Wellington

|

Wellington

Te Whanganui-a-Tara

(Māori)

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Nickname(s):

Windy Wellington,

Wellywood

|

|

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates:41°17′20″S174°46′38″E / 41.28889°S 174.77722°E | |

| Country | New Zealand |

| Region | Wellington |

| Wards |

|

| Community boards | |

| Settled by Europeans | 1839 |

| Named for | Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington |

| Electorates | Mana Ōhāriu Rongotai Te Tai Hauāuru(Māori) Te Tai Tonga(Māori) Wellington Central[5] |

| Government | |

| •Mayor | Tory Whanau |

| •Deputy Mayor | Laurie Foon[6] |

| • MPs | |

| •Territorial authority | Wellington City Council |

| Area | |

| • Territorial | 289.91 km2(111.93 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 112.36 km2(43.38 sq mi) |

| • Rural | 177.55 km2(68.55 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 303.00 km2(116.99 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 495 m (1,624 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population

(June 2023)

[9]

|

|

| •Urban | 215,200 |

| • Urban density | 1,900/km2(5,000/sq mi) |

| •Metro | 440,900 |

| • Metro density | 1,500/km2(3,800/sq mi) |

| •Demonym | Wellingtonian |

| GDP | |

| • Metro | NZ$44.987 billion (2021) |

| • Per capita | NZ$ 82,772 (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+12(NZST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+13(NZDT) |

| Postcode(s) |

5016, 5028, 6011, 6012, 6021, 6022, 6023, 6035, 6037, 6972

[11]

|

| Area code | 04 |

| Localiwi | Ngāti Toa Rangatira,Ngāti Raukawa,Te Āti Awa |

| Website | wellington wellingtonnz.com |

Wellington[b]isthe capital cityofNew Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of theNorth Island, betweenCook Straitand theRemutaka Range. Wellington is thethird-largest cityin New Zealand,[c]and is the administrative centre of theWellington Region. It is theworld's southernmost capitalof asovereign state.[14]Wellington features a temperate maritime climate, and is the world's windiest city by averagewind speed.[15]

Māori oral tradition tells thatKupediscovered and explored the region in about the 10th century. The area was initially settled byMāoriiwisuch asRangitāneandMuaūpoko. The disruptions of theMusket Warsled to them being overwhelmed by northern iwi such asTe Āti Awaby the early 19th century.[16]

Wellington's current form was originally designed by CaptainWilliam Mein Smith, the first Surveyor General forEdward Wakefield'sNew Zealand Company, in 1840.[17]Smith's plan included a series of interconnectedgrid plans, expanding along valleys and lower hill slopes.[18]The Wellingtonurban area, which only includes urbanised areas within Wellington City, has a population of 215,200 as of June 2023.[9]The wider Wellingtonmetropolitan area, including the cities ofLower Hutt,PoriruaandUpper Hutt, has a population of 440,900 as of June 2023.[9]The city has served asNew Zealand's capitalsince 1865, a status that is not defined in legislation, but established by convention; theNew Zealand GovernmentandParliament, theSupreme Courtand most of the public service are based in the city.[19]

Wellington's economy is primarilyservice-based, with an emphasis on finance, business services, government, and the film industry. It is the centre of New Zealand'sfilmand special effects industries, and increasingly a hub for information technology and innovation,[20]with two public research universities. Wellington is one of New Zealand's chief seaports and serves both domestic and international shipping. The city is chiefly served byWellington International AirportinRongotai, the country'sthird-busiest airport. Wellington's transport network includestrain and bus lineswhich reach as far as the Kāpiti Coast andthe Wairarapa, and ferries connect the city to theSouth Island.

Often referred to as New Zealand's cultural capital, the culture of Wellington is a diverse and often youth-driven one which has wielded influence acrossOceania.[21][22][23]One of theworld's most liveable cities, the 2021Global Livability Rankingtied Wellington withTokyoas fourth in the world.[24]From 2017 to 2018,Deutsche Bankranked it first in the world for both livability and non-pollution.[25][26]Cultural precincts such asCuba StreetandNewtownare renowned for creative innovation, "op shops", historic character, andfood. Wellington is a leadingfinancial centrein theAsia-Pacificregion, being ranked35th in the worldby theGlobal Financial Centres Indexfor 2021. Theglobal cityhas grown from a bustling Māori settlement, to a colonial outpost, and from there to anAustralasiancapital that has experienced a "remarkable creative resurgence".[27][28][29][30]

Toponymy

[edit]Wellington takes its name fromArthur Wellesley, the firstDuke of Wellingtonand victor of theBattle of Waterloo(1815): his title comes from the town ofWellingtonin theEnglish countyofSomerset. It was named in November 1840 by the original settlers of theNew Zealand Companyon the suggestion of the directors of the same, in recognition of the Duke's strong support for the company's principles of colonisation and his "strenuous and successful defence against its enemies of the measure for colonising South Australia". One of the founders of the settlement,Edward Jerningham Wakefield, reported that the settlers "took up the views of the directors with great cordiality and the new name was at once adopted".[31]

In theMāori language, Wellington has three names:

- Te Whanganui-a-Tara, meaning "the great harbour of Tara", refers toWellington Harbour.[32]The primary settlement of Wellington is said to have been executed by Tara, the son ofWhatonga, a chief from theMāhia Peninsula, who told his son to travel south, to find more fertile lands to settle.[33]

- Pōneke, commonly held to be a phonetic Māori transliteration of "Port Nick", short for "Port Nicholson".[34]An alternatively suggested etymology forPōnekeis that it comes from a shortening of the phrasePō Nekeneke, meaning "journey into the night", referring to the exodus ofTe Āti Awafrom the Wellington area after they were displaced by the first European settlers.[35][36][37]However, the name Pōneke was already in use by February 1842,[38]earlier than the displacement is said to have happened. The city's centralmarae, the community supporting it and itskapa hakagroup have the pseudo-tribal name ofNgāti Pōneke.[39]

- Te Upoko-o-te-Ika-a-Māui, meaning "The Head of the Fish of Māui" (often shortened toTe Upoko-o-te-Ika), a traditional name for the southernmost part of the North Island, deriving from the legend of the fishing up of the island by the demi-godMāui.

The legendary Māori explorerKupe, a chief fromHawaiki(the homeland of Polynesian explorers, of unconfirmed geographical location, not to be confused withHawaii), was said to have stayed in the harbour prior to 1000 CE.[33]Here, it is said he had a notable impact on the area, with local mythology stating he named the two islands in the harbour after his daughters,Matiu (Somes Island), andMākaro (Ward Island).[40]

InNew Zealand Sign Language, the name is signed by raising the index, middle, and ring fingers of one hand, palm forward, to form a "W", and shaking it slightly from side to side twice.[41]

The city's location close to the mouth of the narrow Cook Strait leaves it vulnerable to strong gales, leading to thenicknameof "Windy Wellington".[42]

History

[edit]Māori settlement

[edit]

Legends recount thatKupediscovered and explored the region in about the 10th century. Before European colonisation, the area in which the city of Wellington would eventually be founded was seasonally inhabited by indigenousMāori. The earliest date with hard evidence for human activity in New Zealand is about 1280.[43]

Wellington and its environs have been occupied by various Māori groups from the 12th century. The legendary Polynesian explorer Kupe, a chief fromHawaiki(the homeland of Polynesian explorers, of unconfirmed geographical location, not to be confused withHawaii), was said to have stayed in the harbour fromc. 925.[44][45]A later Māori explorer, Whatonga, named the harbourTe Whanganui-a-Taraafter his son Tara.[46]Before the 1820s, most of the inhabitants of the Wellington region were Whatonga's descendants.[47]

At about 1820, the people living there were Ngāti Ira and other groups who traced their descent from the explorer Whatonga, includingRangitāneandMuaūpoko.[16]However, these groups were eventually forced out ofTe Whanganui-a-Taraby a series of migrations by otheriwi(Māori tribes) from the north.[16]The migrating groups wereNgāti Toa, which came fromKāwhia, Ngāti Rangatahi, from nearTaumarunui, andTe Ātiawa,Ngāti Tama,Ngāti Mutunga, Taranaki andNgāti RuanuifromTaranaki. Ngāti Mutunga later moved on to theChatham Islands. TheWaitangi Tribunalhas found that at the time of the signing of theTreaty of Waitangiin 1840, Te Ātiawa, Taranaki, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāti Tama, and Ngāti Toa heldmana whenuainterests in the area, through conquest and occupation.[16]

Early European settlement

[edit]

Steps towardsEuropean settlementin the area began in 1839, when ColonelWilliam Wakefieldarrived to purchase land for theNew Zealand Companyto sell to prospectiveBritishsettlers.[16]Prior to this time, the Māori inhabitants had had contact with Pākehā whalers and traders.[48]

European settlement began with the arrival of an advance party of the New Zealand Company on the shipToryon 20 September 1839, followed by 150 settlers on theAuroraon 22 January 1840. Thus, the Wellington settlement preceded the signing of theTreaty of Waitangi(on 6 February 1840). The 1840 settlers constructed their first homes atPetone(which they called Britannia for a time) on the flat area at the mouth of theHutt River. Within months that area proved swampy and flood-prone, and most of the newcomers transplanted their settlement across Wellington Harbour toThorndonin the present-day site of Wellington city.[49]

National capital

[edit]

Wellington was declared a city in 1840, and was chosen to be the capital city of New Zealand in1865.[19]

Wellington became the capital city in place ofAuckland, whichWilliam Hobsonhad made the capital in1841. TheNew Zealand Parliamenthad first met in Wellington on 7 July 1862, on a temporary basis; in November 1863, thePrime Minister of New Zealand,Alfred Domett, placed a resolution before Parliament in Auckland that "... it has become necessary that theseat of government... should be transferred to some suitable locality inCook Strait[region]." There had been some concerns that the more populousSouth Island(where the goldfields were located) would choose to form a separate colony in theBritish Empire. Several commissioners (delegates) invited from Australia, chosen for their neutral status, declared that the city was a suitable location because of its central location in New Zealand and its goodharbour; it was believed that the wholeRoyal Navyfleet could fit into the harbour.[50]Wellington's status as the capital is a result ofconstitutional conventionrather than statute.[19]

Wellington is New Zealand'spoliticalcentre, housing the nation's major government institutions. The New Zealand Parliament relocated to the new capital city, having spent the first ten years of its existence in Auckland.[51]A session of parliament officially met in the capital for the first time on 26 July 1865. At that time, the population of Wellington was just 4,900.[52]

TheGovernment Buildingswere constructed atLambton Quayin 1876. The site housed the originalgovernment departments in New Zealand. The public service rapidly expanded beyond the capacity of the building, with the first department leaving shortly after it was opened; by 1975 only the Education Department remained, and by 1990 the building was empty. The capital city is also the location of the highest court, theSupreme Court of New Zealand, and the historic former High Court building (opened 1881) has been enlarged and restored for its use. The Governor-General's residence,Government House(the current building completed in 1910) is situated inNewtown, opposite theBasin Reserve.Premier House(built in 1843 for Wellington's first mayor,George Hunter), the official residence of theprime minister, is inThorndonon Tinakori Road.

Over six months in 1939 and 1940, Wellington hosted theNew Zealand Centennial Exhibition, celebrating a century since the signing of theTreaty of Waitangi. Held on 55 acres of land at Rongotai, it featured three exhibition courts, grand Art Deco-style edifices and a hugely popular three-acre amusement park. Wellington attracted more than 2.5 million visitors at a time when New Zealand's population was 1.6 million.[53]

Geography

[edit]

Wellington is at the south-western tip of theNorth IslandonCook Strait, separating the North and South Islands. On a clear day, the snowcappedKaikōura Rangesare visible to the south across the strait. To the north stretch the golden beaches of theKāpiti Coast. On the east, theRemutaka Rangedivides Wellington from the broad plains of theWairarapa, awine regionof national notability.

With alatitudeof 41° 17' South, Wellington is thesouthernmost capital city in the world.[54]Wellington ties withCanberra, Australia, as themost remotecapital city, 2,326 km (1,445 mi) apart from each other.

Wellington is more densely populated than most other cities in New Zealand due to the restricted amount of land that is available between its harbour and the surrounding hills. It has very few open areas in which to expand, and this has brought about the development of the suburban towns. Because of its location in theRoaring Fortiesand its exposure to the winds blowing throughCook Strait, Wellington is the world's windiest city, with an average wind speed of 27 km/h (17 mph).[55]

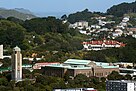

Wellington's scenic natural harbour and green hillsides adorned with tiered suburbs of colonial villas are popular with tourists. The central business district (CBD) is close to Lambton Harbour, an arm ofWellington Harbour, which lies along an activegeological fault, clearly evident on its straight western shore. The land to the west of this rises abruptly, meaning that many suburbs sit high above the centre of the city. There is a network of bush walks and reserves maintained by theWellington City Counciland local volunteers. These includeOtari-Wilton's Bush, dedicated to the protection and propagation of native plants. The Wellington region has 500 square kilometres (190 sq mi) of regional parks and forests. In the east is theMiramar Peninsula, connected to the rest of the city by a low-lying isthmus atRongotai, the site ofWellington International Airport. Industry has developed mainly in the Hutt Valley, where there are food-processing plants, engineering industries, vehicle assembly and oil refineries.[56]

The narrow entrance to the harbour is to the east of the Miramar Peninsula, and contains the dangerous shallows ofBarrett Reef, where many ships have been wrecked (notably the inter-island ferryTEVWahinein1968).[57]The harbour has three islands:Matiu/Somes Island,Makaro/Ward IslandandMokopuna Island. Only Matiu/Somes Island is large enough for habitation. It has been used as a quarantine station for people and animals, and was aninternment campduring World War I and World War II. It is a conservation island, providing refuge forendangered species, much likeKapiti Islandfarther up the coast. There is access during daylight hours by the Dominion Post Ferry.

Wellington is primarily surrounded by water, but some of the nearby locations are listed below.

Geology

[edit]Wellington suffered serious damage in a series ofearthquakes in 1848[58]and from another earthquake in 1855. The1855 Wairarapa earthquakeoccurred on theWairarapa Faultto the north and east of Wellington. It was probably the most powerful earthquake in recorded New Zealand history,[59]with an estimated magnitude of at least 8.2 on theMoment magnitude scale. It caused vertical movements of two to three metres over a large area, including raising land out of the harbour and turning it into a tidal swamp. Much of this land was subsequentlyreclaimedand is now part of the central business district. For this reason, the street namedLambton Quayis 100 to 200 metres (325 to 650 ft) from the harbour – plaques set into the footpath mark the shoreline in1840, indicating the extent of reclamation. The1942 Wairarapa earthquakescaused considerable damage in Wellington.

The area has high seismic activity even by New Zealand standards, with a major fault, theWellington Fault, running through the centre of the city and several others nearby. Several hundred minor faults lines have been identified within the urban area. Inhabitants, particularly in high-rise buildings, typically notice several earthquakes every year. For many years after the 1855 earthquake, the majority of buildings were made entirely from wood. The 1996-restoredGovernment Buildings[60]near Parliament is the largest wooden building in the Southern Hemisphere. While masonry andstructural steelhave subsequently been used in building construction, especially for office buildings,timber framingremains the primary structural component of almost all residential construction. Residents place their confidence in goodbuilding regulations, which became more stringent in the 20th century. Since the Canterbury earthquakes of2010and2011, earthquake readiness has become even more of an issue, with buildings declared byWellington City Councilto be earthquake-prone,[61][62]and the costs of meeting new standards.[63][64]

Every five years, a year-long slow quake occurs beneath Wellington, stretching from Kapiti to theMarlborough Sounds. It was first measured in 2003, and reappeared in 2008 and 2013.[65]It releases as much energy as a magnitude 7 quake, but as it happens slowly, there is no damage.[66]

During July and August 2013 there were many earthquakes, mostly in Cook Strait near Seddon. The sequence started at 5:09 pm on Sunday 21 July 2013 when the magnitude 6.5Seddon earthquakehit the city, but no tsunami report was confirmed nor any major damage.[67]At 2:31 pm on Friday 16 August 2013 theLake Grassmere earthquakestruck, this time magnitude 6.6, but again no major damage occurred, though many buildings were evacuated.[68]On Monday 20 January 2014 at 3:52 pma rolling 6.2 magnitude earthquakestruck the lower North Island 15 km east ofEketāhunaand was felt in Wellington, but little damage was reported initially, except atWellington Airportwhere one of the two giant eagle sculptures commemoratingThe Hobbitbecame detached from the ceiling.[69][70]

At two minutes after midnight on Monday 14 November 2016, the 7.8 magnitudeKaikōura earthquake, which was centred between Culverden and Kaikōura in the South Island, caused the Wellington CBD,Victoria University of Wellington, and theWellington suburban rail networkto be largely closed for the day to allow inspections. The earthquake damaged a considerable number of buildings, with 65% of the damage being in Wellington. Subsequently, a number of recent buildings were demolished rather than being rebuilt, often a decision made by the insurer. Two of the buildings demolished were about eleven years old – the seven-storeyNZDFheadquarters[71][72]and Statistics House at Centreport on the waterfront.[73]The docks were closed for several weeks after the earthquake.[74]

Relief

[edit]Steep landforms shape and constrain much of Wellington city. Notable hills in and around Wellington include:

- Mount Victoria– 196 m. Mt Vic is a popular walk for tourists and Wellingtonians alike, as from the summit one can see most of Wellington. There are numerous mountain bike and walking tracks on the hill.

- Mount Albert[75]– 178 m

- Mount Cook

- Mount Alfred (west of Evans Bay)[76]– 122 m

- Mount Kaukau– 445 m. Site of Wellington's main television transmitter.

- Mount Crawford[77]

- Brooklyn Hill – 299 m

- Wrights Hill

- Mākara Peak – summit (412m) is within the 250haMakara Peak Mountain Bike Parkthat includes 45km of trails[78]

- Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori) Hill

Climate

[edit]Averaging 2,055 hours of sunshine per year, the climate of Wellington is temperatemarine, (Köppen:Cfb), generally moderate all year round with warm summers and mild winters, and rarely sees temperatures above 26 °C (79 °F) or below 4 °C (39 °F). The hottest recorded temperature in the city is 31.1 °C (88 °F) recorded on 20 February 1896[citation needed], while −1.9 °C (29 °F) is the coldest.[79]The city is notorious for its southerly blasts in winter, which may make the temperature feel much colder. It is generally very windy all year round with high rainfall; average annual rainfall is 1,250 mm (49 in), June and July being the wettest months.Frostsare quite common in the hill suburbs and theHutt Valleybetween May and September. Snow is very rare at low altitudes, although snow fell on the city and many other parts of the Wellington region during separateeventson 25 July 2011 and 15 August 2011.[80][81]Snow at higher altitudes is more common, with light flurries recorded in higher suburbs every few years.[82]

On 29 January 2019, the suburb of Kelburn (instruments near theMetservicebuilding in theWellington Botanic Garden) reached 30.3 °C (87 °F), the highest temperature since records began in 1927.[83]

| Climate data for Wellington (Kelburn) (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1862–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.3 (86.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

22.0 (71.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

29.1 (84.4) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 26.1 (79.0) |

25.3 (77.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

20.8 (69.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.3 (68.5) |

20.6 (69.1) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.7 (62.1) |

14.6 (58.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

12.4 (54.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

9.7 (49.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

6.7 (44.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 8.6 (47.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.9 (37.2) |

2.5 (36.5) |

2.6 (36.7) |

3.1 (37.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.7 (45.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.1 (39.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

1.1 (34.0) |

1.7 (35.1) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 79.2 (3.12) |

55.5 (2.19) |

99.6 (3.92) |

126.7 (4.99) |

144.9 (5.70) |

123.8 (4.87) |

147.1 (5.79) |

139.1 (5.48) |

108.0 (4.25) |

118.7 (4.67) |

85.4 (3.36) |

91.1 (3.59) |

1,319.1 (51.93) |

| Average rainy days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.9 | 6.9 | 9.3 | 10.3 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 12.8 | 12.5 | 10.9 | 12.4 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 128.2 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 78.3 | 80.0 | 82.2 | 81.8 | 83.7 | 85.5 | 84.6 | 82.9 | 78.9 | 79.7 | 78.0 | 78.4 | 81.2 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 231.8 | 211.4 | 204.0 | 156.4 | 133.1 | 101.2 | 121.0 | 147.8 | 164.4 | 193.3 | 211.7 | 218.0 | 2,094.1 |

| Source: NIWA[84][85][86] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data forParaparaumu(2000–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Averageultraviolet index | 11 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 6 |

| Source: NIWA[87] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data forWellington International Airport(1991–2020 normals, extremes 1962–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 29.6 (85.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

28.3 (82.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

26.8 (80.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 26.0 (78.8) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.6 (70.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 21.0 (69.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

12.5 (54.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.6 (67.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.8 (64.0) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.6 (51.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

10.3 (50.5) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

16.5 (61.7) |

13.8 (56.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.6 (58.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

13.5 (56.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

8.0 (46.4) |

7.1 (44.8) |

7.6 (45.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.9 (51.7) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 9.9 (49.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.6 (36.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

1.0 (33.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

4.5 (40.1) |

4.3 (39.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 60.0 (2.36) |

60.4 (2.38) |

66.0 (2.60) |

79.8 (3.14) |

88.4 (3.48) |

102.6 (4.04) |

109.7 (4.32) |

94.1 (3.70) |

79.9 (3.15) |

90.9 (3.58) |

74.7 (2.94) |

67.1 (2.64) |

973.6 (38.33) |

| Average rainy days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.6 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 8.2 | 10.2 | 12.3 | 12.0 | 12.4 | 10.6 | 10.3 | 8.4 | 8.1 | 113.0 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 75.1 | 76.8 | 77.6 | 78.0 | 80.0 | 81.5 | 81.0 | 80.0 | 76.5 | 75.4 | 73.6 | 74.9 | 77.5 |

| Source: NIWA[87][88] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

Wellington City covers 289.91 km2(111.93 sq mi)[89]and had an estimated population of 216,200 as of June 2023,[9]with a population density of 746 people per km2. This comprises 215,200 people in the Wellingtonurban areaand 1,000 people in the surrounding rural areas.[9]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 179,466 | — |

| 2013 | 190,956 | +0.89% |

| 2018 | 202,737 | +1.20% |

| 2023 | 202,689 | −0.00% |

| Source:[90][91] | ||

Wellington City had a population of 202,689 in the2023 New Zealand census, a decrease of 48 people (−0.0%) since the2018 census, and an increase of 11,733 people (6.1%) since the2013 census. There were 84,990 dwellings. The median age was 34.9 years (compared with 38.1 years nationally). There were 29,142 people (14.4%) aged under 15 years, 55,083 (27.2%) aged 15 to 29, 94,803 (46.8%) aged 30 to 64, and 23,670 (11.7%) aged 65 or older.[91]

Wellington City had a population of 202,737 at the2018 New Zealand census. There were 74,841 households, comprising 98,823 males and 103,911 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.95 males per female.

Of those at least 15 years old, 74,922 (44.1%) people had a bachelor's or higher degree, and 12,690 (7.5%) people had no formal qualifications. The median income was $41,800, compared with $31,800 nationally. 48,633 people (28.6%) earned over $70,000 compared to 17.2% nationally. The employment status of those at least 15 was that 96,453 (56.8%) people were employed full-time, 24,738 (14.6%) were part-time, and 7,719 (4.5%) were unemployed.[90]

| Name | Area (km2) | Population | Density (per km2) | Households | Median age | Median income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Ward | 102.22 | 47,796 | 468 | 16,467 | 35.9 years | $41,500 |

| Onslow-Western Ward | 136.22 | 43,176 | 317 | 15,750 | 38.6 years | $51,800 |

| Lambton Ward | 12.91 | 46,140 | 3,574 | 18,204 | 28.4 years | $37,500 |

| Eastern Ward | 16.20 | 37,965 | 2,344 | 14,199 | 37.0 years | $41,100 |

| Southern Ward | 22.22 | 27,654 | 1,245 | 10,221 | 34.0 years | $38,700 |

| New Zealand | 37.4 years | $31,800 |

Quality of living

[edit]

Wellington ranks 12th in the world for quality of living,[25]according to a 2014 study by consulting company Mercer; of cities in the Asia–Pacific region, Wellington ranked third behind Auckland and Sydney (as of 2014[update]).[25]

In 2009, Wellington was ranked as a highly affordable city in terms ofcost of living, coming in at 139th most expensive city out of 143 cities in the Mercer worldwide Cost of Living Survey.[92]Between 2009 and 2020 the cost of living in Wellington increased, and it is now ranked 123rd most expensive city out of a total of 209 cities.[93]

Culture and identity

[edit]In addition to governmental institutions, Wellington accommodates several of the nation's largest and oldest cultural institutions, such as theNational Archives, theNational Library, New Zealand's national museum,Te Papaand numerous theatres. It plays host to many artistic and cultural organisations, including theNew Zealand Symphony OrchestraandRoyal New Zealand Ballet. Its architectural attractions include theOld Government Buildings– one of the largest wooden buildings in the world – as well as the iconicBeehive, the executive wing ofParliament Buildingsas well as internationally renownedFutuna Chapel. The city's art scene includes many art galleries, including the national art collection at Toi Art at Te Papa.[94]Wellington also has many events such asCubaDupa,Wellington On a Plate, theNewtown Festival, Diwali Festival of Lights and Gardens Magic at the Botanical Gardens.[95][96][97]

At the 2018 census, English is the most spoken language (96.0%) followed by French (3.2%), Te Reo Māori (2.2%), Mandarin (2.0%) and German (2.0%). Percentages add up to more than 100% as people may select more than one language.

Although some people chose not to answer the census's question about religious affiliation, 53.2% had no religion, 31.4% wereChristian, 0.4% hadMāori religious beliefs, 3.7% wereHindu, 1.6% wereMuslim, 1.7% wereBuddhistand 3.0% had other religions.[90]

At the 2018 Census, 33.4% of Wellington's population was born overseas, compared with 27.1% nationally.[90]The most common birthplaces of overseas-born residents were England (6.2%), India (3.1%), mainland China (2.6%), Australia (2.0%), the Philippines (1.7%), the United States (1.5%), and South Africa (1.2%).[90]

In the 2023 census, ethnicities were 72.1% European/Pākehā, 9.8%Māori, 5.7%Pasifika, 20.4%Asian, 3.6% Middle Eastern, Latin American and African New Zealanders, and 1.1% other. People may identify with more than one ethnicity.[91]

| Ethnicity | 2006 census | 2013 census | 2018 census | 2023 census | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| European | 121,296 | 70.1 | 139,107 | 76.4 | 150,198 | 74.1 | 146,208 | 72.1 |

| Māori | 13,335 | 7.7 | 14,433 | 7.9 | 17,409 | 8.6 | 19,878 | 9.8 |

| Pacific peoples | 8,931 | 5.2 | 8,928 | 4.9 | 10,392 | 5.1 | 11,565 | 5.7 |

| Asian | 22,851 | 13.2 | 28,542 | 15.7 | 37,158 | 18.3 | 41,436 | 20.4 |

| Middle Eastern/Latin American/African | 3,615 | 2.1 | 4,494 | 2.5 | 6,135 | 3.0 | 7,356 | 3.6 |

| Other | 18,384 | 10.6 | 3,351 | 1.8 | 2,892 | 1.4 | 2,166 | 1.1 |

| Total people stated | 172,971 | 182,121 | 202,737 | 202,689 | ||||

| Not elsewhere included | 6,492 | 3.8 | 8,835 | 4.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Architecture

[edit]

Wellington showcases a variety of architectural styles from the past 150 years – 19th-century wooden cottages, such as theItalianateKatherine Mansfield Birthplacein Thorndon; streamlinedArt Decostructures such as the oldWellington Free Ambulanceheadquarters, the Central Fire Station, Fountain Court Apartments, theCity Gallery, and theformer Post and Telegraph Building; and the curves and vibrant colours of post-modern architecture in the CBD.

The oldest building is the 1858Nairn Street CottageinMount Cook.[99]The tallest building is theMajestic Centreon Willis Street at 116 metres high, the second-tallest being thestructural expressionistAon Centre (Wellington)at 103 metres.[100]Futuna ChapelinKaroriis an iconic building designed by Māori architect John Scott and is architecturally considered one of the most significant New Zealand buildings of the 20th century.[101]

Old St Paul'sis an example of 19th-centuryGothic Revival architectureadapted to colonial conditions and materials, as isSt Mary of the Angels.Sacred Heart Cathedralis aPalladian RevivalBasilicawith thePorticoof aRoman or Greek temple. TheMuseum of Wellington City & Seain theBond Storeis in theSecond French Empirestyle, and theWellington Harbour Board Wharf Office Buildingis in a late English Classical style. There are several restored theatre buildings: theSt James Theatre, theOpera Houseand theEmbassy Theatre.

Te Ngākau Civic Squareis surrounded by theTown Halland council offices, theMichael Fowler Centre, theWellington Central Library, theCity-to-Sea Bridge, and theCity Gallery.

As it is the capital city, there are many notable government buildings. The Executive Wing ofNew Zealand Parliament Buildings, on the corner of Lambton Quay and Molesworth Street, was constructed between 1969 and 1981 and is commonly referred to asthe Beehive. Across the road is the largest wooden building in theSouthern Hemisphere,[102]part of theold Government Buildingswhich now houses part ofVictoria University of Wellington's Law Faculty.

A modernist building housing theMuseum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewalies on the waterfront, on Cable Street. It is strengthened usingbase isolation[103]– essentially seating the entire building on supports made from lead, steel and rubber that slow down the effect of an earthquake.

Other notable buildings includeWellington Town Hall,Wellington railway station,Dominion Museum(nowMassey University),Aon Centre (Wellington),Wellington Regional Stadium, andWellington AirportatRongotai. Leading architects includeFrederick Thatcher,Frederick de Jersey Clere,W. Gray Young,Bill Alington,Ian Athfield,Roger Walker.

Wellington contains many iconic sculptures and structures, such asthe Bucket FountaininCuba StreetandInvisible CitybyAnton Parsonson Lambton Quay. Kinetic sculptures have been commissioned, such as theZephyrometer.[104]This 26-metre orange spike built for movement by artist Phil Price has been described as "tall, soaring and elegantly simple", which "reflects the swaying of the yacht masts in the Evans Bay Marina behind it" and "moves like the needle on the dial of a nautical instrument, measuring the speed of the sea or wind or vessel."[105]

Wellington has many different architectural styles, such as classicPainted LadiesinMount Victoria,NewtownandOriental Bay, WoodenArt Decohouses spread throughout (especially further north in theHutt Valley), the classic masonry buildings in Cuba Street,state housesparticularly in the Hutt and Wellington's southern suburbs,railway housesinNgaioand other railway-side suburbs, large modern buildings in the city centre (such as the distinctive skyscraper called theMajestic Centre) and grand Victorian buildings common in the inner city as well.

Housing and real estate

[edit]

House prices

[edit]Historic

[edit]Wellington experienced a real estate boom in the early 2000s and the effects of the international property bust at the start of 2007. In 2005, the market was described as "robust".[106]By 2008, property values had declined by about 9.3% over a 12-month period, according to one estimate. More expensive properties declined more steeply, sometimes by as much as 20%.[107]"From 2004 to early 2007, rental yields were eroded and positive cash flow in property investments disappeared as house values climbed faster than rents. Then that trend reversed and yields slowly began improving", according to twoThe New Zealand Heraldreporters writing in May 2009.[108]In the middle of 2009, house prices had dropped, interest rates were low, and buy-to-let property investment was again looking attractive, particularly in the Lambton precinct, according to these two reporters.[108]

Current

[edit]Since 2009, house prices in Wellington have increased significantly. In May 2021, the Real Estate Institute of New Zealand (REINZ) reported the median house price was $1,057,000 in Wellington City, $930,000 in Porirua, $873,500 in Lower Hutt and $828,000 in Upper Hutt, compared to a national median house price of $820,000.[109]The substantial increase in house prices has made it difficult for first home buyers to purchase a home in the city and is also credited with pushing up the house prices in neighbouring cities like Porirua.[110]Housing costs have been identified making it difficult for some professions, like nurses, to afford to live in Wellington.[111][112]The median rent in Wellington has also increased significantly in recent years to $600 per week, higher even than Auckland.[113]

Housing quality

[edit]Despite the high cost of housing in the capital, the quality of housing in Wellington has been criticised as being poor. 18.4% of houses in Wellington City are sometimes or always mouldy and 24% are sometimes or always damp.[114]Both of these are higher than the New Zealand average.

Demographics

[edit]

A Wellington City Council survey conducted in March 2009 found the typical central city apartment dweller was a New Zealand native aged 24 to 35 with a professional job in the downtown area, with household income higher than surrounding areas.[115]Three-quarters (73%) walked to work or university, 13% travelled by car, 6% by bus, 2% bicycled (although 31% own bicycles), and did not travel very far since 73% worked or studied in the central city.[115]The large majority (88%) did not have children in their apartments; 39% were couples without children; 32% were single-person households; 15% were groups of people flatting together.[115]Most (56%) owned their apartment; 42% rented.[115]The report continued: "The four most important reasons for living in an apartment were given as lifestyle and city living (23%), close to work (20%), close to shops and cafes (11%) and low maintenance (11%) ... City noise and noise from neighbours were the main turnoffs for apartment dwellers (27%), followed by a lack of outdoor space (17%), living close to neighbours (9%) and apartment size and a lack of storage space (8%)."[115][116]

Households are primarily one-family, making up 66.9% of households, followed by single-person households (24.7%); there were fewer multiperson households and even fewer households containing two or more families. These counts are from the 2013 census for the Wellington region (which includes the surrounding area in addition to the four cities).[117]

Economy

[edit]

Wellington Harbourranks as one of New Zealand's chief seaports and serves both domestic and international shipping. The port handles approximately 10.5 million tonnes of cargo on an annual basis,[118]importing petroleum products, motor vehicles, minerals and exporting meats, wood products, dairy products, wool, and fruit. Manycruise shipsalso use the port.

The Government sector has long been a mainstay of the economy, which has typically risen and fallen with it. Traditionally, its central location meant it was the location of many head offices of various sectors – particularly finance, technology and heavy industry – many of which have since relocated to Auckland following economic deregulation and privatisation.[119][120]

In recent years, tourism, arts and culture, film, andICThave played a bigger role in the economy. Wellington's median income is well above the average in New Zealand,[121]and the highest of all New Zealand cities.[122]It has a much higher proportion of people with tertiary qualifications than the national average.[123]Major companies with their headquarters in Wellington include:

At the 2013 census, the largest employment industries for Wellington residents were professional, scientific and technical services (25,836 people), public administration and safety (24,336 people), health care and social assistance (17,446 people), education and training (16,550 people) and retail trade (16,203 people).[124]In addition, Wellington is an important centre of the New Zealand film and theatre industry, and second to Auckland in terms of numbers of screen industry businesses.[125]

Tourism

[edit]

Tourismis a major contributor to the city's economy, injecting approximately NZ$1.3 billion into the region annually and accounting for 9% of total FTE employment.[126]The city is consistently named as New Zealanders' favourite destination in the quarterly FlyBuys Colmar Brunton Mood of the Traveller survey[127]and it was ranked fourth inLonely PlanetBest in Travel 2011's Top 10 Cities to Visit in 2011.[128]New Zealanders make up the largest visitor market, with 3.6 million visits each year; New Zealand visitors spend on average NZ$2.4 million a day.[129]There are approximately 540,000 international visitors each year, who spend 3.7 million nights and NZ$436 million. The largest international visitor market is Australia, with over 210,000 visitors, spending approximately NZ$334 million annually.[130]It has been argued that the construction of theTe Papamuseum helped transform Wellington into a tourist destination.[131]Wellington is marketed as the 'coolest little capital in the world' by Positively Wellington Tourism, an award-winning regional tourism organisation[132]set up as a council controlled organisation by Wellington City Council in 1997.[133]The organisation's council funding comes through the Downtown Levy commercial rate.[134]In the decade to 2010, the city saw growth of over 60% in commercial guest nights. It has been promoted through a variety of campaigns and taglines, starting with the iconic Absolutely Positively Wellington advertisements.[135]The long-term domestic marketing strategy was a finalist in the 2011 CAANZ Media Awards.[136]

Popular tourist attractions includeWellington Museum,Wellington Zoo,ZealandiaandWellington Cable Car.Cruise tourismis experiencing a major boom in line with nationwide development. The 2010/11 season saw 125,000 passengers and crew visits on 60 liners. There were 80 vessels booked for visits in the 2011/12 season – estimated to inject more than NZ$31 million into the economy and representing a 74% increase in the space of two years.[137]

Wellington is a popular conference tourism destination due to its compact nature, cultural attractions, award-winning restaurants and access to government agencies. In the year ending March 2011, there were 6,495 conference events involving nearly 800,000 delegate days; this injected approximately NZ$100 million into the economy.[138]

Arts and culture

[edit]Culture

[edit]

Owing to the work of Positively Wellington Tourism in marketing it as "the coolest little capital",[132]the city has been injected into the global zeitgeist as exactly that.[139]It has been traditionally acclaimed as New Zealand's "cultural and creative capital".[140][141][142]The city is known for its coffee scene, with now-globally common foods and drinks such as theflat whiteperfected here.[143][144]Wellington has a strong coffee culture – the city has more cafés per capita thanNew York City– and was pioneered byItalianandGreekimmigrants to areas such asMount Victoria,Island BayandMiramar.[145]Nascent influence is derived fromEthiopianmigrants. Wellington's cultural vibrance and diversity is well-known across the world. It is New Zealand's second most ethnically diverse city, bested only by Auckland, and boasts a "melting pot" culture of significant minorities such asMalaysian,[146]Italian,Dutch,Korean,Chinese,Greek,[147]Indian,Samoanand indigenousTaranaki Whānuicommunities as a result. In particular, Wellington is noted for is contributions to art, cuisine[148]and international filmmaking (withAvatarandThe Lord of the Ringsbeing largely produced in the city) among many other factors listed below. TheWorld of Wearable Arts(WOW) is an annual event that brings lots of visitors to Wellington every year.[149]

Museums and cultural institutions

[edit]

Wellington is home to many cultural institutions, includingTe Papa(the Museum of New Zealand), theNational Library of New Zealand,Archives New Zealand,Wellington Museum(formerly the Wellington Museum of City and Sea), theKatherine Mansfield House and Garden(formerly Katherine Mansfield Birthplace),Colonial Cottage, theWellington Cable CarMuseum, theReserve BankMuseum,Old St Paul's, theNational War Memorial[19]Ngā Taonga Sound and Vision,Capital Echildren's playspace and theWellington City Gallery.

Festivals

[edit]Wellington is home to many high-profile events and cultural celebrations, including the biennialNew Zealand Festival of the Arts, biennial Wellington Jazz Festival, biennial Capital E National Arts Festival for Children and major events such asWorld of Wearable Art,TEDxWellington,Cuba Street Carnival,Wellington On a Plate,New Zealand Fringe Festival,New Zealand International Comedy Festival, New Zealand Affordable Art Show,Out In The Square, Beervana, andHomegrown Music Festival.

The annual children'sArtsplash Festivalbrings together hundreds of students from across the region. The week-long festival includes music and dance performances and the presentation of visual arts.[150]The Performance Arcadeis an annual live-art event in shipping containers on the waterfront.[151]

Film

[edit]FilmmakersSir Peter Jackson,Sir Richard Taylorand a growing team of creative professionals have turned the eastern suburb ofMiramarinto a film-making, post-production and special effects infrastructure centre, giving rise to the moniker 'Wellywood'.[152][153]Jackson's companies includeWētā Workshop,Wētā FX, Camperdown Studios, post-production housePark Road Post, and Stone Street Studios near Wellington Airport.[154][155]Films shot partly or wholly in Wellington include theLord of The Ringstrilogy,King KongandAvatar. Jackson described Wellington: "Well, it's windy. But it's actually a lovely place, where you're pretty much surrounded by water and the bay. The city itself is quite small, but the surrounding areas are very reminiscent of the hills up in northern California, likeMarin Countynear San Francisco and the Bay Area climate and some of the architecture. Kind of a cross between that and Hawaii."[156]

Sometime Wellington directorsJane CampionandGeoff Murphyhave reached the world's screens with their independent spirit. Emerging Kiwi filmmakers, likeRobert Sarkies,Taika Waititi, Costa Botes and Jennifer Bush-Daumec,[157]are extending the Wellington-based lineage and cinematic scope. There are agencies to assist film-makers with tasks such as securing permits and scouting locations.[158]

Wellington has a large number of independent cinemas, including theEmbassy Theatre, Penthouse, the Roxy and Light House, which participate in film festivals throughout the year. Wellington has one of the country's highest turn-outs for the annualNew Zealand International Film Festival. There are a number of other film festivals hosted in Wellington, such as Doc Edge (documentary),[159]the Japanese Film Festival[160]and Show Me Shorts (short films).[161]

Music

[edit]The music scene has produced bands such asThe Warratahs,The Mockers,The Phoenix Foundation,Shihad,Beastwars,Fly My Pretties,Rhian Sheehan,Birchville Cat Motel, Black Boned Angel,Fat Freddy's Drop,The Black Seeds,Fur Patrol,Flight of the Conchords,Connan Mockasin,RhombusandModule,Weta,Demoniac, andDARTZ. TheNew Zealand School of Musicwas established in 2005 through a merger of the conservatory and theory programmes atMassey UniversityandVictoria University of Wellington.New Zealand Symphony Orchestra,Nevine String QuartetandChamber musicNew Zealand are based in Wellington. The city is also home to theRodger Fox Big Band.

Theatre and dance

[edit]Wellington is home toBATS Theatre,Circa Theatre, the national kaupapa Māori theatre companyTaki Rua, the National Theatre for Children at Capital E, theRoyal New Zealand Ballet, Gryphon Theatre, and contemporary dance companyFootnote.

Venues includeSt James' Theatreon Courtenay Place,[162]The Opera Houseon Manners Street and theHannah Playhouse.

Te WhaeaNational Dance & Drama Centre, houses New Zealand's university-level schools,Toi Whakaari: New Zealand Drama School & theNew Zealand School of Dance, these are separate entities that share the building's facilities.

Te Auaha the Whitireia Performing Arts Centreis downtown off Cuba Street.

Comedy

[edit]Many of New Zealand's prominent comedians have either come from Wellington or got their start there, such asGinette McDonald("Lyn of Tawa"),Raybon Kan,Dai Henwood,Ben Hurley, Steve Wrigley, Guy Williams, theFlight of the Conchordsand the satiristJohn Clarke("Fred Dagg").

Wellington is home to groups that perform improvised theatre andimprovisational comedy, includingWellington Improvisation Troupe(WIT).[citation needed]The comedy group Breaking the 5th Wall[163]operated out of Wellington and regularly did shows around the city, performing a mix of sketch comedy and semi-improvised theatre. In 2012, the group disbanded when some of its members moved to Australia.

Wellington hosts shows in the annualNew Zealand International Comedy Festival.[164]

Visual arts

[edit]From 1936 to 1992, Wellington was home to theNational Art Gallery of New Zealand, when it was amalgamated intoMuseum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington is home to theNew Zealand Academy of Fine Artsand theArts Foundation of New Zealand. The city'sarts centre,Toi Pōneke, is a nexus of creative projects, collaborations, and multi-disciplinary production. Arts Programmes and Services Manager Eric Vaughn Holowacz and a small team based in the Abel Smith Street facility have produced ambitious initiatives such as Opening Notes,Drive by Art, andpublic artprojects. The city is home to the experimental arts publicationWhite Fungus. The Learning Connexion provides art classes. Other visual art galleries include the City Gallery.

- Te Ngākau Civic Squarewith theFernsartwork suspended above

Cuisine

[edit]Wellington is characterised by small dining establishments, and itscafé cultureis internationally recognised, being known for its large number of coffeehouses.[165][166]There are a few iconic cafés that started the obsession with coffee that Wellington has. One of these is the Deluxe Expresso Bar that opened in 1988.[167]Wellington Restaurants offer cuisines including from Europe, Asia and Polynesia; for dishes that have a distinctlyNew Zealand style, there are lamb, pork and cervena (venison), salmon, crayfish (lobster),Bluff oysters,pāua(abalone),mussels,scallops,pipisandtuatua(both New Zealand shellfish); kūmara (sweet potato);kiwifruitandtamarillo; andpavlova, the national dessert.[168]

Sport

[edit]

Wellington is the home to:

- Hurricanes–Super Rugbyteam based in Wellington

- Wellington Lions–ITM Cuprugby team

- Wellington Phoenix FC–football (soccer)club playing in the AustralasianA-League, the only fully professional football club in New Zealand

- Team Wellington– in the semi-professionalNew Zealand Football Championship

- Central Pulse–netballteam representing the Lower North Island in theANZ Championship, primarily based in Wellington

- Wellington FirebirdsandWellington Blaze– men's and women'scricketteams

- Wellington Saints– basketball team in theNational Basketball League

Government

[edit]Local

[edit]

Wellington city is administered by theterritorial authorityofWellington City Council. The present mayor of the Wellington City Council isTory Whanau, who waselected in 2022.

Wellington is also part of the widerWellington Region, administered by theGreater Wellington Region Council. The local authorities are responsible for a wide variety ofpublic services, which include management and maintenance of local roads, and land-use planning.[169]

Community boards

[edit]The Wellington City Council has created two localcommunity boardsunder the provisions of Part 4 of theLocal Government Act 2002[170]for certain parts of the city:

- The Tawa Community Board[3]representing the northern suburbs ofTawa,Grenada NorthandTakapū Valley;[1]and

- The Mākara/Ōhāriu Community Board[4]representing the rural suburbs ofOhariu,MākaraandMākara Beach.[1]

National

[edit]Wellington is covered by four general electorates:Mana,Ōhāriu,Rongotai, andWellington Central. It is also covered by two Māori electorates:Te Tai Hauāuru, andTe Tai Tonga. Each electorate returns one member to theNew Zealand House of Representatives. Two general electorates are held by theLabour Partyand two are held by theGreen Partyand the two Maori electorates are held byTe Pāti Māori.

In addition, there are a number of Wellington-based list MPs, who are elected via party lists.

Due to Wellington being the capital city of New Zealand, its residents are more likely to participate in politics compared to other cities in New Zealand.[19]

Education

[edit]Wellington offers a variety of college and university programs fortertiarystudents:

Victoria University of Wellingtonhas four campuses and works with a three-trimester system (beginning March, July, and November).[171]It enrolled 21,380 students in 2008; of these, 16,609 were full-time students. Of all students, 56% were female and 44% male. While the student body was primarily New Zealanders of European descent, 1,713 were Māori, 1,024 were Pacific students, 2,765 were international students. 5,751 degrees, diplomas and certificates were awarded. The university has 1,930 full-time employees.[172]

Massey Universityhas a Wellington campus known as the "creative campus" and offers courses in communication and business, engineering and technology, health and well-being, and creative arts. Its school of design was established in 1886 and has research centres for studying public health, sleep, Māori health, small & medium enterprises, disasters, and tertiary teaching excellence.[173]It combined with Victoria University to create theNew Zealand School of Music.[173]

TheUniversity of Otagohas a Wellington branch, with its Wellington School of Medicine and Health.

Whitireia New Zealandhas large campuses in Porirua, Wellington and Kapiti; theWellington Institute of Technologyand New Zealand's National Drama school,Toi Whakaari. The Wellington area has numerous primary and secondary schools.

Transport

[edit]

Wellington is served byState Highway 1in the west andState Highway 2in the east, meeting at theNgauranga Interchangenorth of the city centre, where SH 1 runs through the city to the airport. There are two other state highways in the wider region:State Highway 58which provides a direct connection between the Hutt Valley and Porirua, andState Highway 59which follows a coastal route between Linden and Mackays Crossing and was previously part of SH 1.[175][176]Road access into the capital is constrained by the mountainous terrain – between Wellington and the Kāpiti Coast, SH 1 passes through the steep and narrow Wainui Saddle, nearby SH 59 travels along the Centennial Highway, a narrow section of road between the Paekākāriki Escarpment and theTasman Sea, and between Wellington and Wairarapa SH 2 transverses theRimutaka Rangeson a similar narrow winding road. Wellington has two motorways: theJohnsonville–Porirua Motorway(largely part of SH 1, with the northernmost section part of SH 59) and theWellington Urban Motorway(entirely part of SH 1), which in combination with a small non-motorway section in the Ngauranga Gorge connect Porirua with Wellington city. A third motorway in the wider region, theTransmission Gully Motorwayforming part of the SH 1 route and officially opened on 30 March 2022, leaves the Johnsonville-Porirua Motorway at the boundary between Wellington and Porirua and provides the main route between Wellington and the wider North Island.[177]

Bus transport in Wellington is supplied by several different operators under the banner of Metlink. Buses serve almost every part of Wellington city, with most of them running along the "Golden Mile" fromWellington railway stationtoCourtenay Place. Until October 2017, there were ninetrolleybusroutes, all other buses running ondiesel. Thetrolleybus networkwas the last public system of its kind in theSouthern Hemisphere.[178]

Wellington lies at the southern end of theNorth Island Main Trunkrailway (NIMT) and theWairarapa Line, converging onWellington railway stationat the northern end of central Wellington. Two long-distance services leave from Wellington: theCapital Connection, for commuters fromPalmerston North, and theNorthern ExplorertoAuckland.

Fourelectrifiedsuburbanlines radiate from Wellington railway station to the outer suburbs to the north of Wellington – theJohnsonville Linethrough the hillside suburbs north of central Wellington; theKapiti Linealong the NIMT to Waikanae on the Kāpiti Coast via Porirua and Paraparaumu; theMelling Lineto Lower Hutt via Petone; and theHutt Valley Linealong the Wairarapa Line via Waterloo andTaitāto Upper Hutt. A diesel-hauled carriage service, theWairarapa Connection, connects several times daily to Masterton in the Wairarapa via the 8.8-kilometre-long (5.5 mi)Rimutaka Tunnel. Combined, these five services carry 11.64 million passengers per year.[179]CentrePort Wellingtonis the operator of the port of Wellington, and provides infrastructure for shipping and cargo, including the commercialwharves in Wellington Harbour. It also provides port services for theCook StraitferriestoPictonin theSouth Island, operated by state-ownedInterislanderand privateBluebridge. Local ferries connect Wellington city centre with Eastbourne and Seatoun.[180]

Wellington International Airportis 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) south-east of the city centre. It is serviced by flights from across New Zealand, Australia, Singapore (via Melbourne), and Fiji. Flights to other international destinations require a transfer at another airport, as aircraft range is limited by Wellington's short (2,081-metre or 6,827-foot)runway, which has become an issue in recent years regarding the Wellington region's economic performance.[181][182]

Infrastructure

[edit]Electric power

[edit]Wellington's first public electricity supply was established in 1904, alongside the introduction of electric trams, and was originally supplied at 105 volts 80 hertz. The conversion to the now-standard 230/400 volts 50 hertz began in 1925, the same year the city was connected to theMangahao hydroelectric scheme. Between 1924 and 1968, the city's supply was supplemented by a coal-fired power station at Evans Bay.[183]

Today, Wellington city is supplied from fourTranspowersubstations: Takapu Road, Kaiwharawhara, Wilton, and Central Park (Mount Cook).Wellington Electricityowns and operates the local distribution network.

The city is home to two large wind farms,West WindandMill Creek, which combined contribute up to 213 MW of electricity to the city and the national grid.

While Wellington experiences regular strong winds, and only 63% of Wellington Electricity's network is underground, the city has a very reliable power supply. In the year to March 2018, Wellington Electricity disclosed the average customer spent just 55 minutes without power due to unplanned outages.[184]

Natural gas

[edit]Wellington was one of the original nine towns and cities in New Zealand to be supplied with natural gas when theKapuni gas fieldentered production in 1970, and a 260-kilometre-long (160 mi) high-pressure pipeline from the field in Taranaki to the city was completed. The high-pressure transmission pipelines supplying Wellington are now owned and operated byFirst Gas, withPowercoowning and operating the medium- and low-pressure distribution pipelines within the urban area.[185]

The three waters

[edit]The "three waters" –drinking water,stormwater, andwastewaterservices for the Wellington metropolitan area are provided by five councils: Wellington City, Hutt, Upper Hutt and Porirua city councils, and theGreater WellingtonRegional Council. However, the water assets of these councils are managed by aninfrastructure asset managementcompany,Wellington Water.

Wellington's first piped water supply came from a spring in 1867.[186]Greater Wellington Regional Councilnow supplies Lower Hutt, Porirua, Upper Hutt and Wellington with up to 220 million litres a day.[187]The water comes fromWainuiomata River(since 1884),Hutt River(1914),Ōrongorongo River(1926) and theWaiwhetū Aquifer.[188]

There are four wastewater treatment stations serving the Wellington metropolitan area, located at:[189]

- Moa Point(serving Wellington city)

- Seaview (serving Lower Hutt and Upper Hutt)

- Karori (serving the suburb)

- Porirua (serving northern Wellington suburbs, Tawa and Porirua city)

The Wellington metropolitan area faces challenges with ageing infrastructure for the three waters, and there have been some significant failures, particularly in wastewater systems. The water supply is vulnerable to severe disruption during a major earthquake, although a wide range of projects are planned to improve the resilience of the water supply and allow a limited water supply post-earthquake.[190][191]

In May 2021, the Wellington City Council approved a 10-year plan that included expenditure of $2.7billion on water pipe maintenance and upgrades in Wellington city, and an additional $147 to $208 million for plant upgrades at the Moa Point wastewater treatment plant.[192]In November 2023, Wellington Water noted that on-going investment of $1 billion per annum was required to address water issues across the Greater Wellington region, but that this amount was beyond the funding capacity of councils.[193]

Media

[edit]Radio

[edit]Wellington isserved by 26 full-power radio stations: 17 on FM, four on AM, and five on both FM and AM.

Television

[edit]Television broadcasts began in Wellington on 1 July 1961 with the launch of channel WNTV1, becoming the third New Zealand city (after Auckland and Christchurch) to receive regular television broadcasts. WNTV1's main studios were in Waring Taylor Street in central Wellington and broadcast from a transmitter atop Mount Victoria. In 1967, the Mount Victoria transmitter was replaced with a more powerful transmitter atMount Kaukau.[194]In November 1969, WNTV1 was networked with its counterpart stations in Auckland, Christchurch and Dunedin to form NZBC TV.

In 1975, the NZBC was broken up, with Wellington and Dunedin studios taking over NZBC TV asTelevision Onewhile Auckland and Christchurch studios launchedTelevision Two. At the same time, the Wellington studios moved to the new purpose-builtAvalon Television Centrein Lower Hutt. In 1980, Televisions One and Two merged under a single company,Television New Zealand(TVNZ). The majority of television production moved to Auckland over the 1980s, culminating in the opening of TVNZ's new Auckland television centre in 1989.

Today, digital terrestrial television (Freeview) is available in the city, transmitting from Mount Kaukau plus three infill transmitters at Baxters Knob, Fitzherbert, and Haywards.[195]

Sister cities

[edit]Wellington hassister cityrelationships with the following cities:[196]

- Sydney, Australia (1983)

- Xiamen, China (1987)

- Sakai, Japan (1994)

- Beijing, China (2006)

- Canberra, Australia (2016)

Wellington is also a “friendly city” withRamallah, Palestine, and a 2023 council vote means both are expected to be sister cities in the future.[197][198]Wellington also has historical ties withChania, Greece;Harrogate, England; andÇanakkale, Turkey.[199]

Wellington metropolitan area

[edit]The widermetropolitan areafor Wellington encompasses areas administered by fourlocal authorities:Wellington Cityitself, on the peninsula between Cook Strait andWellington Harbour;Porirua CityonPorirua Harbourto the north, notable for its largeMāoriandPasifikacommunities; andLower Hutt CityandUpper Hutt City, largely suburban areas to the northeast, together known as theHutt Valley. Depending on the source, the Wellington metro area may includeWaikanae,ParaparaumuandPaekākārikion the Kāpiti Coast, and/orFeatherstonandGreytownin theWairarapa.

The urban areas of the four local authorities have a combined population of 434,500 residents as of June 2023.[9]

The four cities comprising the Wellington metropolitan area have a total population of 440,900 (June 2023),[9]with the urban area containing 98.5% of that population. The remaining areas are largely mountainous and sparsely farmed or parkland and are outside the urban area boundary. More than most cities, life is dominated by its central business district (CBD). Approximately 62,000 people work in the CBD, only 4,000 fewer than work in Auckland's CBD, despite that city having four times the population.

TheWaikanae-Paraparaumu-Paekākārikicombined urban area in the Kāpiti Coast district is sometimes included in the Wellington metro area[by whom?]due to its exurban nature and strong transport links with Wellington. If included as part of the Wellington metro, Waikanae-Paraparaumu-Paekākāriki would add 45,780 to the population (as of June 2023).[9]

FeatherstonandGreytownin the Wairarapa are rarely considered part of the Wellington metropolitan area, being physically separated from the rest of the metropolitan area by theRemutaka Range. However, both have significant proportions of their employed population working in Wellington city and the Hutt Valley (36.1% and 17.1% in 2006 respectively)[200]and are considered part of the Wellington functional urban area by Statistics New Zealand.[201]

The four urban areas combined had a usual resident population of 401,850 at the2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 26,307 people (7.0%) since the2013 census, and an increase of 42,726 people (11.9%) since the2006 census. There were 196,911 males and 204,936 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.961 males per female. Of the total population, 74,892 people (18.6%) were aged up to 15 years, 93,966 (23.4%) were 15 to 29, 185,052 (46.1%) were 30 to 64, and 47,952 (11.9%) were 65 or older.[202]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^The metro area combines the urban areas of Wellington, Porirua, Lower Hutt and Upper Hutt.

- ^(/ˈwɛlɪŋtən/;Māori:Te Whanganui-a-Tara[tɛˈɸaŋanʉiataɾa]orPōneke[ˈpɔːnɛkɛ])

- ^WhetherChristchurchor Wellington is New Zealand's second-largest city by population is debatable and depends on where the boundaries are drawn.[12]UsingStatistics New Zealandboundaries, Wellington is the third-largest urban area (384,800 vs 215,200),[9]territorial authority area (396,200 vs 216,200),[9], and functional urban area (470,814 vs 414,033).[13]

References

[edit]- ^abcd"Ward maps and boundaries".Wellington City Council. Retrieved8 August2022.

- ^Thorns, David; Schrader, Ben (11 March 2010)."City history and people – Towns to cities".Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved15 February2021.

- ^ab"Tawa Community Board".Wellington City Council. 8 December 2021. Retrieved6 February2022.

- ^ab"Mākara/Ōhāriu Community Board".Wellington City Council. 22 November 2021. Retrieved6 February2022.

- ^"2020 General Election electorates".Electoral Commission. Retrieved6 February2022.

- ^"Wellington Mayor chooses Laurie Foon as new deputy".Radio New Zealand. 21 October 2022.

- ^"Urban Rural 2020 (generalised) – GIS | | GIS Map Data Datafinder Geospatial Statistics | Stats NZ Geographic Data Service".datafinder.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved25 October2020.

- ^"StatsNZ Geographic Boundary Viewer".statsnz.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved8 March2022.

- ^abcdefghij"Subnational population estimates (RC, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)".Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved25 October2023.(regional councils);"Subnational population estimates (TA, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)".Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved25 October2023.(territorial authorities);"Subnational population estimates (urban rural), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)".Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved25 October2023.(urban areas)

- ^"Regional gross domestic product: Year ended March 2022".Statistics New Zealand. 24 March 2023. Retrieved4 April2023.

- ^"Wellington City postcode map"(PDF).NZ Post. Retrieved6 February2022.

- ^"Yeah, Nah: Is Wellington (or Christchurch) NZ's second city?". Stuff. 2 September 2022.

- ^"Functional urban areas – methodology and classification". Statistics New Zealand. 10 February 2021.

- ^Guinness World Records 2009. London, United Kingdom: Guinness World Records Ltd. 2008. p.277.ISBN978-1-904994-36-7.

- ^Karl Mathiesen (15 October 2015)."Where is the world's windiest city? Spoiler alert: it's not Chicago".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 12 July 2016. Retrieved13 August2016.

- ^abcdeWaitangi Tribunal (2003).Te Whanganui a Tara me ona takiwa : report on the Wellington District. Wellington, N.Z.: Legislation Direct.ISBN186956264X.OCLC53261192.

- ^Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu."Wellington's plan".teara.govt.nz. Retrieved15 November2021.

- ^Schrader, Ben (26 March 2015) [11 March 2010]."City planning – Early settlement planning".Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.Archivedfrom the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved23 September2023.

Wellington's plan was designed by New Zealand Company surveyor William Mein Smith in 1840. It comprised a series of interconnected grids which expanded along the town's valleys and up the lower slopes of hills.

- ^abcdeLevine, Stephen (20 June 2012)."Capital city – Wellington, capital city".Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.Archivedfrom the original on 5 February 2019. Retrieved23 May2019.

- ^Lim, Jason (29 November 2015)."Wellington Is Bigger On Tech And Innovation Than You Think".Forbes. Retrieved15 November2016.

- ^"Culture and creativity".www.wellingtonnz.com. Retrieved21 April2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^"Arts and culture".10yearplan.wellington.govt.nz. Retrieved21 April2022.

- ^Media, ShermansTravel."Kiwi Culture in Wellington: New Zealand's Creative Capital | ShermansTravel".www.shermanstravel.com. Retrieved21 April2022.

- ^Choudhury, Saheli Roy (9 June 2021)."These are the world's most livable cities in 2021".CNBC. Retrieved2 June2022.

- ^abc"2014 Quality of Living Worldwide City Rankings – Mercer Survey". www.mercer.com. 19 February 2014. Archived fromthe originalon 22 June 2013. Retrieved11 April2014.

- ^"Wellington named most liveable city for second year running".Stuff. 25 May 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved23 June2019.

- ^George, Damian (19 September 2016)."Huffington Post lauds Wellington's 'remarkable' creative resurgence".Stuff.Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved9 July2019.

- ^"Wellington: New Zealand's creative capital".TNZ Media.Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved9 July2019.

- ^"Wellington is a Smart City of the future".iStart leading the way to smarter technology investment.Archivedfrom the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved9 July2019.

- ^"The World According to GaWC 2020".GaWC – Research Network. Globalization and World Cities. Retrieved31 August2020.

- ^Wakefield, Edward Jerningham (1845).Adventure in New Zealand, Vol. 1, pub. John Murray.

- ^Love, Morris (3 March 2017)."Te Āti Awa of Wellington".Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved28 October2019.

- ^ab"Māori history".Wellington City Council. 30 December 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved9 July2019.

- ^"The Streets of my city, Wellington New ZealandArchived20 May 2017 at theWayback Machine" by F. L. Irvine-Smith (1948); digital copy on Wellington City Libraries website. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^Te One, Annie (2018).Mana Whenua, Mātaawaka, and Local Government: An Examination of Relationships Between Māori and Local Government in Wellington and the Hutt Valley(PDF)(PhD thesis). Australian National University. p. 192. Retrieved15 December2022.

- ^"Poneke".natlib.govt.nz. Retrieved8 October2022.

- ^"nekeneke – Te Aka Māori Dictionary".maoridictionary.co.nz. Retrieved28 April2024.

- ^"[untitled]".Maori Messenger: Te Karere Maori. p. 8 – via Papers Past.

Tenei pea kua ronga nga tangata maori i te kokotinga o te ringaringa o Tako i Poneke, kahore ra nei.

- ^"Poneke: Wellington places to visit".Department of Conservation. 20 February 2007. Archived fromthe originalon 20 February 2007. Retrieved19 June2015.

- ^Maclean, Chris (1 August 2015)."Wellington region – Early Māori history".Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved28 October2019.

- ^"Wellington – New Zealand Sign Language Online". Deaf Studies Research Unit,Victoria University of Wellington. Retrieved11 November2013.

- ^Maclean, Chris (1 August 2015)."Wellington region – Climate: Windy Wellington".Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved28 October2019.

- ^Waitangi Tribunal. (2003).Te Whanganui a Tara me ona takiwa : report on the Wellington District. Wellington, N.Z.: Legislation Direct. p. 17.ISBN186956264X.OCLC53261192.

- ^"Māori history".Wellington City Council. 30 December 2015.Archivedfrom the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved9 July2019.

- ^Waitangi Tribunal (2003).Te Whanganui a Tara me ona takiwa : report on the Wellington District. Wellington, N.Z.: Legislation Direct. p. 13.ISBN186956264X.OCLC53261192.

- ^Waitangi Tribunal, Te Whanganui a Tara me ona Takiwa, page 18,https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_68452530/Wai145.pdfArchived22 January 2019 at theWayback Machine

- ^Waitangi Tribunal, Te Whanganui a Tara me ona Takiwa, page 18

- ^"Deed of Settlement of Historical Claims signed between Taranaki Whānui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika and the Port Nicholson Block Settlement Trust and The Sovereign in Right of New Zealand"(PDF).New Zealand Government. 19 August 2008. p. 8. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 4 February 2018. Retrieved15 September2018.

The importance of the Harbour to Taranaki Whanui ki Te Upoko o Te Ika increased as trade was entered into early in the 19th century.

- ^Easther, John (1991).The Hutt River = Te-Awa-kai-rangi : a modern history, 1840–1990. Wellington [N.Z.]: Wellington Regional Council. pp. 24–29.ISBN0-909016-09-7.OCLC34915088.

- ^"History of New Zealand, 1769–1914 – A history of New Zealand 1769–1914".nzhistory.govt.nz.Ministry for Culture and Heritage.Archivedfrom the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved10 July2019.

- ^"Parliament moves to Wellington".nzhistory.govt.nz. Ministry for Culture and Heritage.Archivedfrom the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved25 April2019.

- ^Temple, Philip(1980).Wellington Yesterday. John McIndoe.ISBN0-86868-012-5.

- ^Maclean, Chris (9 July 2007)."Wellington region – Boom and bust: 1900–1940".Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.Archivedfrom the original on 20 July 2019. Retrieved23 May2019.

- ^Guinness World Records 2009. London, United Kingdom: Guinness World Records Ltd. 2008. p.277.ISBN978-1-904994-36-7.

- ^Karl Mathiesen."Where is the world's windiest city? Spoiler alert: it's not Chicago".The Guardian.Archivedfrom the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved19 January2016.

- ^Paxton, John, ed. (1999). "Wellington, New Zealand".The Penguin Encyclopedia of Places(3rd ed.) – viaCredo Reference.

- ^"New Zealand Disasters – Wahine Shipwreck". Christchurch City Libraries. 10 April 1968.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved28 July2009.

- ^"The 1848 Marlborough earthquake – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 30 March 2005.Archivedfrom the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved6 February2009.

- ^"The 1855 Wairarapa earthquake – Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand". Teara.govt.nz. 21 September 2007.Archivedfrom the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved6 February2009.

- ^"Government Buildings".New Zealand Heritage List/Rārangi Kōrero.Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved6 February2009.

- ^Dave Burgess (14 March 2011)."Shuddering in Wellington". Fairfax NZ.Archivedfrom the original on 23 March 2011. Retrieved28 October2012.

- ^Hank Schouten (2 June 2012)."How safe are the capital's office buildings?". Dominion Post.Archivedfrom the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved28 October2012.

- ^Kate Chapman (16 October 2012)."Councillors question quake costs". The Dominion Post.Archivedfrom the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved28 October2012.

- ^Dave Burgess & Hank Schouten (1 October 2011)."Quake shakes capital insurance market". The Dominion Post.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved28 October2012.