers in Knoxville, flows southwest to Chattanooga, and exits into Alabama before reemerging in the western part of the state and flowing north into Kentucky.[219]Its major tributaries include theClinch,Little Tennessee,Hiwassee,Sequatchie,Elk,Beech,Buffalo,Duck, andBig Sandyrivers.[219]The Cumberland River flows through the north-central part of the state, emerging in the northeastern Highland Rim, passing through Nashville, turning northwest to Clarksville, and entering Kentucky east of the Tennessee River.[220]Its principal branches in Tennessee are theObey,Caney Fork,Stones,Harpeth, andRedrivers.[220]The Mississippi River drains nearly all of West Tennessee.[221]Its tributaries are theObion,Forked Deer,Hatchie,Loosahatchie, andWolfrivers.[221]TheTennessee Valley Authority(TVA) and theU.S. Army Corps of Engineersoperate many hydroelectric dams on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers and their tributaries, which form large reservoirs throughout the state.[222]

About half the state's land area is in theTennessee Valleydrainage basin of the Tennessee River.[219]The Cumberland River basin covers the northern half of Middle Tennessee and a small portion of East Tennessee.[220]A small part of north-central Tennessee is in theGreen Riverwatershed.[223]All three of these basins are tributaries of theOhio Riverwatershed. Most of West Tennessee is in theLower Mississippi Riverwatershed.[221]The entirety of the state is in theMississippi River watershed, except for a small sliver near the southeastern corner traversed by theConasauga River, which is part of theMobile Baywatershed.[224]

Ecology

Tennessee is within atemperate deciduous forestbiome commonly known as the Eastern Deciduous Forest.[225]It has eightecoregions: theBlue Ridge,Ridge and Valley, Central Appalachian, Southwestern Appalachian,Interior Low Plateaus, Southeastern Plains, Mississippi Valley Loess Plains, andMississippi Alluvial Plainregions.[226]Tennessee is the mostbiodiverseinland state,[227]the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most biodiverse national park,[228][229]and theDuck Riveris the most biologically diverse waterway in North America.[230]The Nashville Basin is renowned for its diversity of flora and fauna.[231]Tennessee is home to 340 species of birds, 325freshwater fishspecies, 89 mammals, 77 amphibians, and 61 reptiles.[228]

Forests cover about 52% of Tennessee's land area, withoak–hickorythe dominant type.[232]Appalachian oak–pineandcove hardwoodforests are found in the Blue Ridge Mountains and Cumberland Plateau, andbottomland hardwoodforests are common throughout the Gulf Coastal Plain.[233]Pineforests are also found throughout the state.[233]TheSouthern Appalachian spruce–fir forestin the highest elevations of the Blue Ridge Mountains is considered the second-most endangered ecosystem in the country.[234]Some of the last remaining largeAmerican chestnuttrees grow in the Nashville Basin and are being used to help breedblight-resistant trees.[235]Middle Tennessee is home to many unusual and rare ecosystems known ascedar glades, which occur in areas with shallow limestone bedrock that is largely barren of overlying soil and contain many endemic plant species.[236]

Common mammals found throughout Tennessee includewhite-tailed deer,redandgray foxes,coyotes,raccoons,opossums,wild turkeys,rabbits, andsquirrels.Black bearsare found in the Blue Ridge Mountains and on the Cumberland Plateau. Tennessee has the third-highest number of amphibian species, with the Great Smoky Mountains home to the mostsalamanderspecies in the world.[237]The state ranks second in the nation for the diversity of its freshwater fish species.[238]

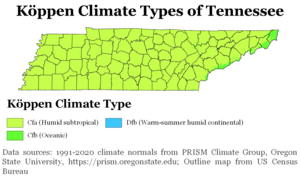

Climate

Most of Tennessee has ahumid subtropical climate, with the exception of some of the higher elevations in the Appalachians, which are classified as a coolermountain temperateorhumid continental climate.[239]TheGulf of Mexicois the dominant factor in Tennessee's climate, with winds from the south responsible for most of the state's annual precipitation. Generally, the state has hot summers and mild to cool winters with generous precipitation throughout the year. The highest average monthly precipitation usually occurs between December and April. The driest months, on average, are August to October. The state receives an average of 50 inches (130 cm) of precipitation annually. Snowfall ranges from 5 inches (13 cm) in West Tennessee to over 80 inches (200 cm) in East Tennessee's highest mountains.[240][241]

Summers are generally hot and humid, with most of the state averaging a high of around 90 °F (32 °C). Winters tend to be mild to cool, decreasing in temperature at higher elevations. For areas outside the highest mountains, the average overnight lows are generally near freezing. The highest recorded temperature was 113 °F (45 °C) atPerryvilleon August 9, 1930, while the lowest recorded temperature was −32 °F (−36 °C) atMountain Cityon December 30, 1917.[242]

While Tennessee is far enough from the coast to avoid any direct impact from a hurricane, its location makes it susceptible to the remnants of tropicalcyclones, which weaken over land and can cause significant rainfall.[243]The state annually averages about 50 days of thunderstorms, which can be severe with large hail and damaging winds.[244]Tornadoes are possible throughout the state, with West and Middle Tennessee the most vulnerable. The state averages 15 tornadoes annually.[245]They can be severe, and the state leads the nation in the percentage of total tornadoes that have fatalities.[246]Winter storms such as in1993and2021occur occasionally, andice stormsare fairly common. Fog is a persistent problem in some areas, especially in East Tennessee.[247]

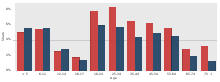

| Monthly Normal High and Low Temperatures For Various Tennessee Cities (F)[248] | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | 44/25 | 49/27 | 57/34 | 66/41 | 74/51 | 81/60 | 85/64 | 84/62 | 79/56 | 68/43 | 58/35 | 48/27 |

| Chattanooga | 50/31 | 54/33 | 63/40 | 72/47 | 79/56 | 86/65 | 90/69 | 89/68 | 82/62 | 72/48 | 61/40 | 52/33 |

| Knoxville | 47/30 | 52/33 | 61/40 | 71/48 | 78/57 | 85/65 | 88/69 | 87/68 | 81/62 | 71/50 | 60/41 | 50/34 |

| Memphis | 50/31 | 55/36 | 63/44 | 72/52 | 80/61 | 89/69 | 92/73 | 92/72 | 86/65 | 75/52 | 62/43 | 52/34 |

| Nashville | 47/28 | 52/31 | 61/39 | 70/47 | 78/57 | 85/65 | 89/70 | 89/69 | 82/61 | 71/49 | 59/40 | 49/32 |

Cities, towns, and counties

Tennessee is divided into95 counties, each of which has acounty seat.[249]The state has340 municipalitiesin total.[250]TheOffice of Management and Budgetdesignatesten metropolitan areasin Tennessee, four of which extend into neighboring states.[251]

Nashville is Tennessee's capital and largest city, with nearly 700,000 residents.[252]Its13-county metropolitan areahas been the state's largest since the early 1990s and is one of the nation's fastest-growing metropolitan areas, with about 2 million residents.[253]Memphis, with more than 630,000 inhabitants, was the state's largest city until 2016, when Nashville surpassed it.[2]It is inShelby County, Tennessee's largest county in both population and land area.[254]Knoxville, with about 190,000 inhabitants, andChattanooga, with about 180,000 residents, are the third- and fourth-largest cities, respectively.[252]Clarksvilleis a significant population center, with about 170,000 residents.[252]Murfreesborois the sixth-largest city and Nashville's largestsuburb, with more than 150,000 residents.[252]In addition to the major cities, theTri-CitiesofKingsport,Bristol, andJohnson Cityare considered the sixth major population center.[255]

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nashville  Memphis |

1 | Nashville | Davidson | 689,447 |  Knoxville Chattanooga |

||||

| 2 | Memphis | Shelby | 633,104 | ||||||

| 3 | Knoxville | Knox | 190,740 | ||||||

| 4 | Chattanooga | Hamilton | 181,099 | ||||||

| 5 | Clarksville | Montgomery | 166,722 | ||||||

| 6 | Murfreesboro | Rutherford | 152,769 | ||||||

| 7 | Franklin | Williamson | 83,454 | ||||||

| 8 | Johnson City | Washington | 71,046 | ||||||

| 9 | Jackson | Madison | 68,205 | ||||||

| 10 | Hendersonville | Sumner | 61,753 | ||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 35,691 | — | |

| 1800 | 105,602 | 195.9% | |

| 1810 | 261,727 | 147.8% | |

| 1820 | 422,823 | 61.6% | |

| 1830 | 681,904 | 61.3% | |

| 1840 | 829,210 | 21.6% | |

| 1850 | 1,002,717 | 20.9% | |

| 1860 | 1,109,801 | 10.7% | |

| 1870 | 1,258,520 | 13.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,542,359 | 22.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,767,518 | 14.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,020,616 | 14.3% | |

| 1910 | 2,184,789 | 8.1% | |

| 1920 | 2,337,885 | 7.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,616,556 | 11.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,915,841 | 11.4% | |

| 1950 | 3,291,718 | 12.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,567,089 | 8.4% | |

| 1970 | 3,923,687 | 10.0% | |

| 1980 | 4,591,120 | 17.0% | |

| 1990 | 4,877,185 | 6.2% | |

| 2000 | 5,689,283 | 16.7% | |

| 2010 | 6,346,105 | 11.5% | |

| 2020 | 6,910,840 | 8.9% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 7,126,489 | 3.1% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[256] | |||

The2020 United States censusreported Tennessee's population at 6,910,840, an increase of 564,735, or 8.90%, since the2010 census.[4]Between 2010 and 2019, the state received a natural increase of 143,253 (744,274 births minus 601,021 deaths), and an increase from net migration of 338,428 people into the state.Immigrationfrom outside the U.S. resulted in a net increase of 79,086, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 259,342.[257]Tennessee'scenter of populationis inMurfreesboroinRutherford County.[258]

According to the 2020 census, 5.7% of Tennessee's population were under age5, 22.1% were under 18, and 17.1% were 65 or older.[259]In recent years, Tennessee has been a top source of domestic migration, receiving an influx of people relocating from places such asCalifornia, theNortheast, and theMidwestdue to the low cost of living and booming employment opportunities.[260][261]In 2019, about 5.5% of Tennessee's population was foreign-born. Of the foreign-born population, approximately 42.7% were naturalized citizens and 57.3% non-citizens.[262]The foreign-born population consisted of approximately 49.9% fromLatin America, 27.1% fromAsia, 11.9% fromEurope, 7.7% fromAfrica, 2.7% fromNorthern America, and 0.6% fromOceania.[263]In 2018, The top countries of origin for Tennessee's immigrants wereMexico,India,Honduras,ChinaandEgypt.[264]

With the exception of a slump in the 1980s, Tennessee has been one of the fastest-growing states in the nation since 1970, benefiting from the largerSun Beltphenomenon.[265]The state has been a top destination for people relocating fromNortheasternandMidwesternstates. This time period has seen the birth of new economic sectors in the state and has positioned the Nashville and Clarksville metropolitan areas as two of the fastest-growing regions in the country.[266]

According toHUD's 2022Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 10,567homelesspeople in Tennessee.[267][268]

Ethnicity

| Race and Ethnicity[269] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 70.9% | 74.6% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 15.7% | 17.0% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[d] | — | 6.9% | ||

| Asian | 1.9% | 2.5% | ||

| Native American | 0.2% | 2.0% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.1% | 0.3% | ||

-

Non-Hispanic White 50–60%60–70%70–80%80–90%90%+Black or African American 50–60%

| Historical racial composition | 1940[270] | 1970[270] | 1990[270] | 2000[e][271] | 2010[271] | 2020[259] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 82.5% | 83.9% | 83.0% | 80.2% | 77.6% | 72.2% |

| Black | 17.4% | 15.8% | 16.0% | 16.4% | 16.7% | 15.8% |

| Asian | - | 0.1% | 0.7% | 1.0% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

| Native | - | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| Native Hawaiianand other Pacific Islander |

- | - | – | – | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Other race | - | - | 0.2% | 1.0% | 2.2% | 3.6% |

| Two or more races | - | - | – | 1.1% | 1.7% | 6.0% |

In 2020, 6.9% of the total population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race), up from 4.6% in 2010. Between 2000 and 2010, Tennessee's Hispanic population grew by 134.2%, the third-highest rate of any state.[272]In 2020,Non-Hispanic or Latino Whiteswere 70.9% of the population, compared to 57.7% of the population nationwide.[273]In 2010, the five most common self-reported ethnic groups in the state wereAmerican(26.5%),English(8.2%),Irish(6.6%),German(5.5%), andScotch-Irish(2.7%).[274]Most Tennesseans who self-identify as havingAmerican ancestryare ofEnglishandScotch-Irishancestry. An estimated 21–24% of Tennesseans are of predominantlyEnglishancestry.[275][276]

Religion

Since colonization, Tennessee has always been predominantlyChristian. About 81% of the population identifies as Christian, withProtestantsmaking up 73% of the population. Of the Protestants in the state,Evangelical Protestantscompose 52% of the population,Mainline Protestants13%, andHistorically Black Protestants8%.Roman Catholicsmake up 6%,Mormons1%, andOrthodox Christiansless than 1%.[277]The largest denominations by number of adherents are theSouthern Baptist Convention, theUnited Methodist Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and theChurches of Christ.[278]MuslimsandJewseach make up about 1% of the population, and adherents of other religions make up about 3% of the population. About 14% of Tennesseans arenon-religious, with 11% identifying as "Nothing in particular", 3% asagnostics, and 1% asatheists.[277]

Tennessee is included in most definitions of theBible Belt, and is ranked asone of the nation's most religious states.[279]Several Protestant denominations have their headquarters in Tennessee, including theSouthern Baptist ConventionandNational Baptist Convention(in Nashville); theChurch of God in Christand theCumberland Presbyterian Church(in Memphis);[280]and theChurch of Godand theChurch of God of Prophecy(inCleveland);[281][282]and theNational Association of Free Will Baptists(inAntioch).[283]Nashville has publishing houses of several denominations.[284]

Economy

As of 2021, Tennessee had agross state productof $418.3 billion.[285]In 2020, the state'sper capita personal incomewas $30,869. Themedian household incomewas $54,833.[262]About 13.6% percent of the population was below thepoverty line.[4]In 2019, the state reported a total employment of 2,724,545 and a total number of 139,760 employer establishments.[4]Tennessee is aright-to-workstate, like most of its Southern neighbors.[286]Unionizationhas historically been low and continues to decline, as in most of the U.S.[287]

Taxation

Tennessee has a reputation as a low-tax state and is usually ranked as one of the five states with the lowest tax burden on residents.[288]Despite being low-tax, it is ranked third among U.S. states for fiscal health.[289]It is one of nine states that do not have ageneral income tax; thesales taxis the primary means of funding the government.[290]TheHall income taxwas imposed on mostdividendsandinterestat a rate of 6% but was completely phased out by 2021.[291]The first $1,250 of individual income and $2,500 of joint income was exempt from this tax.[292]Property taxesare the primary source of revenue for local governments.[293]

The state's sales anduse taxrate for most items is 7%, the second-highest in the nation, along with Mississippi, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Indiana. Food is taxed at 4%, but candy, dietary supplements, and prepared foods are taxed at 7%.[294]Local sales taxes are collected in most jurisdictions at rates varying from 1.5% to 2.75%, bringing the total sales tax between 8.5% and 9.75%. The average combined rate is about 9.5%, the nation's highest average sales tax.[295]Intangible propertytax is assessed on the shares of stockholders of any loan, investment, insurance, or for-profit cemetery companies. The assessment ratio is 40% of the value times the jurisdiction's tax rate.[293]Since 2016, Tennessee has had no inheritance tax.[296]

Agriculture

Tennessee has theeighth-most farms in the nation, which cover more than 40% of its land area and have an average size of about 155 acres (0.63 km2).[297]Cash receipts for crops and livestock have an estimated annual value of $3.5 billion, and the agriculture sector has an estimated annual impact of $81 billion on the state's economy.[297]Beef cattleis the state's largest agricultural commodity, followed bybroilersandpoultry.[17]Tennessee ranks 12th in the nation for the number of cattle, with more than half of its farmland dedicated to cattle grazing.[297][298]Soybeansandcornare the state's first and second-most common crops, respectively,[17]and are most heavily grown in West and Middle Tennessee, especially the northwestern corner of the state.[299][300]Tennessee ranks seventh in the nation incottonproduction, most of which is grown in the fertile soils of central West Tennessee.[301]

The state ranks fourth nationwide in the production oftobacco, which is predominantly grown in the Ridge-and-Valley region of East Tennessee.[302]Tennessee farmers are also known worldwide for their cultivation oftomatoesandhorticulturalplants.[303][304]Other important cash crops in the state includehay,wheat,eggs, andsnap beans.[297][302]The Nashville Basin is a top equestrian region, due to soils that produce grass favored by horses. TheTennessee Walking Horse, first bred in the region in the late 18th century, is one of the world's most recognized horse breeds.[305]Tennessee also ranks second nationwide formulebreeding and the production ofgoat meat.[302]The state's timber industry is largely concentrated on the Cumberland Plateau and ranks as one of the top producers ofhardwoodnationwide.[306]

Industry

UntilWorld War II, Tennessee, like most Southern states, remained predominantly agrarian. Chattanooga became one of the first industrial cities in the south in the decades after theCivil War, when many factories, including iron foundries, steel mills, and textile mills were constructed there.[130]But most of Tennessee's industrial growth began with the federal investments in theTennessee Valley Authority(TVA) and theManhattan Projectin the 1930s and 1940s. The state's industrial and manufacturing sector continued to expand in the succeeding decades, and Tennessee is now home to more than 2,400 advanced manufacturing establishments, which produce a total of more than $29 billion worth of goods annually.[307]

Theautomotive industryis Tennessee's largest manufacturing sector and one of the nation's largest.[308]Nissan'sassembly plantinSmyrnais the largest automotive assembly plant in North America.[309]Two other automakers have assembly plants in Tennessee:General MotorsinSpring HillandVolkswageninChattanooga.[310]Fordis constructingan assembly plantinStantonthat is expected to be operational in 2025.[311]In addition, the state contains more than 900 automotive suppliers.[312]Nissan andMitsubishi Motorshave their North American corporate headquarters inFranklin.[313][314]The state is also one of the top producers offood and drink products, its second-largest manufacturing sector.[315]A number of well-known brands originated in Tennessee, and even more are produced there.[316]Tennessee also ranks as one of the largest producers ofchemicals.[315]Chemical products manufactured in Tennessee includeindustrial chemicals,paints,pharmaceuticals,plastic resins, andsoapsandhygiene products. Additional important products manufactured in Tennessee includefabricated metalproducts,electrical equipment,consumer electronicsandelectrical appliances, and nonelectrical machinery.[316]

Business

Tennessee's commercial sectoris dominated by a wide variety of companies, but its largest service industries include health care, transportation, music and entertainment, banking, and finance. Large corporations with headquarters in Tennessee includeFedEx,AutoZone,International Paper, andFirst Horizon Corporation, all based in Memphis;Pilot CorporationandRegal Entertainment Groupin Knoxville;Hospital Corporation of Americabased in Nashville;Unumin Chattanooga; Acadia Senior Living andCommunity Health Systemsin Franklin; Eastman Chemical headquartered in Kingsport;Dollar Generalin Goodlettsville, and LifePoint Health,Tractor Supply Company, andDelek USin Brentwood.[317][318]

Since the 1990s, the geographical area between Oak Ridge and Knoxville has been known as the Tennessee Technology Corridor, with more than 500 high-tech firms in the region.[319]Theresearch and developmentindustry in Tennessee is also one of the largest employment sectors, mainly due to the prominence ofOak Ridge National Laboratory(ORNL) and theY-12 National Security Complexin the city ofOak Ridge. ORNL conducts scientific research inmaterials science,nuclear physics, energy,high-performance computing,systems biology, andnational security, and is the largestnational laboratoryin theDepartment of Energy(DOE) system by size.[157][320]The technology sector is also a rapidly growing industry in Middle Tennessee, particularly in the Nashville metropolitan area.[321]

Energy and mineral production

Tennessee's electric utilities are regulated monopolies, as in many other states.[322][323]TheTennessee Valley Authority(TVA) owns over 90% of the state's generating capacity.[324]Nuclear poweris Tennessee's largest source of electricity generation, producing about 43.4% of its power in 2021. The same year, 22.4% of the power was produced fromcoal, 17.8% fromnatural gas, 15.8% fromhydroelectricity, and 1.3% from otherrenewables. About 59.7% of the electricity generated in Tennessee producesno greenhouse gas emissions.[325]Tennessee is home to the firstnuclear power reactorin the U.S. to begin operation in the 21st century, which is at theWatts Bar Nuclear PlantinRhea County.[326]Tennessee was also an early leader in hydroelectric power,[327]and today is the third-largest hydroelectric power-producing state east of theRocky Mountains.[328]Tennessee is a net consumer of electricity, receiving power from other TVA facilities in neighboring states.[329]

Tennessee has very little petroleum and natural gas reserves, but is home to one oil refinery, in Memphis.[328]Bituminous coalis mined in small quantities in the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains.[330]There are sizable reserves oflignite coalin West Tennessee that remain untapped.[330]Coal production in Tennessee peaked in 1972, and today less than 0.1% of coal in the U.S. comes from Tennessee.[328]Tennessee is the nation's leading producer ofball clay.[330]Other major mineral products produced in Tennessee includesand,gravel,crushed stone,Portland cement,marble,sandstone,common clay,lime, andzinc.[330][331]TheCopper Basin, in Tennessee's southeastern corner in Polk County, was one of the nation's most productivecopper miningdistricts between the 1840s and 1980s, and supplied about 90% of the copper the Confederacy used during the Civil War.[332]Mining activities in the basin resulted in a major environmental disaster, which left the surrounding landscape barren for more than a century.[333]Iron ore was another major mineral mined in Tennessee until the early 20th century.[334]Tennessee was also a top producer ofphosphateuntil the early 1990s.[335]

Tourism

Tennessee is the 11th-most visited state in the nation,[337]receiving a record of 126 million tourists in 2019.[338]Its top tourist attraction is theGreat Smoky Mountains National Park, the most visited national park in the U.S., with more than 14 million visitors annually.[336]The park anchors a large tourism industry based primarily in nearbyGatlinburgandPigeon Forge, which includesDollywood, the most visited ticketed attraction in Tennessee.[339]Attractions related to Tennessee's musical heritage are spread throughout the state.[340][341]Other top attractions include theTennessee State MuseumandParthenonin Nashville; theNational Civil Rights MuseumandGracelandin Memphis;Lookout Mountain, theChattanooga Choo-Choo Hotel,Ruby Falls, and theTennessee Aquariumin Chattanooga; theAmerican Museum of Science and Energyin Oak Ridge, theBristol Motor Speedway,Jack Daniel's Distilleryin Lynchburg, and theHiwasseeandOcoeerivers in Polk County.[339]

TheNational Park Servicepreserves four Civil War battlefields in Tennessee:Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park,Stones River National Battlefield,Shiloh National Military Park, andFort Donelson National Battlefield.[342]The NPS also operatesBig South Fork National River and Recreation Area,Cumberland Gap National Historical Park,Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail,Trail of Tears National Historic Trail,Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, and theManhattan Project National Historical Park.[343]Tennessee is home to eightNational Scenic Byways, including theNatchez Trace Parkway, theEast Tennessee Crossing Byway, theGreat River Road, theNorris Freeway,Cumberland National Scenic Byway,Sequatchie Valley Scenic Byway,The Trace, and theCherohala Skyway.[344][345]Tennessee maintains 56 state parks, covering 132,000 acres (530 km2).[346]Many reservoirs created by TVA dams have also generated water-based tourist attractions.[347]

Culture

Tennessee blends southernAppalachianandSouthernflavors, which originate from its English, Scotch-Irish, and African roots, and has evolved as it has grown. ItsGrand Divisionsalso manifest into distinct cultural regions, with East Tennessee commonly associated with Southern Appalachia,[348]and Middle and West Tennessee commonly associated withUpland Southern cultureand sometimes evenDeep Southernculture.[349]Parts of West Tennessee, especially Memphis, are sometimes considered part of theDeep South. Some areas of the state, most notably Nashville, are also known for their since ofrodeoculture as well. Nashville is also nicknamed “The Home ofCountry Music”.[350]TheTennessee State Museumin Nashville chronicles the state's history and culture.[351]

Tennessee is perhaps best known culturally for its musical heritage and contributions to the development of many forms ofpopular music, particularly in the country genre.[352][353]Notable authors with ties to Tennessee includeCormac McCarthy,Peter Taylor,James Agee,Francis Hodgson Burnett,Thomas S. Stribling,Ida B. Wells,Nikki Giovanni,Shelby Foote,Ann Patchett,Ishmael Reed, andRandall Jarrell. The state's well-known contributions toSouthern cuisineincludeMemphis-style barbecue,Nashville hot chicken, andTennessee whiskey.[354]

Music

Tennessee has played a critical role in the development of many forms of American popular music, includingblues,country,rock and roll,rockabilly,soul,bluegrass,Contemporary Christian, andgospel. Many consider Memphis'sBeale Streetthe epicenter of the blues, with musicians such asW. C. Handyperforming in its clubs as early as 1909.[352]Memphis was historically home toSun Records, where musicians such asElvis Presley,Johnny Cash,Carl Perkins,Jerry Lee Lewis,Roy Orbison, andCharlie Richbegan their recording careers, and where rock and roll took shape in the 1950s.[352]Stax Recordsin Memphis became one of the most important labels for soul artists in the late 1950s and 1960s, and a subgenre known asMemphis soulemerged.[355]The1927 Victor recording sessionsinBristolgenerally mark the beginning of the country music genre and the rise of theGrand Ole Opryin the 1930s helped make Nashville the center of the country music recording industry.[356][357]Nashville became known as "Music City", and theGrand Ole Opryremains the nation's longest-running radio show.[353]

Many museums and historic sites recognize Tennessee's role in nurturing various forms of popular music, includingSun Studio,Memphis Rock N' Soul Museum,Stax Museum of American Soul Music, andBlues Hall of Famein Memphis, theRyman Auditorium,Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum,Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum,National Museum of African American Music, andMusic Rowin Nashville, the International Rock-A-Billy Museum in Jackson, theMountain Music Museumin Kingsport, and theBirthplace of Country Music Museumin Bristol.[358]TheRockabilly Hall of Fame, an online site recognizing the development of rockabilly, is also based in Nashville. Several annual music festivals take place throughout the state, the largest of which are theBeale Street Music Festivalin Memphis, theCMA Music Festivalin Nashville,BonnarooinManchester, andRiverbendin Chattanooga.[359]

Education

Education in Tennessee is administered by the Tennessee Department of Education.[360]The state Board of Education has 11 members: one from each Congressional district, a student member, and the executive director of theTennessee Higher Education Commission(THEC), who serves as ex-officio nonvoting member.[361]Public primary and secondary education systems are operated by county, city, or special school districts to provide education at the local level, and operate under the direction of the Tennessee Department of Education.[360]The state also has many private schools.[362]

The state enrolls approximately 1 millionK–12students in 137 districts.[363]In 2021, the four-year high school graduation rate was 88.7%, a decrease of 1.2% from the previous year.[364]According to the most recent data, Tennessee spends $9,544 per student, the 8th lowest in the nation.[365]

Colleges and universities

Public higher education is overseen by theTennessee Higher Education Commission(THEC), which provides guidance to the state's two public university systems. TheUniversity of Tennessee systemoperates four primary campuses inKnoxville,Chattanooga,Martin, andPulaski; aHealth Sciences Centerin Memphis; and anaerospace research facilityin Tullahoma.[366]TheTennessee Board of Regents(TBR), also known as The College System of Tennessee, operates 13 community colleges and 27 campuses of theTennessee Colleges of Applied Technology(TCAT).[367]Until 2017, the TBR also operated six public universities in the state; it now only gives them administrative support.[368]

In 2014, the Tennessee General Assembly created theTennessee Promise, which allows in-state high school graduates to enroll in two-year post-secondary education programs such as associate degrees and certificates at community colleges andtrade schoolsin Tennessee tuition-free, funded by the state lottery, if they meet certain requirements.[369]The Tennessee Promise was created as part of then-governorBill Haslam's "Drive to 55" program, which set a goal of increasing the number of college-educated residents to at least 55% of the state's population.[369]The program has also received national attention, with multiple states having since created similar programs modeled on the Tennessee Promise.[370]

Tennessee has 107 private institutions.[371]Vanderbilt Universityin Nashville is consistently ranked as one of the nation's leading research institutions.[372]Nashville is often called the "Athens of the South" due to its many colleges and universities.[373]Tennessee is also home to sixhistorically Black colleges and universities(HBCUs).[374]

Media

Tennessee is home to more than 120 newspapers. The most-circulated paid newspapers in the state includeThe Tennesseanin Nashville,The Commercial Appealin Memphis, theKnoxville News Sentinel, theChattanooga Times Free Press, andThe Leaf-Chroniclein Clarksville,The Jackson Sun, andThe Daily News Journalin Murfreesboro. All of these except theTimes Free Pressare owned byGannett.[375]

Sixtelevision media markets—Nashville, Memphis, Knoxville, Chattanooga, Tri-Cities, and Jackson—are based in Tennessee. The Nashville market is the third-largest in theUpland Southand the ninth-largest in the southeastern United States, according toNielsen Media Research. Small sections of the Huntsville, Alabama andPaducah, Kentucky-Cape Girardeau, Missouri-Harrisburg, Illinoismarkets also extend into the state.[376]Tennessee has 43 full-power and 41low-powertelevision stations[377]and more than 450Federal Communications Commission(FCC)-licensed radio stations.[378]TheGrand Ole Opry, based in Nashville, is the longest-running radio show in the country, having broadcast continuously since 1925.[353]

Transportation

TheTennessee Department of Transportation(TDOT) is the primary agency that is tasked with regulating and maintaining Tennessee's transportation infrastructure.[379]Tennessee is currently one of five states with no transportation-related debts.[380][381]

Roads

Tennessee has 96,167 miles (154,766 km) of roads, of which 14,109 miles (22,706 km) are maintained by the state.[382]Of the state's highways, 1,233 miles (1,984 km) are part of theInterstate Highway System. Tennessee has notolledroads or bridges but has the sixth-highest mileage ofhigh-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes, which are utilized on freeways in the congestion-prone Nashville and Memphis metropolitan areas.[383]

Interstate 40(I-40) is the longest Interstate Highway in Tennessee, traversing the state for 455 miles (732 km).[384]Known as "Tennessee's Main Street", I-40 serves the major cities of Memphis, Nashville, and Knoxville, and throughout its entire length in Tennessee, one can observe the diversity of the state's geography and landforms.[203][385]I-40's branch interstates includeI-240in Memphis;I-440in Nashville;I-840around Nashville;I-140from Knoxville toMaryville; andI-640in Knoxville. In a north–south orientation, from west to east, are interstates55, which serves Memphis;65, which passes through Nashville;75, which serves Chattanooga and Knoxville; and81, which begins east of Knoxville, and serves Bristol to the northeast.I-24is an east–west interstate that enters the state in Clarksville, passes through Nashville, and terminates in Chattanooga.I-26, although technically an east–west interstate, begins in Kingsport and runs southwardly throughJohnson Citybefore exiting into North Carolina.I-155is a branch route of I-55 that serves the northwestern part of the state.I-275is a short spur route in Knoxville.I-269runs fromMillingtontoCollierville, serving as an outer bypass of Memphis.[384][386]

Airports

Major airports in Tennessee includeNashville International Airport(BNA),Memphis International Airport(MEM),McGhee Tyson Airport(TYS) outside of Knoxville,Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport(CHA),Tri-Cities Regional Airport(TRI) inBlountville, andMcKellar-Sipes Regional Airport(MKL) in Jackson. Because Memphis International Airport is the hub ofFedEx Corporation, it is theworld's second-busiest cargo airport.[387]The state also has 74general aviationairports and 148heliports.[382]

Railroads

For passenger rail service, Memphis andNewbernare served by theAmtrakCity of New Orleansline on its run betweenChicagoandNew Orleans.[388]Nashville is served by theWeGo Starcommuter railservice.[389]Tennessee currently has 2,604 miles (4,191 km) of freight trackage in operation,[390]most of which are owned byCSX Transportation.[391]Norfolk Southern Railwayalso operates lines in East and southwestern Tennessee.[392]BNSFoperates a majorintermodal facilityin Memphis.

Waterways

Tennessee has a total of 976 miles (1,571 km) ofnavigable waterways, the 11th highest in the nation.[382]These include theMississippi,Tennessee, andCumberlandrivers.[393]Five inland ports are located in the state, including thePort of Memphis, which is the fifth-largest in the United States and the second largest on the Mississippi River.[394]

Law and government

TheConstitution of Tennesseewas adopted in 1870. The state had two previous constitutions. The first was adopted in 1796, the year Tennessee was admitted to the union, and the second in 1834. Since 1826,Nashvillehas been the capital of Tennessee. The capital was previously in three other cities.[395]Knoxvillewas the capital from statehood in 1796 until 1812,[395]except for September 21, 1807, when the legislature met inKingstonfor a day.[396]The capital was relocated to Nashville in 1812, where it remained until it was relocated back to Knoxville in 1817. The next year, the capital was moved toMurfreesboro, where it remained until 1826. Nashville was officially named Tennessee's permanent capital in 1843.[395]

Executive and legislative branches

Like the federal government, Tennessee's government has three branches. The executive branch is led by thegovernor, who holds office for a four-year term and may serve a maximum of two consecutive terms.[397]The governor is the only official elected statewide. The current governor isBill Lee, aRepublican. The governor is supported by 22 cabinet-level departments, most headed by a commissioner the governor appoints. The executive branch also includes several agencies, boards, and commissions, some of which are under the auspices of one of the cabinet-level departments.[398]