Bath, Somerset

| Bath | |

|---|---|

| City | |

|

|

Skyline of Bath city centre with

Bath Abbey

|

|

|

Location within

Somerset

|

|

| Population | 94,092 (2021 Census)[1] |

| Demonym | Bathonian |

| OS grid reference | ST750645 |

| •London | 97 miles (156 km)E |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Bath |

| Postcode district | BA1, BA2 |

| Dialling code | 01225 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Official name | City of Bath |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iv |

| Reference | 428 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11thSession) |

| Area | 2,900 ha |

| Part of | Great Spa Towns of Europe |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii |

| Reference | 1613 |

| Inscription | 2021 (44thSession) |

Bath(RP:/bɑːθ/;[2]local pronunciation:[ba(ː)θ][3]) is a city in theceremonial countyofSomerset,[4]in England, known for and named after itsRoman-built baths. At the 2021 Census, the population was 94,092.[1]Bath is in the valley of theRiver Avon, 97 miles (156 km) west ofLondonand 11 miles (18 km) southeast ofBristol. The city became aUNESCOWorld Heritage Sitein 1987, and was later added to the transnational World Heritage Site known as the "Great Spa Towns of Europe" in 2021. Bath is also the largest city and settlement in Somerset.

The city became aspawith theLatinnameAquae Sulis("the waters ofSulis")c.60 AD when the Romans builtbathsand a temple in the valley of the River Avon, althoughhot springswere known even before then.Bath Abbeywas founded in the 7th century and became a religious centre; the building was rebuilt in the 12th and 16th centuries. In the 17th century, claims were made for the curative properties of water from the springs, and Bath became popular as aspa townin theGeorgian era.Georgian architecture, crafted fromBath stone, includes theRoyal Crescent,Circus,Pump Room, and theAssembly Rooms, whereBeau Nashpresided over the city's social life from 1705 until his death in 1761.

Many of the streets and squares were laid out byJohn Wood, the Elder, and in the 18th century the city became fashionable and the population grew.Jane Austenlived in Bath in the early 19th century. Further building was undertaken in the 19th century and following theBath Blitzin World War II. Bath became part of the county ofAvonin 1974, and, following Avon's abolition in 1996, has been the principal centre ofBath and North East Somerset.

Bath has over 6 million yearly visitors,[5]making itone of ten English cities visited most by overseas tourists.[6][7]Attractions include the spas, canal boat tours, Royal Crescent,Bath Skyline,Parade GardensandRoyal Victoria Parkwhich hostscarnivalsand seasonal events. Shopping areas includeSouthGate shopping centre,the Corridorarcadeand artisan shops atWalcot,Milsom,Stalland York Streets. There are theatres, including theTheatre Royal, as well as several museums including theMuseum of Bath Architecture, theVictoria Art Gallery, theMuseum of East Asian Art, theHerschel Museum of Astronomy,Fashion Museum, and theHolburne Museum. The city has two universities – theUniversity of BathandBath Spa University– withBath Collegeprovidingfurther education. Sporting clubs from the city includeBath RugbyandBath City.

History

[edit]Stone, Bronze, and Iron Ages

[edit]The hills in the locality such asBathampton Downsaw human activity from theMesolithicperiod.[8][9]SeveralBronze Ageround barrowswere opened byJohn Skinnerin the 18th century.[10]Along barrowsite believed to be from theEarly Bronze AgeBeaker peoplewas flattened to make way forRAF Charmy Down.[11][12]Solsbury Hilloverlooking the current city was anIron Agehill fortand the adjacent Bathampton Camp may also have been one.[13][14]

Roman baths and town

[edit]

Archaeological evidence shows that the site of theRoman baths'main spring may have been treated as a shrine by theBritons,[15][16]and was dedicated to the goddessSulis, whom theRomansidentified withMinerva; the name Sulis continued to be used after the Roman invasion, appearing in the town'sRoman name,Aquae Sulis(literally, "the waters of Sulis").[17]Messages to her scratched onto metal, known ascurse tablets, have been recovered from the sacred spring by archaeologists.[18]The tablets were written inLatin, and laid curses on personal enemies. For example, if a citizen had his clothes stolen at the baths, he might write a curse against the suspects on a tablet to be read by the goddess.

A temple was constructed in AD 60–70, and a bathing complex was built up over the next 300 years.[19]Engineers drove oak piles into the mud to provide a stable foundation, and surrounded the spring with an irregular stone chamber lined with lead. In the 2nd century, the spring was enclosed within a woodenbarrel-vaultedstructure that housed thecaldarium(hot bath),tepidarium(warm bath), andfrigidarium(cold bath).[20]

The town was later givendefensive walls, probably in the 3rd century.[21]After the failure of Roman authority in the first decade of the 5th century, the baths fell into disrepair and were eventually lost as a result of rising water levels and silting.[22]

In March 2012, a hoard of 30,000 silver Roman coins, one of the largest discovered in Britain, was unearthed in an archaeological dig. The coins, believed to date from the 3rd century, were found about 150 m (490 ft) from the Roman baths.[23]

Post-Roman and medieval

[edit]

Bath may have been the site of theBattle of Badon(c.500 AD), in whichArthur, the hero of later legends, is said to have defeated theAnglo-Saxons.[24]The town was captured by theWest Saxonsin 577 after theBattle of Deorham;[25]the Anglo-Saxon poemThe Ruinmay describe the appearance of the Roman site about this time.[26]A monastery was founded at an early date – reputedly bySaint Davidalthough more probably in 675 byOsric, King of theHwicce,[27]perhaps using thewalled areaas its precinct.[28][29]Nennius, a 9th-century historian, mentions a "Hot Lake" in the land of the Hwicce along theRiver Severn, and adds "It is surrounded by a wall, made of brick and stone, and men may go there to bathe at any time, and every man can have the kind of bath he likes. If he wants, it will be a cold bath; and if he wants a hot bath, it will be hot".Bededescribed hot baths in the geographical introduction to theEcclesiastical Historyin terms very similar to those of Nennius.[30]King OffaofMerciagained control of the monastery in 781 and rebuilt the church, which was dedicated toSt. Peter.[31]

According to the Victorian churchmanEdward Churton, during the Anglo-Saxon era Bath was known asAcemannesceastre('Akemanchester'), or 'aching men's city', on account of the reputation these springs had for healing the sick.[32]

By the 9th century, the old Roman street pattern was lost and Bath was a royal possession.King Alfredlaid out the town afresh, leaving its south-eastern quadrant as the abbey precinct.[21]In theBurghal Hidage, Bath is recorded as aburh(borough) and is described as having walls of 1,375 yards (1,257 m) and was allocated 1000 men for defence.[33]During the reign ofEdward the Eldercoins weremintedin Bath based on a design from theWinchestermint but with 'BAD' on the obverse relating to the Anglo-Saxon name for the town, Baðum, Baðan or Baðon, meaning "at the baths",[34]and this was the source of the present name.Edgar of Englandwas crowned king of England inBath Abbeyin 973, in a ceremony that formed the basis of all futureEnglish coronations.[35]

William Rufusgranted the town, abbey and mint to a royal physician,John of Tours, who became Bishop ofWellsand Abbot of Bath,[36][37]following the sacking of the town during theRebellion of 1088.[38]It was papal policy for bishops to move to more urban seats, and John of Tourstranslatedhis own from Wells to Bath.[39]The bishop planned and began a much larger church as his cathedral, to which was attached a priory, with the bishop's palace beside it.[40]New baths were built around the three springs. Later bishops returned the episcopal seat to Wells while retaining the name Bath in the title,Bishop of Bath and Wells.St John's Hospitalwas founded around 1180 by BishopReginald Fitz Jocelinand is among the oldestalmshousesin England.[41]The 'hospital of the baths' was built beside the hot springs of theCross Bath, for their health-giving properties and to provide shelter for the poor infirm.[42]

Administrative systems fell within thehundreds. TheBath Hundredhad various names including the Hundred of Le Buri. The Bath Foreign Hundred or Forinsecum covered the area outside the city and was later combined into the Bath Forum Hundred. Wealthy merchants had no status within the hundred courts and formedguildsto gain influence. They built the firstguildhallprobably in the 13th century. Around 1200, thefirst mayorwas appointed.[43]

Early modern

[edit]

By the 15th century, Bath's abbey church was dilapidated[44]andOliver King, Bishop of Bath and Wells, decided to rebuild it on a smaller scale in 1500. The new church was completed just a few years before Bath Priory wasdissolvedin 1539 byHenry VIII.[45]The abbey church became derelict before being restored as the city'sparish churchin theElizabethan era, when the city experienced a revival as aspa. The baths were improved and the city began to attract the aristocracy. ARoyal chartergranted by QueenElizabeth Iin 1590 confirmedcity status.[46]James Montagu, Bishop of Bath and Wells from 1608, spent considerable sums in restoring Bath Abbey and actively supported the Baths themselves, aware that the ‘towne liveth wholly by them’. In 1613, perhaps at his behest, Queen Anne visited the town to take the waters: the Queen’s Bath was named after her. The cue for the visit may have been the completion of the restoration work to Bath Abbey, the last instalment of which had been paid for two years previously.[47]Anne of Denmarkcame to Bath in 1613 and 1615.[48]

During theEnglish Civil War, the city was garrisoned forCharles I. Seven thousand pounds was spent on fortifications, but on the appearance of parliamentary forces the gates were thrown open and the city surrendered. It became a significant post for the Western Association army underWilliam Waller.[49]Bath was retaken by the royalists in July 1643 following theBattle of Lansdowneand occupied for two years until 1645.[50][51]Luckily, the city was spared the destruction of property and starvation of its inhabitants unlike nearby Bristol andGloucester. During the occupation, the finances of the Bath City Council took a drubbing with council spending, rents and grants all falling. The billeting of soldiers in private houses also contributed to disorder and vandalism.[51]

Normality to the city quickly recovered after the war when the city council achieved a healthy budget surplus.[51]Thomas Guidott, a student of chemistry and medicine atWadham College, Oxford, set up a practice in the city in 1668. He was interested in the curative properties of the waters, and he wroteA discourse of Bathe, and the hot waters there. Also, Some Enquiries into the Nature of the waterin 1676. It brought the health-giving properties of the hot mineral waters to the attention of the country, and the aristocracy arrived to partake in them.[52]

Several areas of the city were developed in theStuartperiod, and more building took place duringGeorgiantimes in response to the increasing number of visitors who required accommodation.[53]ArchitectsJohn Wood the Elderandhis sonlaid out the new quarters in streets and squares, the identical façades of which gave an impression of palatial scale and classical decorum.[54]Much of the creamy goldBath stone, a type oflimestoneused for construction in the city, was obtained from theCombe Down and Bathampton Down Minesowned byRalph Allen(1694–1764).[55]Allen, to advertise the quality of his quarried limestone, commissioned the elder John Wood to build a country house on hisPrior Parkestate between the city and the mines.[55]Allen was responsible for improving and expanding the postal service in western England, for which he held the contract for more than forty years.[55]Although not fond of politics, Allen was a civic-minded man and a member of Bath Corporation for many years. He was elected mayor for a single term in 1742.[55]

In the early 18th century, Bath acquired its first purpose-built theatre, theOld Orchard Street Theatre. It was rebuilt as theTheatre Royal, along with theGrand Pump Roomattached to the Roman Baths andassembly rooms.Master of ceremoniesBeau Nash, who presided over the city's social life from 1704 until his death in 1761, drew up a code of behaviour for public entertainments.[56]Bath had become perhaps the most fashionable of the rapidly developing British spa towns, attracting many notable visitors such as the wealthy London booksellerAndrew Millarand his wife, who both made long visits.[57]In 1816, it was described as "a seat of amusement and dissipation", where "scenes of extravagance in this receptacle of the wealthy and the idle, the weak and designing" were habitual.[58]

Late modern

[edit]

The population of the city was 40,020 at the 1801 census, making it one of the largest cities in Britain.[59]William Thomas Beckfordbought a house inLansdown Crescentin 1822, and subsequently two adjacent houses to form his residence. Having acquired all the land between his home and the top ofLansdown Hill, he created a garden more than1⁄2mile (800 m) in length and builtBeckford's Towerat the top.[60]

EmperorHaile Selassieof Ethiopia spent four years in exile, from 1936 to 1940, atFairfield Housein Bath.[61]DuringWorld War II, between the evening of 25 April and the early morning of 27 April 1942, Bath suffered three air raids in reprisal forRAFraids on the German cities ofLübeckandRostock, part of theLuftwaffecampaign popularly known as theBaedeker Blitz. During theBath Blitz, more than 400 people were killed, and more than 19,000 buildings damaged or destroyed.[62]

Houses inRoyal Crescent,CircusandParagonwere burnt out along with theAssembly Rooms.[63][64]A 500-kilogram (1,100 lb)high explosivebomb landed on the east side ofQueen Square, resulting in houses on the south side being damaged and theFrancis Hotellosing 24 metres (79 ft) of its frontage.[63]The buildings have all been restored although there are still signs of the bombing.[63][64]

A postwar review of inadequate housing led to the clearance and redevelopment of areas of the city in a postwar style, often at variance with the local Georgian style. In the 1950s, the nearby villages ofCombe Down,TwertonandWestonwere incorporated into the city to enable the development of housing, much of itcouncil housing.[65][66]In 1965, town plannerColin BuchananpublishedBath: A Planning and Transport Study, which to a large degree sought to better accommodate the motor car, including the idea of a traffic tunnel underneath the centre of Bath. Though criticised by conservationists, some parts of the plan were implemented.

In the 1970s and 1980s, it was recognised that conservation of historic buildings was inadequate, leading to more care and reuse of buildings and open spaces.[65][67]In 1987, the city was selected byUNESCOas aWorld Heritage Site, recognising its international cultural significance.[68]

Between 1991 and 2000, Bath was the scene of a series of rapes committed by an unidentified man dubbed the "Batman rapist".[69]The attacker remains at large and is the subject of Britain's longest-running serial rape investigation.[69]He is said to have atightsfetish, have a scar below his bottom lip and resides in the Bath area or knows it very well.[69]He has also been linked to the unsolvedmurder of Melanie Hall, which occurred in the city in 1996.[70]Although the offender's DNA is known and several thousand men in Bath were DNA tested, the attacker continues to evade police.[69]

Since 2000, major developments have included theThermae Bath Spa, theSouthGateshopping centre, the residential Western Riverside project on theStothert & Pittfactory site, and the riverside Bath Quays office and business development.[71][72]In 2021, Bath become part of a second UNESCO World Heritage Site, a group of spa towns across Europe known as the "Great Spas of Europe".[73]This makes it one of the only places to be formally recognised twice as aWorld Heritagesite.[74]

Government

[edit]

Since 1996, the city has had asingle tier of local government—Bath and North East Somerset Council.

Historical development

[edit]Bath had long been anancient borough, having that status since 878 when it became a royal borough (burh) ofAlfred the Great, and was reformed into amunicipal boroughin 1835. It has formed part of thecountyof Somerset since 878, when ceded toWessex, having previously been inMercia(the River Avon had acted as the border between the two kingdoms since 628).[75]However, Bath was made acounty boroughin 1889, independent of the newly createdadministrative countyandSomerset County Council.[76]Bath became part ofAvonwhen thenon-metropolitan countywas created in 1974, resulting in its abolition as a county borough, and instead became a non-metropolitan district withborough status.

With the abolition of Avon in 1996, the non-metropolitan district and borough were abolished too, and Bath has since been part of theunitary authoritydistrict ofBath and North East Somerset(B&NES).[77]The unitary district included also theWansdykedistrict and therefore includes a wider area than the city (the 'North East Somerset' element) includingKeynshamwhich is home to many of the council's offices, though the council meets at theGuildhallin Bath.

Bath was returned to theceremonial countyof Somerset in 1996, though as B&NES is a unitary authority, it is not part of the area covered by Somerset County Council.

Charter trustees

[edit]Bath City Council was abolished in 1996, along with thedistrictof Bath, and there is no longer aparish councilfor the city. The City of Bath's ceremonial functions, including itsformal statusas a city,its twinningarrangements,[78]the mayoralty of Bath– which can be traced back to 1230– and control of the city'scoat of arms, are maintained by thecharter trusteesof the City of Bath.[79]

The councillors elected by the electoral wards that cover Bath (see below) are the trustees, and they elect one of their number as their chair and mayor.[80]The mayor holds office for one municipal year and in modern times the mayor begins their term in office on the first Saturday in June, at a ceremony at Bath Abbey with a civic procession from and to the Guildhall. The 794th mayor, who began her office on 6 May 2021, is June Player. A deputy mayor is also elected.[81]

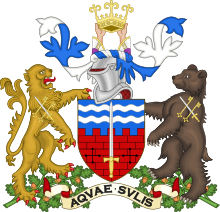

Coat of arms

[edit]The coat of arms includes a depiction of thecity wall, and two silver strips representing theRiver Avonand the hot springs. The sword ofSt. Paulis a link to Bath Abbey. The supporters, a lion and a bear, stand on a bed ofacorns, a link toBladud, the subject of the Legend of Bath. The knight's helmet indicates a municipality and thecrownis that of King Edgar (referencing his coronation at the Abbey).[82]Amural crown, indicating acity, is alternatively used instead of the helmet and Edgar's crown.[83]

The Arms bear the motto "Aqvae Svlis", the Roman name for Bath inLatinscript; although not on the Arms, the motto "Floreat Bathon" is sometimes used ("may Bath flourish" in Latin).

|

|

Bath Area Forum

[edit]Bath and North East Somerset Council has established the Bath City Forum, comprising B&NES councillors representing wards in Bath and up to 13 co-opted members drawn from the communities of the city. The first meeting of the Forum was held on 13 October 2015, at the Guildhall, where the first chair and vice-chair were elected.[85]In 2021, this was re-launched as the Bath Area Forum.[86]

Parliamentary elections

[edit]Bath is one of the oldest extantparliamentary constituenciesin the United Kingdom, being in continuous existence since theModel Parliamentof 1295. Before theReform Act 1832, Bath elected two members to theunreformed House of Commons, as an ancient parliamentary borough.[87]From 1832 until 1918 it elected two MPs and then was reduced to one.

Historically the constituency covered only the city of Bath; however, it was enlarged into some outlying areas between 1997 and 2010. The constituency since 2010 once again covers exactly the city of Bath and is currently represented byLiberal DemocratWera Hobhousewho beatConservativeBen Howlettat the2017 general electionand retained her seat at the2019 general election.Howlett had replaced the retiringLiberal DemocratDon Fosterat the2015 general election. Foster's election was a notable result of the1992 general election, asChris Patten, the previous Member (andCabinet Minister) played a major part, asChairman of the Conservative Party, in re-electing the government ofJohn Major, but failed to defend his marginal seat.[88]

Electoral wards

[edit]The fifteenelectoral wardsof Bath are:Bathwick,Combe Down,Kingsmead, Lambridge,Lansdown, Moorlands,Newbridge,Odd Down, Oldfield Park, Southdown,Twerton,Walcot,Westmoreland,WestonandWidcombe&Lyncombe. These wards are co-extensive with the city, except that Newbridge includes also two parishes beyond the city boundary.[89]

These wards return a total of 28 councillors toBath and North East Somerset Council; all except two wards return two councillors (Moorlands and Oldfield Park return one each). The most recentelections were held on 4 May 2023and all wards returnedLiberal Democratsexcept for Lambridge and Westmoreland which returnedGreen Partyandindependentcouncillors respectively.

Boundary changes enacted from 2 May 2019 included the abolition ofAbbeyward, the merger of Lyncombe and Widcombe wards, the creation of Moorlands ward, and the replacement of Oldfield with Oldfield Park, as well as considerable changes to boundaries affecting all wards.

Geography and environment

[edit]Physical geography

[edit]Bath is in the Avon Valley and is surrounded by limestone hills as it is near the southern edge of theCotswolds, a designatedArea of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and the limestoneMendip Hillsrise around 7 miles (11 km) south of the city. The hills that surround and make up the city have a maximum altitude of 781 feet (238 metres) on the Lansdown plateau. Bath has an area of 11 square miles (28 square kilometres).[90]

Thefloodplainof the Avon has an altitude of about 59 ft (18 m) abovesea level,[91]although the city centre is at an elevation of around 25 metres (82 ft) above sea level.[92]The river, once an unnavigable series ofbraided streamsbroken up byswampsand ponds, has been managed byweirsinto a single channel. Periodic flooding, which shortened the life of many buildings in the lowest part of the city, was normal until major flood control works were completed in the 1970s.[93]Kensington Meadows is an area of mixed woodland and open meadow next to the river which has been designated as alocal nature reserve.[94]

Water bubbling up from the ground asgeothermal springsoriginates as rain on theMendip Hills. The rain percolates through limestone aquifers to a depth of between 9,000 to 14,000 ft (2,700 to 4,300 m) where geothermal energy raises the water's temperature to between 64 and 96 °C (approximately 147–205 °F). Under pressure, the heated water rises to the surface along fissures and faults in the limestone. Hot water at a temperature of 46 °C (115 °F) rises here at the rate of 1,170,000 litres (257,364 imp gal) daily,[95]from the Pennyquickgeological fault.

In 1983, a new spa-water bore-hole was sunk, providing a clean and safe supply for drinking in the Pump Room.[96]There is no universal definition to distinguish ahot springfrom ageothermalspring, although, by severaldefinitions, the Bath springs can be considered the only hot springs in the UK. Three of the springs feed the thermal baths.[97]

Climate

[edit]Along with the rest ofSouth West England, Bath has atemperate climatewhich is generally wetter and milder than the rest of the country.[98]The annual mean temperature is approximately 10 °C (50.0 °F). Seasonal temperature variation is less extreme than most of the United Kingdom because of the adjacent sea temperatures. The summer months of July and August are the warmest, with mean daily maxima of approximately 21 °C (69.8 °F). In winter, mean minimum temperatures of 1 or 2 °C (33.8 or 35.6 °F) are common.[98]In the summer, theAzoreshigh pressure affects the south-west of England bringing fair weather; however,convectivecloud sometimes forms inland, reducing the number of hours of sunshine. Annual sunshine rates are slightly less than the regional average of 1,600 hours.[98]

In December 1998 there were 20 days without sun recorded at Yeovilton. Most of the rainfall in the south-west is caused byAtlantic depressionsor byconvection. Most of the rainfall in autumn and winter is caused by the Atlantic depressions, which is when they are most active. In summer, a large proportion of the rainfall is caused by sun heating the ground, leading to convection and to showers and thunderstorms. Average rainfall is around 700 mm (28 in). About 8–15 days of snowfall is typical. November to March have the highest mean wind speeds, and June to August have the lightest winds. The predominant wind direction is from the southwest.[98]

| Climate data for Bath (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.6 (70.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.5 (47.3) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.6 (51.1) |

12.6 (54.7) |

12.5 (54.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 83.2 (3.28) |

56.9 (2.24) |

58.0 (2.28) |

57.8 (2.28) |

58.7 (2.31) |

54.5 (2.15) |

57.7 (2.27) |

73.9 (2.91) |

63.0 (2.48) |

86.4 (3.40) |

88.7 (3.49) |

90.6 (3.57) |

829.9 (32.67) |

| Average rainy days(≥ 1 mm) | 13.2 | 10.8 | 10.1 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 9.4 | 9.6 | 10.6 | 9.5 | 12.1 | 13.6 | 13.5 | 132.9 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 56.1 | 68.2 | 128.7 | 161.2 | 197.3 | 192.1 | 210.9 | 198.0 | 146.6 | 104.0 | 67.0 | 51.1 | 1,581.9 |

| Source:Met Office[99] | |||||||||||||

Green belt

[edit]Bath is fully enclosed bygreen beltas a part of a wider environmental and planning policy first designated in the late 1950s,[100]and this extends into much of the surrounding district and beyond, helping to maintain local green space, prevent furtherurban sprawland unplanned expansion towards Bristol andBradford-on-Avon, as well as protecting smaller villages in between.[100]Suburbs of the city bordering the green belt includeBatheaston,Bathford,Bathampton, the University of Bath campus, Ensleigh,Twerton,Upper Weston,Odd Down, andCombe Down.

Parts of the CotswoldsAONBsouthern extent overlap the green belt north of the city, with other nearby landscape features and facilities within the green belt including the River Avon, Kennet and Avon Canal,Bath Racecourse, Bath Golf Club,Bathampton Down, Bathampton Meadow Nature Reserve, Bristol and Bath Railway Path, theCotswold Way,Limestone Linkroute, Pennyquick Park,Little Solsbury Hill, and Primrose Hill.[100]

Demography

[edit]District

[edit]

According to the2011 census, Bath, together with North East Somerset, which includes areas around Bath as far as theChew Valley, had a population of 176,015.Demographyshows according to the same statistics, the district is overwhelmingly populated by people of a white background at 94.6% – significantly higher than the national average of 87.17%. Other ethnic groups in the district, in order of population size, aremultiracialat 1.6%, Asian at 2.6% and black at 0.8% (the national averages are 1.98%, 6.92% and 3.01%, respectively).[101]

The district is largelyChristianat 56.5%, with no other religion reaching more than 0.7%. These figures generally compare with the national averages, though thenon-religious, at 32.7%, are significantly more prevalent than the national 25.67%. 83.9% of residents rated their health as good or very good, higher than the national level (81.40%). Nationally, 18% of people describe themselves as having a long-term illness; in Bath it is 16.10%.[101]

City

[edit]|

|

This section needs to be

updated.

(March 2024)

|

The2011 censusrecorded a population of 94,782 for the Bath built-up area and 88,859 for the city, with the latter exactly corresponding to the boundaries of the parliament constituency.[102]The Bath built-up area extends slightly beyond the boundaries of the city itself, taking in areas to the northeast such asBathamptonandBathford. The 2001 census figure for the city was 83,992.[103]By 2019, the population was estimated at 90,000.[104]

An inhabitant of Bath is known as a Bathonian.[105]

The table below compares the city of Bath with the unitary authority district as a whole (including the city) andSouth West England.

| Ethnic groups 2011 | Bath city | Bath and North East Somerset | South West England |

|---|---|---|---|

| White British | 85.0% | 90.1% | 91.8% |

| Asian | 4.2% | 2.6% | 2.0% |

| Black | 1.2% | 0.7% | 0.9% |

| Other White | 4.7% | 4.4% | 3.6%[106] |

Economy

[edit]Industry

[edit]Bath once had an important manufacturing sector, particularly in crane manufacture, furniture manufacture, printing, brass foundries, quarries, dye works andPlasticinemanufacture, as well as many mills.[109]Significant Bath companies includedStothert & Pitt,Bath Cabinet MakersandBath & Portland Stone.

During and afterWorld War IIBath was a major location ofMinistry of Defenceoffices, with three major sites on the outskirts of Bath (Ensleigh, Foxhill and Warminster Road) and a number of smaller central offices including theEmpire Hotel. After theCold Warstaff numbers declined, and from 2010 to 2013 about 2,600 remaining staff were moved toMoD Abbey Woodin Bristol. In 2013 the three major sites were sold for the development of over 1,000 new houses.[110][111]

Nowadays, manufacturing is in decline, but the city boasts strong software, publishing and service-oriented industries, and the international manufacturing companyRotorkhas its headquarters in the city.[112]The city's attraction to tourists has also led to a significant number of jobs in tourism-related industries. Important economic sectors in Bath include education and health (30,000 jobs), retail, tourism and leisure (14,000 jobs) and business and professional services (10,000 jobs).[113]

Major employers are theNational Health Service, the city's two universities, and Bath and North East Somerset Council. Growing employment sectors include information and communication technologies and creative and cultural industries where Bath is one of the recognised national centres for publishing,[113]with the magazine and digital publisherFuture plcemploying around 650 people. Others includeBuro Happold(400) andIPL Information Processing Limited(250).[114]The city boasts over 400 retail shops, half of which are run by independent specialist retailers, and around 100 restaurants and cafes primarily supported by tourism.[113]

Tourism

[edit]

One of Bath's principal industries is tourism, with annually more than one million staying visitors and 3.8 million day visitors.[113]The visits mainly fall into the categories ofheritage tourismandcultural tourism, aided by the city's selection in 1987 as a World Heritage Site in recognition of its international cultural importance.[65]All significant stages of thehistory of Englandare represented within the city, from the Roman Baths (including their significantCelticpresence), to Bath Abbey and the Royal Crescent, to the more recent Thermae Bath Spa.

The size of the tourist industry is reflected in the almost 300 places of accommodation – including more than 80 hotels, two of which have 'five-star' ratings,[115]over 180bed and breakfasts– many of which are located inGeorgian buildings, and two campsites located on the western edge of the city. The city also has about 100 restaurants and a similar number ofpubsand bars.

Several companies offeropen top bustours around the city, as well as tours on foot and on the river. Since the opening of Thermae Bath Spa in 2006, the city has attempted to recapture its historical position as the only town or city in the United Kingdom offering visitors the opportunity to bathe in naturally heated spring waters.[116]

In the 2010Google Street ViewBest Streets Awards, the Royal Crescent took second place in the "Britain's Most Picturesque Street" award, first place being given toThe ShamblesinYork.Milsom Streetwas also awarded "Britain's Best Fashion Street" in the 11,000-strong vote.[117][118]

Architecture

[edit]There are many Romanarchaeologicalsites throughout the central area of the city. Thebathsthemselves are about 6 metres (20 ft) below the present city street level. Around the hot springs, Roman foundations, pillar bases, and baths can still be seen; however, all thestoneworkabove the level of the baths is from more recent periods.[119]

Bath Abbey was aNormanchurch built on earlier foundations. The present building dates from the early 16th century and shows alate Perpendicularstyle withflying buttressesandcrocketedpinnaclesdecorating acrenellatedand piercedparapet.[120]The choir and transepts have afan vaultbyRobertandWilliam Vertue.[121]A matching vault was added to the nave in the 19th century.[122]The building is lit by 52 windows.[123]

Most buildings in Bath are made from the local, golden-coloured Bath stone,[124]and many date from the 18th and 19th century. The dominant style of architecture in Central Bath is Georgian;[125]this style evolved from thePalladianrevival style that became popular in the early 18th century. Many of the prominent architects of the day were employed in the development of the city. The original purpose of much of Bath's architecture is concealed by the honey-coloured classical façades; in an era before the advent of the luxury hotel, these apparently elegant residences were frequently purpose-built lodging houses, where visitors could hire a room, a floor, or (according to their means) an entire house for the duration of their visit, and be waited on by the house's communalservants.[126]The masonsReeves of Bathwere prominent in the city from the 1770s to 1860s.[127]

The Circus consists of three long, curved terraces designed by the elder John Wood to form a circular space or theatre intended for civic functions and games. The games give a clue to the design, the inspiration behind which was theColosseumin Rome.[128]Like the Colosseum, the three façades have a different order of architecture on each floor:Doricon the ground level, thenIonicon thepiano nobile, and finishing withCorinthianon the upper floor, the style of the building thus becoming progressively more ornate as it rises.[128]Wood never lived to see his unique example of town planning completed as he died five days after personally laying the foundation stone on 18 May 1754.[128]

The most spectacular of Bath's terraces is the Royal Crescent, built between 1767 and 1774 and designed by the younger John Wood.[129]Wood designed the great curved façade of what appears to be about 30 houses with Ioniccolumnson a rusticated ground floor, but that was the extent of his input: each purchaser bought a certain length of the façade, and then employed their own architect to build a house to their own specifications behind it; hence what appears to be two houses is in some cases just one. This system of town planning is betrayed at the rear of the crescent: while the front is completely uniform and symmetrical, the rear is a mixture of differing roof heights, juxtapositions and fenestration. The "Queen Anne fronts and Mary-Anne backs" architecture occurs repeatedly in Bath and was designed to keep hired women at the back of the house.[130][131][132]Other fine terraces elsewhere in the city include Lansdown Crescent[133]andSomerset Placeon the northern hill.[134]

Around 1770 theneoclassicalarchitectRobert AdamdesignedPulteney Bridge, using as the prototype for the three-arched bridge spanning the Avon an original, but unused, design byAndrea Palladiofor theRialto Bridgein Venice.[135]Thus, Pulteney Bridge became not just a means of crossing the river, but also a shopping arcade. Along with the Rialto Bridge and thePonte VecchioinFlorence, which it resembles, it is one of the very few surviving bridges in Europe to serve this dual purpose.[135]It has been substantially altered since it was built. The bridge was named after Frances andWilliam Pulteney, the owners of the Bathwick estate for which the bridge provided a link to the rest of Bath.[135]The Georgian streets in the vicinity of the river tended to be built high above the original ground level to avoid flooding, with the carriageways supported on vaults extending in front of the houses. This can be seen in the multi-storey cellars around Laura Place south of Pulteney Bridge, in the colonnades below Grand Parade, and in the grated coal holes in the pavement of North Parade. In some parts of the city, such as George Street, and London Road near Cleveland Bridge, the developers of the opposite side of the road did not match this pattern, leaving raised pavements with the ends of the vaults exposed to a lower street below.

The heart of the Georgian city was the Pump Room, which, together with its associated Lower Assembly Rooms, was designed byThomas Baldwin, a local builder responsible for many other buildings in the city, including the terraces in Argyle Street[136]and theGuildhall.[137]Baldwin rose rapidly, becoming a leader in Bath's architectural history.

In 1776, he was made the chiefCity Surveyor, andBath City Architect.[138]Great Pulteney Street, where he eventually lived, is another of his works: this wideboulevard, constructed around 1789 and over 1,000 feet (305 m) long and 100 feet (30 m) wide, is lined on both sides by Georgian terraces.[139][140]

In the 1960s and early 1970s some parts of Bath were unsympathetically redeveloped, resulting in the loss of some 18th- and 19th-century buildings. This process was largely halted by a popular campaign which drew strength from the publication of Adam Fergusson'sThe Sack of Bath.[141]Controversy has revived periodically, most recently with the demolition of the 1930s Churchill House, a neo-Georgian municipal building originally housing the Electricity Board, to make way for a newbus station. This is part of the Southgate redevelopment in which an ill-favoured 1960s shopping precinct, bus station and multi-storey car park were demolished and replaced by a new area ofneo-Georgianshopping streets.[142][143]

As a result of this and other changes, notably plans for abandoned industrial land along the Avon, the city's status as a World Heritage Site was reviewed by UNESCO in 2009.[144]The decision was made to let Bath keep its status, but UNESCO asked to be consulted on future phases of the Riverside development,[145]saying that the density and volume of buildings in the second and third phases of the development need to be reconsidered.[146]It also demanded Bath do more to attract world-class architecture in new developments.[146]

In 2021, Bath received its second UNESCO World Heritage inscription, becoming part of a group of 11 spa towns across seven countries that were listed by UNESCO as the "Great Spas of Europe".[73]

Culture

[edit]

Bath became the centre of fashionable life in England during the 18th century when its Old Orchard Street Theatre andarchitecturaldevelopments such as Lansdown Crescent,[147]the Royal Crescent,[148]The Circus, and Pulteney Bridge were built.[149]

Bath's five theatres –Theatre Royal,Ustinov Studio,the Egg, theRondo Theatre, and theMission Theatre– attract internationally renowned companies and directors and an annual season bySir Peter Hall. The city has a long-standing musical tradition; Bath Abbey, home to theKlais Organand the largest concert venue in the city,[150]stages about 20 concerts and 26 organ recitals each year. Another concert venue, the 1,600-seatart decoThe Forum, originated as a cinema. The city holds the annualBath International Music Festivaland Mozartfest, the annualBath Literature Festival(and itscounterpart for children), theBath Film Festival, the Bath Digital Festival. theBath Fringe Festival, theBath Beer Festivaland theBath Chilli Festival. The Bach Festivals occur at two and a half-year intervals. An annualBard of Bathcompetition aims to find the best poet, singer or storyteller.[151]

The city is home to theVictoria Art Gallery,[152]theMuseum of East Asian Art, andHolburne Museum,[153]numerous commercial art galleries and antique shops, as well as a number of other museums, among themBath Postal Museum, theFashion Museum, theJane Austen Centre, theHerschel Museum of Astronomyand the Roman Baths.[154]TheBath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution(BRLSI) in Queen Square was founded in 1824 from the Society for the encouragement of Agriculture, Planting, Manufactures, Commerce and the Fine Arts founded in 1777.[155]In September 1864, BRLSI hosted the 34th annual meeting of theBritish Science Association, which was attended by explorersDavid Livingstone,Sir Richard Francis Burton, andJohn Hanning Speke. The history of the city is displayed at theMuseum of Bath Architecture, which is housed in a building built in 1765 as the TrinityPresbyterianChurch. It was also known as theCountess of Huntingdon'sChapel, as she lived in the attached house from 1707 to 1791.[156]

The arts

[edit]

During the 18th centuryThomas GainsboroughandSir Thomas Lawrencelived and worked in Bath.[157][158]John Maggs, a painter best known for coaching scenes, was born and lived in Bath with his artistic family.[159]

Jane Austenlived there from 1801 with her father, mother and sister Cassandra, and the family resided at four different addresses until 1806.[160]Jane Austen never liked the city, and wrote to Cassandra, "It will be two years tomorrow since we left Bath for Clifton, with what happy feelings of escape."[161]Bath has honoured her name with the Jane Austen Centre and a city walk. Austen'sNorthanger AbbeyandPersuasionare set in the city and describe taking the waters, social life, and music recitals.

William Friese-Greeneexperimented with celluloid and motion pictures in his studio in the 1870s, developing some of the earliest movie camera technology. He is credited as being one of the inventors ofcinematography.[162]

Satirist and political journalistWilliam Honewas born in Bath in 1780.

Taking the waters is described inCharles Dickens' novelThe Pickwick Papersin which Pickwick's servant,Sam Weller, comments that the water has "a very strong flavour o' warm flat irons". The Royal Crescent is the venue for a chase between two characters, Dowler and Winkle.[163]Moyra Caldecott's novelThe Waters of Sulis set in Roman Bath in AD 72, andThe Regency Detective, byDavid LassmanandTerence James, revolves around the exploits of Jack Swann investigating deaths in the city during the early 19th century.[164]Richard Brinsley Sheridan's playThe Rivalstakes place in the city,[165]as doesRoald Dahl's chillingshort story,The Landlady.[166]

Many films and television programmes have been filmed using its architecture as the backdrop, including the 2004filmofThackeray'sVanity Fair,[167]The Duchess(2008),[167]The Elusive Pimpernel(1950)[167]andThe Titfield Thunderbolt(1953).[167]In 2012, Pulteney Weir was used as a replacement location during post production of the film adaptation ofLes Misérables. Stunt shots were filmed in October 2012 after footage acquired during the main filming period was found to have errors.[168]The ITV police dramaMcDonald and Doddsis set and mostly filmed in Bath using many of the city's famous sites.[169]

In August 2003The Three Tenorssang at a concert to mark the opening of the Thermae Bath Spa, a new hot waterspain the city centre, but delays to the project meant the spa actually opened three years later on 7 August 2006.[170]In 2008, 104 decorated pigs were displayed around the city in a public art event called "King Bladud's Pigs in Bath". It celebrated the city, its origins and artists. Decorated pig sculptures were displayed throughout the summer and were auctioned to raise funds forTwo Tunnels Greenway.[171]

Parks

[edit]

Royal Victoria Park, a short walk from the city centre, was opened in 1830 by the 11-year-oldPrincess Victoria, and was the first park to carry her name.[172]Thepublic parkis overlooked by the Royal Crescent and covers 23 hectares (57 acres).[173]It has[173]askatepark, tennis courts, abowling green, a putting green and a 12- and 18-hole golf course, a pond, open-air concerts, an annualtravelling funfairat Easter,[174]and a children's play area. Much of its area islawn; a notable feature is aha-hathat segregates it from the Royal Crescent while giving the impression from the Crescent of uninterrupted grassland across the park to Royal Avenue. It has a "Green Flag Award", the national standard for parks and green spaces in England and Wales, and is registered byEnglish Heritageas ofNational Historic Importance.[175]The 3.84-hectare (9.5-acre) botanical gardens were formed in 1887 and contain one of the finest collections of plants on limestone in theWest Country.[176]

A replica Roman Temple was built at theBritish Empire ExhibitionatWembleyin 1924, and, following the exhibition, was dismantled and rebuilt in Victoria Park in Bath.[177]In 1987, the gardens were extended to include the Great Dell, a disused quarry with a collection ofconifers.[178]

Other parks include Alexandra Park on a hill overlooking the city;Parade Gardens, along the river near the abbey in the city centre;Sydney Gardens, an 18th-century pleasure garden; Henrietta Park; Hedgemead Park; and Alice Park.Jane Austenwrote "It would be pleasant to be near the Sydney Gardens. We could go into the Labyrinth every day."[179]Alexandra, Alice and Henrietta parks were built into the growing city among the housing developments.[180]Linear Park is built on the oldSomerset and Dorset Joint Railwayline,[181]and connects with theTwo Tunnels Greenwaywhich contains the longest cycling and walking tunnel in the UK.Cleveland Poolswere built around 1815 close to the River Avon,[182]now the oldest surviving public outdoorlidoin England.[183]Restoration was completed in 2023, after a 20 year fund-raising campaign, with the lido opening for the first time in 40 years on 10 September.[184]

Queen Victoria

[edit]Victoria Art Gallery and Royal Victoria Park are named afterQueen Victoria, who wrote in her journal in 1837, "The people are really too kind to me."[185]This feeling seemed to have been reciprocated by the people of Bath: "Lord James O'Brien brought a drawing of the intended pillar which the people of Bath are so kind as to erect in commemoration of my 18th birthday."[185]

Food

[edit]

Several foods have an association with the city.Sally Lunn buns(a type ofteacake) have long been baked in Bath. They were first mentioned by name in verses printed in theBath Chronicle, in 1772.[186]At that time they were eaten hot at public breakfasts in Spring Gardens. They can be eaten with sweet or savoury toppings and are sometimes confused withBath buns, which are smaller, round, very sweet and very rich. They were associated with the city followingThe Great Exhibition. Bath buns were originally topped with crushedcomfitscreated by dippingcarawayseeds repeatedly in boiling sugar; but today seeds are added to a 'London Bath Bun' (a reference to the bun's promotion and sale at the Great Exhibition).[187]The seeds may be replaced by crushed sugar granules or 'nibs'.[188]

Bath has lent its name to one other distinctive recipe –Bath Olivers– a dry baked biscuit invented by Dr William Oliver, physician to theMineral Water Hospitalin 1740.[189]Oliver was an anti-obesity campaigner and author of a"Practical Essay on the Use and Abuse of warm Bathing in Gluty Cases".[189]In more recent years, Oliver's efforts have been traduced by the introduction of a version of the biscuit with a plain chocolate coating.Bath chaps, the salted and smoked cheek and jawbones of the pig, takes its name from the city[190]and is available from a stall in the daily covered market.Bath Alesbrewery is located inWarmleyandAbbey Alesare brewed in the city.[191]

Twinning

[edit]Bath istwinnedwith four other cities in Europe. Twinning is the responsibility of the Charter Trustees and each twinning arrangement is managed by a Twinning Association.[192][193]

There is also a historic connection withManly, New South Wales, Australia, which is referred to as a sister city; a partnership arrangement withBeppu,Ōita Prefecture, Japan;[193]and a friendship agreement withOleksandriia,Kirovohrad Oblast, Ukraine.[194]

Formal twinning

[edit]- Aix-en-Provence, France[193][195]

- Alkmaar, Netherlands[193]

- Braunschweig, Germany[193][196]

- Kaposvár, Hungary[193]

Education

[edit]

Bath has two universities, theUniversity of BathandBath Spa University. Established in 1966, the University of Bath[197]was named University of the Year byThe Sunday Timesin 2011. It offers programs in politics, languages, the physical sciences, engineering, mathematics, architecture, management and technology.[198]

Bath Spa University was first granted degree-awarding powers in 1992 as auniversity collegebefore being granted university status in August 2005.[199][200]It offers courses leading to aPostgraduate Certificate in Education. It has schools in the following subject areas: Art and Design, Education, English and Creative Studies, Historical and Cultural Studies, Music and the Performing Arts, Science and the Environment and Social Sciences.[201]

Bath Collegeoffersfurther education, andNorland Collegeprovides education and training in childcare.[202]

Sport

[edit]Rugby

[edit]

Bath Rugbyis arugby unionteam in thePremiershipleague. It plays in blue, white and black kit at theRecreation Groundin the city, where it has been since the late 19th century, following its establishment in 1865.[203]The team's first major honour was winning the John Player Cup, now sponsored as theLVCup and also known as theAnglo-Welsh Cup, four years consecutively from 1984 until 1987.[203]The team then led theCourage leaguein six seasons in eight years between 1988 and 1989 and 1995–96, during which time it also won the renamed Pilkington Cup in 1989, 1990, 1992, 1994, 1995 and 1996.[203]It finally won theHeineken Cupin the 1997–98 season, and topped the Zürich Premiership (now Gallagher Premiership) in 2003–04.[203]The team'ssquadincludes several members who also play, or have played in theEnglish national team, includingLee Mears,Rob Webber,Dave Attwood,Nick AbendanonandMatt Banahan.Colston's School, Bristol, has had a large input in the team over the past decade,[vague]providing several current 1st XV squad members.[citation needed]The former England Rugby Team Manager and formerScotland nationalcoachAndy Robinsonused to play for Bath Rugby team and was captain and later coach. Both of Robinson's predecessors,Clive WoodwardandJack Rowell, as well as his successorBrian Ashton, were also former Bath coaches and managers.[204]

Football

[edit]

Bath City F.C.is the semi-professionalfootballteam. Founded in 1889, the club has played their home matches atTwerton Parksince 1932. Bath City's history is entirely in non-league football, predominantly in the 5th tier. Bath narrowly missed out on election to the Football League by a few votes in 1978[205]and again in 1985. The club have a good history in the FA Cup, reaching the third round six times. The record attendance, 18,020, at the ground was in 1960 against Brighton.[206][207]The club's colours are black and white and their official nickname is "The Romans", stemming from Bath's Ancient Roman history.[208]The club is sometimes called "The Stripes", referring to their striped kit.

Until 2009Team Bath F.C.operated as an affiliate to the University Athletics programme. In 2002, Team Bath became the first university team to enter theFA Cupin 120 years, and advanced through four qualifying rounds to the first round proper.[209]The university's team was established in 1999 while the city team has existed since before 1908 (when it entered theWestern League).[210]However, in 2009, theFootball Conferenceruled that Team Bath would not be eligible to gain promotion to a National division, nor were they allowed to participate inFootball Associationcup competitions. This ruling led to the decision by the club to fold at the end of the 2008–09 Conference South competition. In their final season, Team Bath F.C. finished 11th in the league.[211]

Bath also hasNon-League footballclubsOdd Down F.C.who play at the Lew Hill Memorial Ground[212]andLarkhall Athletic F.C.who play at Plain Ham.

Other sports

[edit]Manycricketclubs are based in the city, includingBath Cricket Club, who are based at the North Parade Ground and play in theWest of England Premier League. Cricket is also played on the Recreation Ground, just across from the rugby club. The Recreation Ground is also home to Bath Croquet Club, which was re-formed in 1976 and is affiliated with the South West Federation ofCroquetClubs.[213]

TheBath Half Marathonis run annually through the city streets, with over 10,000 runners.[214]

TeamBathis the umbrella name for all of the University of Bath sports teams, including the aforementioned football club. Other sports for which TeamBath is noted areathletics, badminton, basketball,bob skeleton,bobsleigh,hockey, judo,modern pentathlon,netball, rugby union, swimming, tennis,triathlonand volleyball. The City of Bath Triathlon takes place annually at the university.[215]

Bath Roller Derby Girls (BRDG)is a flat trackroller derbyclub, founded in 2012,[216]they compete in the British Roller Derby Championships Tier 3.[217]As of 2015, they are full members of the United Kingdom Roller Derby Association (UKRDA.)[218]

Bath is home to atable tennisLeague, made up of 3 divisions and a number of clubs based in Bath and the surrounding area.[219]

Transport

[edit]Roads

[edit]

Bath is approximately 11 miles (18 km) south-east of the larger city and port of Bristol, to which it is linked by theA4 road, which runs through Bath, and is a similar distance south of theM4 motorwayat junction 18. The potential new junction 18a linking theM4 motorwaywith the A4174Avon Ring Roadwill provide an additional direct route from Bath to the motorway.[220]

In an attempt to reduce the level of car use,park and rideschemes have been introduced, with sites at Odd Down, Lansdown and Newbridge. A very large increase in city centre parking was also provided under the new SouthGate shopping centre development, which necessarily introduces more car traffic. In addition, abus gatescheme in Northgate aims to reduce private car use in the city centre.[221]

Atransportation study(theBristol/Bath to South Coast Study) was published in 2004 after being initiated by theGovernment Office for the South WestandBath and North East Somerset Council[222]and undertaken byWSP Global[222]as a result of thede-trunkingin 1999 of the A36/A46 trunk road network[223]from Bath to Southampton.

TheBath Clean Air Zonewas introduced for central Bath on 15 March 2021. A Class C zone, it charges themost polluting commercial vehicles£9 per day (and up to £100 per day for coaches andHGVs).[224]It is the first UK road pollution charging zone outside London, and reducednitrogen dioxidelevels in the city by 26% over the following two years, meeting legal standards.[225]

Buses

[edit]National Expressoperatescoachservices fromBath bus stationto a number of cities. Bath has a network of bus routes run byFirst West of England, with services to surrounding towns and cities, such asBristol,Corsham,Chippenham,Devizes,Salisbury,FromeandWells.Faresaver Busesalso operate services to surrounding towns. TheBath Bus Companyruns open-top double-decker bus tours around the city, as well as frequent services toBristol Airport.Stagecoach Westalso provides services toTetburyand the South Cotswolds.[226]The suburbs of Bath are also served by theWESTlink on demand service, available Monday to Saturday.[227]

Cycling

[edit]Bath is onNational Cycle Route 4, with one of Britain's firstcycleways, theBristol and Bath Railway Path, to the west, and an eastern route toward London on the canal towpath. Bath is about 20 miles (30 km) fromBristol Airport.[228]Bath also benefits from several bridleways and byways.[229]

Rivers and canals

[edit]The city is connected to Bristol and the sea by the River Avon, navigable vialocksby small boats. The river was connected to theRiver Thamesand London by theKennet and Avon Canalin 1810 viaBath Locks; this waterway – closed for many years but restored in the last years of the 20th century – is now popular withnarrowboatusers.[230]

Railways

[edit]

Bath is served by theBath Spa railway station(designed byIsambard Kingdom Brunel), which has regular connections to LondonPaddington,Bristol Temple Meads,Cardiff Central,Cheltenham,Exeter,PlymouthandPenzance(seeGreat Western Main Line), and alsoWestbury,Warminster,Weymouth,Salisbury,Southampton,PortsmouthandBrighton(seeWessex Main Line). Services are provided byGreat Western Railway. There is a suburban station on the main line,Oldfield Park, which has a limited commuter service to Bristol as well as other destinations.

Green Park Stationwas once the terminus of theMidland Railway,[231]and junction for theSomerset and Dorset Joint Railway, whose line, always steam hauled, went through the Devonshire tunnel (under the Wellsway, St Luke's Church and the Devonshire Arms), through theCombe Down Tunneland climbed over theMendipsto serve many towns and villages on its 71-mile (114 km) run toBournemouth. This example of an English rural line was closed byBeechingin March 1966. Its Bath station building, now restored, houses shops, small businesses, the Saturday Bath Farmers Market and parking for a supermarket, while the route of the Somerset and Dorset within Bath has been reused for the Two Tunnels Greenway, a shared use path that extendsNational Cycle Route 24into the city.[232]

Trams

[edit]Historical

[edit]TheBath Tramways Companywas introduced in the late 19th century, opening on 24 December 1880. The4 ft(1,219 mm) gauge cars were horse-drawn along a route from London Road to the Bath Spa railway station, but the system closed in 1902. It was replaced by electric tram cars on a greatly expanded4 ft8+1⁄2in(1,435 mm) gauge system that opened in 1904. This eventually extended to 18 miles (29 km) with routes to Combe Down, Oldfield Park, Twerton,Newton St Loe, Weston andBathford. There was a fleet of 40 cars, all but 6 being double deck. The first line to close was replaced by a bus service in 1938, and the last went on 6 May 1939.[233]

Possible re-introduction

[edit]In 2005, a detailed plan was created and presented to the council to re-introduce trams to Bath, but the plan did not proceed, reportedly due to the focus by the council on the government-supported busway planned to run from the Newbridge park and ride into the city centre. Part of the justification for the proposed tram reintroduction plan was the pollution from vehicles within the city, which was twice the legal levels, and the heavy traffic congestion due to high car usage. In 2015[234]another group, Bath Trams, building on the earlier tram group proposals, created interest in the idea of re-introducing trams with several public meetings and meetings with the council.[235]In 2017,Bath and North East Somerset Councilannounced a feasibility study, due to be published by March 2018[needs update], into implementing a light rail or tram system in the city.[236]

In November 2016, theWest of England Local Enterprise Partnershipbegan a consultation process on their Transport Vision Summary Document, outlining potentiallight rail/tramroutes in the region, one of which being a route fromBristol city centrealong theA4 roadto Bath to relieve pressure on bus and rail services between the two cities.[237]

Media

[edit]Bath's local newspaper is theBath Chronicle, owned byLocal World. Published since 1760, theChroniclewas a daily newspaper until mid-September 2007, when it became a weekly.[238]Since 2018 its website has been operated byTrinity Mirror'sSomerset Liveplatform.[239]

TheBBC Bristolwebsite has featured coverage of news and events within Bath since 2003.[240]

For television, Bath is served by theBBC Weststudiosbased in Bristol, and byITV West Country, formerly HTV, also from studios in Bristol.[241]

Radio stations broadcasting to the city includeBBC Radio Bristolwhich has a studio in Kingsmead Square in the city centre,BBC Radio SomersetinTaunton,Greatest Hits Radio Bristol & The South Weston 107.9FM andHeart West, formerly GWR FM, as well as The University of Bath'sUniversity Radio Bath, a student-focused radio station available on campus and also online.[242]Launched in 2019,BA1 Radiois an onlinecommunity radio station.[243]

See also

[edit]- TheBathonianAge (168.3 – 166.1 million years ago), aJurassicPeriod of geological time named after Bath

- Grade I listed buildings in Bath and North East Somerset

- List of people from Bath

- List of spa towns in the United Kingdom

- Bath, Ontario, named after Bath, Somerset, and now part ofLoyalist, Ontario

References

[edit]- ^ab"Bath".City population. Retrieved25 October2022.

- ^Wells, John C.(2008).Longman Pronunciation Dictionary(3rd ed.). Longman.ISBN978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^Altendorf, Ulrike; Watt, Dominic (2004). "The dialects in the South of England: phonology". In Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.).A Handbook of Varieties of English. Vol. 1: Phonology. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 178–203.ISBN978-3-11-017532-5.Page 199.

- ^"100 Largest Cities and Towns in the UK by Population".The Geographist. 4 May 2019. Retrieved5 January2022.

- ^"Visitors and tourists: Bath and North East Somerset Council".beta.bathnes.gov.uk. 19 January 2022. Retrieved6 January2023.

- ^"Travel trends – Office for National Statistics".www.ons.gov.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved17 December2020.

- ^"Experience Bath – Tailor-made visits to Bath".Archivedfrom the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved16 December2020.

- ^Wessex Archaeology."Archaeological Desk- based Assessment"(PDF).University of Bath, Masterplan Development Proposal 2008. Bath University.Archived(PDF)from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved4 May2015.

- ^"Monument No. 204162".PastScape. Historic England. Archived fromthe originalon 4 May 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Thomas, Rod (2008).A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. p. 21.ISBN978-0-948975-86-8.

- ^"The Beaker people and the Bronze Age".Somerset County Council.Archivedfrom the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Charmy Down".Pastscape. Historic England.Archivedfrom the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved22 August2017.

- ^Thomas, Rod (2008).A Sacred landscape: The prehistory of Bathampton Down. Bath: Millstream Books. pp. 46–48.ISBN978-0-948975-86-8.

- ^"Bathampton Camp".PastScape. Historic England. Archived fromthe originalon 4 May 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"History of Bath's Spa". Bath Tourism Plus.Archivedfrom the original on 15 March 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Page, William."Romano-British Somerset: Part 2, Bath".British History Online. Victoria County History.Archivedfrom the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^A L Rowse,Heritage of Britain, 1995, Treasure of London,ISBN978-0-907407-58-4, 184 pages, Page 15

- ^"A Corpus of Writing-Tablets from Roman Britain".Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, Oxford.Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"City of Bath World Heritage Site Management Plan".Bath and North East Somerset. Archived fromthe originalon 14 June 2007. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"The Roman Baths".TimeTravel Britain.Archivedfrom the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^ab"Alfreds Borough".Bath Past.Archivedfrom the original on 11 June 2009. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Southern, Patricia (2012).The Story of Roman Bath. Amberley. pp. 202–203.ISBN978-1445610900.

- ^Hough, Andrew (22 March 2012)."Hoard of 30,000 silver Roman coins discovered in Bath".The Daily Telegraph.Archivedfrom the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved4 May2015.

- ^"Dobunni to Hwicce".Bath past.Archivedfrom the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"History of Bath England, Roman Bath history".My England Travel Guide.Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Klinck, Anne (1992).The Old English Elegies: A Critical Edition and Genre Study. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 61.

- ^Davenport, Peter (2002).Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 31–34.ISBN978-0752419657.

- ^"Timeline Bath".Time Travel Britain.Archivedfrom the original on 3 April 2008. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Saint David".100 Welsh Heroes. Archived fromthe originalon 10 October 2012. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Campbell, James; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991).The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin. pp. 40–41.ISBN978-0140143959.

- ^"Bath Abbey".Robert Poliquin's Music and Musicians. Quebec University. Archived fromthe originalon 21 June 2013. Retrieved18 September2007.

- ^Churton, Edward(1841).The Early English Church(2nd ed.). London: James Burns. p. 102.

- ^Davenport, Peter (2002).Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 40–42.ISBN978-0752419657.

- ^Davenport, Peter (2002).Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 50–51.ISBN978-0752419657.

- ^"Edgar the Peaceful".English Monarchs – Kings and Queens of England.Archivedfrom the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Powicke, Maurice(1939).Handbook of British Chronology. Offices of the Royal Historical Society. p. 137.ISBN978-0-901050-17-5.

- ^Barlow, Frank(March 2000).William Rufus. Yale University Press. p. 182.ISBN978-0-300-08291-3.

- ^Davenport, Peter (2002).Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. p. 71.ISBN978-0752419657.

- ^Huscroft, Richard (2004).Ruling England, 1042–1217. Routledge. p. 128.ISBN978-0582848825.

- ^Taylor, Ann (1999).Bath Abbey 1499-1999. Bath Abbey. p. 3.

- ^"The eight-hundred-year story of St John's Hospital, Bath".Spirit of Care. Jean Manco.Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Manco, Jean."Shelter in old age". Bath Past.Archivedfrom the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Davenport, Peter (2002).Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 97–98.ISBN978-0752419657.

- ^"Bath Abbey".Visit Bath.Archivedfrom the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Renaissance Bath".City of Bath.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved9 December2007.

- ^"Civic Insignia".City of Bath.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved10 December2007.

- ^Stout, Adam (2020).Glastonbury Holy Thorn: Story of a Legend. Green & Pleasant Publishing. pp. 28–29.ISBN9781916268616.

- ^Green, Emanuel (1893). "The Visits to Bath of Two Queens".Proceedings of the Bath Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club.7: 224.

- ^Crutwell, Clement (1801).A tour through the whole island of Great Britain; Divided into Journeys. Interspersed with Useful Observations; Particularly Calculated for the Use of Those who are Desirous of Travelling over England & Scotland. Vol. 2. pp. 387–388. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Rodgers, Colonel Hugh Cuthbert Basset (1968).Battles and Generals of the Civil Wars. Seeley Service & Co. p. 81.ASINB000HJ9TUG.

- ^abcWroughton, John (2004).Stuart Bath: Life in the Forgotten City 1603–1714. The Lansdown Press. pp. 156, 158, 161–2, 174.

- ^Burns, D. Thorburn (1981). "Thomas Guidott (1638–1705): Physician and Chymist, contributor to the analysis of mineral waters".Analytical Proceedings.18(1): 2–6.doi:10.1039/AP9811800002.

- ^Hembury, Phylis May (1990).The English Spa, 1560–1815: A Social History. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press. pp. 114–121.ISBN978-0-8386-3391-5.

- ^"John Wood and the Creation of Georgian Bath".Building of Bath Museum. Archived fromthe originalon 13 November 2007. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^abcd"Ralph Allen Biography".Bath Postal Museum. Archived fromthe originalon 4 October 2013. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Eglin, John (2005).The Imaginary Autocrat: Beau Nash and the invention of Bath. Profile. p. 7.ISBN978-1-86197-302-3.

- ^"The manuscripts, Letter from Andrew Millar to Thomas Cadell, 16 July, 1765. Andrew Millar Project. University of Edinburgh".millar-project.ed.ac.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved3 June2016.

- ^Thorn, sir William (1816).A memoir of major-general sir R.R. Gillespie [by W. Thorn.].

- ^"A vision of Bath".Britain through time. University of Portsmouth.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved4 May2015.

- ^"Beckford's Tower & Mortuary Chapel, Lansdown Cemetery".Images of England. Historic England. Archived fromthe originalon 28 April 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"The Emperor Haile Selassie I in Bath 1936–1940".Anglo-Ethiopian Society.Archivedfrom the original on 30 January 2008. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"History – Bath at War".Royal Crescent Society, Bath. Archived fromthe originalon 31 January 2008. Retrieved9 December2007.

- ^abcSpence, Cathryn (2012).Bath in the Blitz: Then and Now. Stroud: The History Press. p. 55.ISBN978-0-7524-6639-2.

- ^ab"Royal Crescent History: The Day Bombs fell on Bath".Royal Crescent Society, Bath. Archived fromthe originalon 31 January 2008. Retrieved9 December2007.

- ^abc"Cultural and historical development of Bath".Bath City-Wide Character Appraisal. Bath & North East Somerset Council. 31 August 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Council Housing in Bath 1945-2013 – a social history"(PDF).Museum of Bath at Work. 2013. Retrieved27 August2023.

- ^"Brutal Bath"(PDF). Museum of Bath Architecture. 2014. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 30 November 2018. Retrieved30 November2018.

- ^"Why is Bath a World Heritage Site?". Bath and North East Somerset. 7 November 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 9 June 2015. Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^abcd"The Batman Rapist: What we know about the shocking serial attacker who terrorised women in Bath".Somerset Live. 1 August 2020. Retrieved15 June2022.

- ^"Parents plead for answers in 13-year-old murder case".The Independent. 9 October 2009. Retrieved15 June2022.

- ^"South Gate Bath".Morley.Archivedfrom the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved8 December2007.

- ^James Crawley (11 June 2016)."£12million for Bath Quays regeneration project is approved".Bath Chronicle. Archived fromthe originalon 30 September 2016. Retrieved22 July2016.

- ^abLandwehr, Andreas (24 July 2021)."'Great Spas of Europe' awarded UNESCO World Heritage status".Deutsche Presse-Agentur. Retrieved25 July2021.

- ^"Bath World Heritage Site | The City of Bath is exceptional in having two UNESCO inscriptions".www.bathworldheritage.org.uk. Retrieved18 May2024.

- ^Mayor of BathArchived1 November 2015 at theWayback MachineSaxon Bath

- ^Keane, Patrick (1973). "An English County and Education: Somerset, 1889–1902".The English Historical Review.88(347): 286–311.doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXVIII.CCCXLVII.286.

- ^"The Avon (Structural Change) Order 1995".HMSO.Archivedfrom the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^Bath and North East Somerset CouncilArchived17 October 2016 at theWayback MachineTwinning

- ^"The Charter Trustees of the City of Bath".Archivedfrom the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved2 June2019.

- ^"The Charter Trustees Regulations 1996". National Archives.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved4 May2015.

- ^"Bathnewseum". 12 March 2020.Archivedfrom the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved7 June2020.

- ^"Arms of The City of Bath".The City of Bath.Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved15 November2006.

- ^"File:Bath Guildhall, Council chamber, toward chair.jpg – Wikimedia Commons". Commons.wikimedia.org. 12 April 2011.Archivedfrom the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved30 October2019.

- ^"Bath (England)". Heraldry of the World. 9 September 2022. Archived fromthe originalon 18 April 2023. Retrieved18 April2023.

- ^Bath and North East Somerset CouncilArchived4 April 2019 at theWayback MachineBath City Forum

- ^"Bath Newseum". Archived fromthe originalon 28 August 2021. Retrieved28 August2021.

- ^"Parliamentary Constituencies in the unreformed House".United Kingdom Election Results. Archived fromthe originalon 5 November 2007. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Bath MP Don Foster says he will not stand at 2015 electionk".Bath Chronicle. 9 January 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 18 May 2015. Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^"Election maps – Great Britain". Ordnance Survey.Archivedfrom the original on 20 February 2016. Retrieved2 June2019.

- ^"Published Contaminated Land Inspection of the area surrounding Bath". Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived fromthe originalon 13 May 2012. Retrieved25 January2011.

- ^"Bath Western Riverside Outline Planning Application Design Statement, April 2006, Section 2.0, Site Analysis"(PDF). April 2006. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 10 August 2016. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^Ordnance Surveymapping

- ^"Carr's Mill, Lower Bristol Road, Bath Flood Risk Assessment"(PDF). Bath and North East Somerset. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 22 July 2011. Retrieved17 September2010.

- ^"Kensington Meadows". Natural England. Archived fromthe originalon 4 March 2016. Retrieved23 August2015.

- ^"Sacred Spring". Roman Baths Museum Web Site. Archived fromthe originalon 2 November 2007. Retrieved31 October2007.

- ^"Hot Water". Roman Baths Museum Web Site.Archivedfrom the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved31 October2007.

- ^"The Hot Springs of Bath: Geology, geochemistry, geophysics"(PDF). Bath and North East Somerset.Archivedfrom the original on 13 January 2014. Retrieved26 August2012.

- ^abcd"South West England: climate".Met Office.Archivedfrom the original on 25 February 2006. Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^"Bath (Bath and North East Somerset) UK climate averages - Met Office". Met Office. Retrieved4 July2024.

- ^abc"Bath & North East Somerset Green Belt Review – Stage 1 Report April 2013 – Green Belt history and policy origins"(PDF).bathnes.gov.uk.Archived(PDF)from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved14 February2018.

- ^ab"Bath and North East Somerset UA 2011 Census"(PDF).National Statistics.Archived(PDF)from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved1 May2017.

- ^ab"official labour market statistics". Nomisweb.co.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 30 September 2018. Retrieved30 October2019.

- ^Bath and North East Somerset CouncilArchived21 September 2015 at theWayback MachineBath and North East Somerset Cultural Strategy 2011– 2026 – page 40

- ^"Bath bans coaches, over complaints day-trippers only bring pollution".The Telegraph. 24 December 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved12 June2020.

- ^"'Bathonian' entry".Collins English Dictionary. Collins.Archivedfrom the original on 4 April 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Regional ethnic diversity".gov.uk.Archivedfrom the original on 9 September 2018.

- ^Services, Good Stuff IT."South West – UK Census Data 2011".UK Census Data.Archivedfrom the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved28 May2018.

- ^Services, Good Stuff IT."Bath and North East Somerset – UK Census Data 2011".UK Census Data.Archivedfrom the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved28 May2018.

- ^"Mill's integral role in city's rich industrial heritage".Bath Chronicle. 28 April 2011. Archived fromthe originalon 9 October 2015. Retrieved2 October2015.

- ^"Abbey Wood expansion to commence".BBC News. 1 October 2008. Retrieved27 August2023.

- ^"MoD sells off sites in Bath for housing".BBC News. 30 March 2013. Retrieved27 August2023.

- ^RotorkHead Office Contact Details

- ^abcd"Bath in Focus".Business Matters. Archived fromthe originalon 1 March 2012. Retrieved12 December2007.

- ^"Economic Profile".Bath and North East Somerset. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 1 March 2012. Retrieved21 November2009.

- ^"AA-listed five-star hotels".Caterer Search.Archivedfrom the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved3 May2015.

- ^"Welcome". Thermae Bath Spa.Archivedfrom the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Google Street View Awards 2010".Archivedfrom the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved8 March2010.

- ^"The Shambles, York, named Britain's 'most picturesque'".BBC News. 8 March 2010.Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved8 March2010.

- ^"City of Bath World Heritage Site Management Plan – Appendix 3".Bath and North East Somerset Council. Archived fromthe originalon 4 August 2007. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Bath Abbey".Images of England. Historic England. Archived fromthe originalon 28 April 2015. Retrieved4 May2015.

- ^"A Building of Vertue".Bath Past.Archivedfrom the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved2 May2015.

- ^"Bath Abbey".Planet Ware.Archivedfrom the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved9 December2007.

- ^"Bath Abbey".Sacred destinations.Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2009. Retrieved27 September2007.