Neil Armstrong

|

Neil Armstrong

|

|

|---|---|

Armstrong in 1969

|

|

| Born |

Neil Alden Armstrong

August 5, 1930

Wapakoneta, Ohio, U.S.

|

| Died | August 25, 2012(aged 82)

Fairfield, Ohio, U.S.

|

| Education | Purdue University(BS) University of Southern California(MS) |

| Spouses |

Janet Shearon

(

m.1956;

div.1994)

Carol Knight

(

m.1994)

|

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | |

| Space career | |

| USAF/NASA astronaut | |

| Rank | Lieutenant,USN |

|

Time in space

|

8d 14h 12m |

| Selection | |

|

Total

EVAs

|

1 |

|

Total EVA time

|

2h 31m |

| Missions | |

|

Mission insignia

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Neil Alden Armstrong(August 5, 1930 – August 25, 2012) was an Americanastronautandaeronautical engineerwho in 1969 became thefirst person to walk on the Moon. He was also anaval aviator,test pilot, anduniversity professor.

Armstrong was born and raised inWapakoneta, Ohio. He enteredPurdue University, studyingaeronautical engineering, with theU.S. Navypaying his tuition under theHolloway Plan. He became amidshipmanin 1949 and anaval aviatorthe following year. He saw action in theKorean War, flying theGrumman F9F Pantherfrom theaircraft carrierUSSEssex. After the war, he completed his bachelor's degree at Purdue and became a test pilot at theNational Advisory Committee for Aeronautics(NACA)High-Speed Flight StationatEdwards Air Force Basein California. He was the project pilot onCentury Seriesfighters and flew theNorth American X-15seven times. He was also a participant in theU.S. Air Force'sMan in Space SoonestandX-20 Dyna-Soarhuman spaceflightprograms.

Armstrong joined theNASA Astronaut Corpsin thesecond group, which was selected in 1962. He made his firstspaceflightas command pilot ofGemini 8in March 1966, becomingNASA's first civilian astronaut to fly in space. During this mission with pilotDavid Scott, he performed the firstdockingof twospacecraft; the mission was aborted after Armstrong used some of his re-entry control fuel to stabilize a dangerous roll caused by a stuck thruster. During training for Armstrong's second and last spaceflight as commander ofApollo 11, he had to eject from theLunar Landing Research Vehiclemoments before a crash.

On July 20, 1969, Armstrong and Apollo 11Lunar Module(LM) pilotBuzz Aldrinbecame the first people toland on the Moon, and the next day they spent two and a half hours outside theLunar ModuleEaglespacecraft whileMichael Collinsremained in lunar orbit in theApollo Command ModuleColumbia. When Armstrong first stepped onto the lunar surface, he famously said: "That's one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."[1][2][3][4]It was broadcast live to an estimated 530 million viewers worldwide. Apollo 11 was a major U.S. victory in theSpace Race, by fulfilling a national goal proposed in 1961 by PresidentJohn F. Kennedy"of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth" before the end of the decade. Along with Collins and Aldrin, Armstrong was awarded thePresidential Medal of Freedomby PresidentRichard Nixonand received the 1969Collier Trophy. PresidentJimmy Carterpresented him with theCongressional Space Medal of Honorin 1978, he was inducted into theNational Aviation Hall of Famein 1979, and with his former crewmates received theCongressional Gold Medalin 2009.

After he resigned from NASA in 1971, Armstrong taught in the Department of Aerospace Engineering at theUniversity of Cincinnatiuntil 1979. He served on theApollo 13accident investigation and on theRogers Commission, which investigated theSpace ShuttleChallengerdisaster. In 2012, Armstrong died due tocomplicationsresulting fromcoronary bypass surgery, at the age of 82.

Early life and education

Armstrong was born nearWapakoneta, Ohio,[5]on August 5, 1930, the son of Viola Louise (née Engel) and Stephen Koenig Armstrong. He was of German, English, Scots-Irish, and Scottish descent.[6][7]He is a descendant ofClan Armstrong.[8][9]He had a younger sister, June, and a younger brother, Dean. His father was anauditorfor theOhio state government,[10]and the family moved around the state repeatedly, living in 16 towns over the next 14 years.[11]Armstrong's love for flying grew during this time, having started at the age of two when his father took him to theCleveland Air Races. When he was five or six, he experienced his first airplane flight inWarren, Ohio, when he and his father took a ride in aFord Trimotor(also known as the "Tin Goose").[12][13]

The family's last move was in 1944 and took them back to Wapakoneta, where Armstrong attendedBlume High Schooland took flying lessons at the Wapakoneta airfield.[5]He earned a student flight certificate on his 16th birthday, thensoloedin August, all before he had a driver's license.[14]He was an activeBoy Scoutand earned the rank ofEagle Scout.[15]As an adult, he was recognized by the Scouts with theirDistinguished Eagle Scout AwardandSilver Buffalo Award.[16][17]While flying toward the Moon on July 18, 1969, he sent his regards to attendees at theNational Scout jamboreein Idaho.[18]Among the few personal items that he carried with him to the Moon and back was a World Scout Badge.[19]

At age 17, in 1947, Armstrong began studyingaeronautical engineeringatPurdue UniversityinWest Lafayette, Indiana; he was the second person in his family to attend college. Armstrong was also accepted to theMassachusetts Institute of Technology(MIT),[20]but he resolved to go to Purdue after watching afootballgame between thePurdue Boilermakersand theOhio State Buckeyesat theOhio Stadiumin 1945 in which quarterbackBob DeMossled the Boilermakers to a sound victory over the highly regarded Buckeyes.[21]An uncle who attended MIT had also advised him that he could receive a good education without going all the way toCambridge, Massachusetts. His college tuition was paid for under theHolloway Plan. Successful applicants committed to two years of study, followed by two years of flight training and one year of service as an aviator in theU.S. Navy, then completion of the final two years of theirbachelor's degree.[20]Armstrong did not take courses in naval science, nor did he join theNaval Reserve Officers Training Corps.[22]

Navy service

Armstrong's call-up from the Navy arrived on January 26, 1949, requiring him to report toNaval Air Station Pensacolain Florida for flight training with class 5-49. After passing the medical examinations, he became amidshipmanon February 24, 1949.[23]Flight training was conducted in aNorth American SNJ trainer, in which he soloed on September 9, 1949.[24]On March 2, 1950, he made his firstaircraft carrierlanding onUSSCabot, an achievement he considered comparable to his first solo flight.[24]He was then sent toNaval Air Station Corpus Christiin Texas for training on theGrumman F8F Bearcat, culminating in a carrier landing onUSSWright. On August 16, 1950, Armstrong was informed by letter that he was a fully qualifiednaval aviator. His mother and sister attended his graduation ceremony on August 23, 1950.[25]

Armstrong was assigned to Fleet Aircraft Service Squadron7 (FASRON 7) atNAS San Diego(now known as NAS North Island). On November 27, 1950, he was assigned toVF-51, an all-jet squadron, becoming its youngest officer, and made his first flight in a jet, aGrumman F9F Panther, on January 5, 1951. He was promoted toensignon June 5, 1951, and made his first jet carrier landing onUSSEssextwo days later. On June 28, 1951,Essexhad set sail for Korea, with VF-51 aboard to act asground-attack aircraft. VF-51 flew ahead toNaval Air Station Barbers Pointin Hawaii, where it conducted fighter-bomber training before rejoining the ship at the end of July.[26]

On August 29, 1951, Armstrong saw action in theKorean Waras an escort for a photoreconnaissanceplane overSongjin.[27]Five days later, on September 3, he flew armed reconnaissance over the primary transportation and storage facilities south of the village of Majon-ni, west ofWonsan. According to Armstrong, he was making a low bombing run at 350 mph (560 km/h) when 6 feet (1.8 m) of his wing was torn off after it collided with a cable that was strung across the hills as a booby trap. He was flying 500 feet (150 m) above the ground when he hit it. While there was heavy anti-aircraft fire in the area, none hit Armstrong's aircraft.[28]An initial report to the commanding officer ofEssexsaid that Armstrong's F9F Panther was hit byanti-aircraft fire. The report indicated he was trying to regain control and collided with a pole, which sliced off 2 feet (0.61 m) of the Panther's right wing. Further perversions of the story by different authors added that he was only 20 feet (6.1 m) from the ground and that 3 feet (0.91 m) of his wing was sheared off.[29]

Armstrong flew the plane back to friendly territory, but due to the loss of theaileron,ejectionwas his only safe option. He intended to eject over water and await rescue by Navy helicopters, but his parachute was blown back over land. A jeep driven by a roommate from flight school picked him up; it is unknown what happened to the wreckage of his aircraft, F9F-2 BuNo125122.[30]

In all, Armstrong flew 78missions over Korea for a total of 121hours in the air, a third of them in January 1952, with the final mission on March 5, 1952. Of 492 U.S. Navy personnel killed in the Korean War, 27 of them were fromEssexon this war cruise. Armstrong received theAir Medalfor 20 combat missions, twogold starsfor the next 40, theKorean Service Medaland Engagement Star, theNational Defense Service Medal, and theUnited Nations Korea Medal.[31]

Armstrong's regular commission was terminated on February 25, 1952, and he became an ensign in theUnited States Navy Reserve. On completion of his combat tour withEssex, he was assigned to a transport squadron, VR-32, in May 1952. He was released from active duty on August 23, 1952, but remained in the reserve, and was promoted tolieutenant (junior grade)on May 9, 1953.[32]As a reservist, he continued to fly, with VF-724 atNaval Air Station Glenviewin Illinois, and then, after moving to California, with VF-773 atNaval Air Station Los Alamitos.[33]He remained in the reserve for eight years, before resigning his commission on October 21, 1960.[32]

College years

After his service with the Navy, Armstrong returned to Purdue. His previously earned good but not outstandinggradesnow improved, lifting his final Grade Point Average (GPA) to a respectable but not outstanding 4.8 out of 6.0. He pledged thePhi Delta Thetafraternity, and lived in its fraternity house. He wrote and co-directed two musicals as part of the all-student revue. The first was a version ofSnow White and the Seven Dwarfs, co-directed with his girlfriend Joanne Alford from theAlpha Chi Omegasorority, with songs from the1937 Walt Disney film, including "Someday My Prince Will Come"; the second was titledThe Land of Egelloc("college" spelled backward), with music fromGilbert and Sullivanbut new lyrics.

Armstrong was chairman of the Purdue Aero Flying Club, and flew the club's aircraft, anAeroncaand a couple ofPipers, which were kept at nearby Aretz Airport inLafayette, Indiana. Flying the Aeronca to Wapakoneta in 1954, he damaged it in a rough landing in a farmer's field, and it had to be hauled back to Lafayette on a trailer.[34]He was abaritoneplayer in thePurdue All-American Marching Band.[35]Ten years later he was made an honorary member ofKappa Kappa Psinational band honorary fraternity.[36]Armstrong graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree inAeronautical Engineeringin January 1955.[33]In 1970, he completed his Master of Science degree inAerospace Engineeringat theUniversity of Southern California(USC).[37]He would eventually be awarded honorary doctorates by several universities.[38]

Armstrong met Janet Elizabeth Shearon, who was majoring inhome economics, at a party hosted by Alpha Chi Omega.[39]According to the couple, there was no real courtship, and neither could remember the exact circumstances of their engagement. They were married on January 28, 1956, at the Congregational Church inWilmette, Illinois. When he moved toEdwards Air Force Base, he lived in the bachelor quarters of the base, while Janet lived in theWestwooddistrict of Los Angeles. After one semester, they moved into a house inAntelope Valley, near Edwards AFB. Janet did not finish her degree, a fact she regretted later in life. The couple had three children.[40]In June 1961, their daughter Karen was diagnosed withdiffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, amalignanttumorof the middle part of herbrain stem.[41]X-ray treatment slowed its growth, but her health deteriorated to the point where she could no longer walk or talk. She died ofpneumonia, related to her weakened health, on January 28, 1962, aged two.[42]

Test pilot

Following his graduation from Purdue, Armstrong became an experimental research test pilot. He applied at theNational Advisory Committee for Aeronautics(NACA)High-Speed Flight Stationat Edwards Air Force Base.[43]NACA had no open positions, and forwarded his application to theLewis Flight Propulsion LaboratoryinCleveland, where Armstrong made his first test flight on March 1, 1955.[43]Armstrong's stint at Cleveland lasted only a couple of months before a position at the High-Speed Flight Station became available, and he reported for work there on July 11, 1955.[44]

On his first day, Armstrong was tasked with pilotingchase planesduring releases of experimental aircraft from modified bombers. He also flew the modified bombers, and on one of these missions had his first flight incident at Edwards. On March 22, 1956, he was in aBoeing B-29 Superfortress,[45]which was to air-drop aDouglas D-558-2 Skyrocket. He sat in the right-hand co-pilot seat while pilot in command, Stan Butchart sat in the left-hand pilot seat flying the B-29.[46]

As they climbed to 30,000 feet (9 km), thenumber-four enginestopped and thepropellerbegan windmilling (rotating freely) in the airstream. Hitting the switch that would stop the propeller's spinning, Butchart watched it slow, then resume spinning even faster than the others; if it spun too fast, it would break apart. Their aircraft needed to hold an airspeed of 210 mph (338 km/h) to launch its Skyrocket payload, and the B-29 could not land with the Skyrocket attached to its belly. Armstrong and Butchart brought the aircraft into a nose-downattitudeto increase speed, then launched the Skyrocket. At the instant of launch, the number-four engine propeller disintegrated. Pieces of it damaged the number-three engine and hit the number-two engine. Butchart and Armstrong were forced to shut down the damaged number-three engine, along with the number-one engine, due to thetorqueit created. They made a slow, circling descent from 30,000 ft (9 km) using only the number-two engine, and landed safely.[47]

Armstrong served as project pilot onCentury Seriesfighters, including theNorth American F-100 Super SabreA and C variants, theMcDonnell F-101 Voodoo, theLockheed F-104 Starfighter, theRepublic F-105 Thunderchiefand theConvair F-106 Delta Dart. He also flew theDouglas DC-3,Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star,North American F-86 Sabre,McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II,Douglas F5D-1 Skylancer, Boeing B-29 Superfortress,Boeing B-47 StratojetandBoeing KC-135 Stratotanker, and was one of eight elite pilots involved in theParasevparaglider research vehicle program.[48]Over his career, he flew more than 200 different models of aircraft.[37]His first flight in arocket-powered aircraftwas on August 15, 1957, in theBell X-1B, to an altitude of 11.4 miles (18.3 km). On landing, the poorly designednose landing gearfailed, as had happened on about a dozen previous flights of the Bell X-1B. He flew theNorth American X-15seven times,[49]including the first flight with the Q-ball system, the first flight of the number3 X-15 airframe, and the first flight of the MH-96 adaptive flight control system.[50][51]He became an employee of theNational Aeronautics and Space Administration(NASA) when it was established on October 1, 1958, absorbing NACA.[52]

Armstrong was involved in several incidents that went down in Edwards folklore or were chronicled in the memoirs of colleagues. During his sixth X-15 flight on April 20, 1962, Armstrong was testing the MH-96 control system when he flew to a height of over 207,000 feet (63 km) (the highest he flew beforeGemini 8). He held up the aircraft nose during its descent to demonstrate the MH-96's g-limiting performance, and the X-15 ballooned back up to around 140,000 feet (43 km). He flew past the landing field atMach3 at over 100,000 feet (30 km) in altitude, and ended up 40 miles (64 km) south of Edwards. After sufficient descent, he turned back toward the landing area, and landed. It was the longest X-15 flight in both flight time and length of the ground track.[53][54]

Fellow astronautMichael Collinswrote that of the X-15 pilots Armstrong "had been considered one of the weaker stick-and-rudder men, but the very best when it came to understanding the machine's design and how it operated".[55]Many of the test pilots at Edwards praised Armstrong's engineering ability.Milt Thompsonsaid he was "the most technically capable of the early X-15 pilots".Bill Danasaid Armstrong "had a mind that absorbed things like a sponge". Those who flew for the Air Force tended to have a different opinion, especially people likeChuck YeagerandPete Knight, who did not have engineering degrees. Knight said that pilot-engineers flew in a way that was "more mechanical than it is flying", and gave this as the reason why some pilot-engineers got into trouble: Their flying skills did not come naturally.[56]Armstrong made sevenflights in the X-15between November 30, 1960, and July 26, 1962.[57]He reached a top speed of Mach 5.74 (3,989 mph, 6,420 km/h) in the X-15-1, and left the Flight Research Center with a total of 2,400 flying hours.[58]

On April 24, 1962, Armstrong flew for the only time with Yeager. Their job, flying a T-33, was to evaluate Smith Ranch Dry Lake in Nevada for use as an emergency landing site for the X-15. In his autobiography, Yeager wrote that he knew the lake bed was unsuitable for landings after recent rains, but Armstrong insisted on flying out anyway. As they attempted atouch-and-go, the wheels became stuck and they had to wait for rescue. As Armstrong told the story, Yeager never tried to talk him out of it and they made a first successful landing on the east side of the lake. Then Yeager told him to try again, this time a bit slower. On the second landing, they became stuck, provoking Yeager to fits of laughter.[59]

On May 21, 1962, Armstrong was involved in the "Nellis Affair". He was sent in an F-104 to inspectDelamar Dry Lakein southern Nevada, again for emergency landings. He misjudged his altitude and did not realize that the landing gear had not fully extended. As he touched down, the landing gear began to retract; Armstrong applied full power to abort the landing, but the ventral fin and landing gear door struck the ground, damaging the radio and releasinghydraulic fluid. Without radio communication, Armstrong flew south toNellis Air Force Base, past the control tower, and waggled his wings, the signal for a no-radio approach. The loss of hydraulic fluid caused thetailhookto release, and upon landing, he caught the arresting wire attached to an anchor chain, and dragged the chain along the runway.[60]

It took thirty minutes to clear the runway and rig another arresting cable. Armstrong telephoned Edwards and asked for someone to collect him. Milt Thompson was sent in an F-104B, the only two-seater available, but a plane Thompson had never flown. With great difficulty, Thompson made it to Nellis, where a strong crosswind caused a hard landing and the left main tire suffered a blowout. The runway was again closed to clear it, and Bill Dana was sent to Nellis in a T-33, but he almost landed long. The Nellis base operations office then decided that to avoid any further problems, it would be best to find the three NASA pilots ground transport back to Edwards.[60]

Astronaut career

In June 1958, Armstrong was selected for the U.S. Air Force'sMan in Space Soonestprogram, but theAdvanced Research Projects Agency(ARPA) canceled its funding on August 1, 1958, and on November 5, 1958, it was superseded byProject Mercury, a civilian project run by NASA. As a NASA civilian test pilot, Armstrong was ineligible to become one of its astronauts at this time, as selection was restricted to military test pilots.[61][62]In November 1960, he was chosen as part of the pilot consultant group for theX-20 Dyna-Soar, a military space plane under development by Boeing for the U.S. Air Force, and on March 15, 1962, he was selected by the U.S. Air Force as one of seven pilot-engineers who would fly the X-20 when it got off the design board.[63][64]

In April 1962, NASA sought applications for the second group of NASA astronauts forProject Gemini, a proposed two-man spacecraft. This time, selection was open to qualified civilian test pilots.[65]Armstrong visited theSeattle World's Fairin May 1962 and attended a conference there on space exploration that was co-sponsored by NASA. After he returned fromSeattleon June 4, he applied to become an astronaut. His application arrived about a week past the June 1, 1962, deadline, but Dick Day, a flight simulator expert with whom Armstrong had worked closely at Edwards, saw the late arrival of the application and slipped it into the pile before anyone noticed.[66]AtBrooks Air Force Baseat the end of June, Armstrong underwent a medical exam that many of the applicants described as painful and at times seemingly pointless.[67]

NASA's Director of Flight Crew Operations,Deke Slayton, called Armstrong on September 13, 1962, and asked whether he would be interested in joining theNASA Astronaut Corpsas part of what the press dubbed "theNew Nine"; without hesitation, Armstrong said yes. The selections were kept secret until three days later, although newspaper reports had circulated since earlier that year that he would be selected as the "first civilian astronaut".[68]Armstrong was one of two civilian pilots selected for this group;[69]the other wasElliot See, another former naval aviator.[70]NASA selected the second group that, compared with theMercury Sevenastronauts, were younger,[67]and had more impressive academic credentials.[71]Collins wrote that Armstrong was by far the most experienced test pilot in the Astronaut Corps.[55]

Gemini program

Gemini 5

On February 8, 1965, Armstrong and Elliot See were picked as the backup crew forGemini 5, with Armstrong as commander, supporting the prime crew ofGordon CooperandPete Conrad.[72]The mission's purpose was to practicespace rendezvousand to develop procedures and equipment for a seven-day flight, all of which would be required for a mission to the Moon. With two other flights (Gemini 3andGemini 4) in preparation, six crews were competing for simulator time, so Gemini5 was postponed. It finally lifted off on August 21.[73]Armstrong and See watched the launch atCape Kennedy, then flew to theManned Spacecraft Center(MSC) in Houston.[74]The mission was generally successful, despite a problem with thefuel cellsthat prevented a rendezvous. Cooper and Conrad practiced a "phantom rendezvous", carrying out the maneuver without a target.[75]

Gemini 8

The crews for Gemini8 were assigned on September 20, 1965. Under the normal rotation system, the backup crew for one mission became the prime crew for the third mission after, but Slayton designatedDavid Scottas the pilot of Gemini8.[76][77]Scott was the first member of thethird group of astronauts, who was selected on October 18, 1963, to receive a prime crew assignment.[78]See was designated to commandGemini 9. Henceforth, each Gemini mission was commanded by a member of Armstrong's group, with a member of Scott's group as the pilot. Conrad would be Armstrong's backup this time, andRichard F. Gordon Jr.his pilot.[76][77]Armstrong became the first American civilian in space. (Valentina Tereshkovaof theSoviet Unionhad become the first civilian—and first woman—nearly three years earlier aboardVostok 6when it launched on June 16, 1963.[79]) Armstrong would also be the last of his group to fly in space, as See died in aT-38 crashon February 28, 1966, that also took the life of crewmateCharles Bassett. They were replaced by the backup crew ofTom StaffordandGene Cernan, whileJim Lovelland Buzz Aldrin moved up from the backup crew ofGemini 10to become the backup for Gemini 9,[80]and would eventually flyGemini 12.[81]

Gemini 8 launched on March 16, 1966. It was the most complex mission yet, with a rendezvous and docking with anuncrewedAgena target vehicle, and the planned second Americanspacewalk(EVA) by Scott. The mission was planned to last 75hours and 55orbits. After the Agena lifted off at 10:00:00EST,[82]theTitan IIrocket carrying Armstrong and Scott ignited at 11:41:02 EST, putting them into an orbit from which they chased the Agena.[83]They achieved the first-ever docking between two spacecraft.[84]Contact with the crew was intermittent due to the lack of tracking stations covering their entire orbits. While out of contact with the ground, the docked spacecraft began to roll, and Armstrong attempted to correct this with the Gemini'sOrbit Attitude and Maneuvering System(OAMS). Following the earlier advice of Mission Control, they undocked, but the roll increased dramatically until they were turning about once per second, indicating a problem with Gemini'sattitude control. Armstrong engaged the Reentry Control System (RCS) and turned off the OAMS. Mission rules dictated that once this system was turned on, the spacecraft had to reenter at the next possible opportunity. It was later thought that damaged wiring caused one of the thrusters to stick in the on position.[85]

A few people in the Astronaut Office, includingWalter Cunningham, felt that Armstrong and Scott "had botched their first mission".[86]There was speculation that Armstrong could have salvaged the mission if he had turned on only one of the two RCS rings, saving the other for mission objectives. These criticisms were unfounded; no malfunction procedures had been written, and it was possible to turn on only both RCS rings, not one or the other.[87]Gene Kranzwrote, "The crew reacted as they were trained, and they reacted wrong because we trained them wrong." The mission planners and controllers had failed to realize that when two spacecraft were docked, they must be considered one spacecraft. Kranz considered this the mission's most important lesson.[88]Armstrong was depressed that the mission was cut short,[89]canceling most mission objectives and robbing Scott of his EVA. The Agena was later reused as a docking target by Gemini 10.[90]Armstrong and Scott received theNASA Exceptional Service Medal,[91][92]and the Air Force awarded Scott theDistinguished Flying Crossas well.[93]Scott was promoted tolieutenant colonel, and Armstrong received a $678 raise in pay to $21,653 a year (equivalent to $203,338 in 2023), making him NASA's highest-paid astronaut.[89]

Gemini 11

In Armstrong's final assignment in the Gemini program, he was the back-up Command Pilot forGemini 11. Having trained for two flights, Armstrong was quite knowledgeable about the systems and took on a teaching role for the rookie backup pilot,William Anders.[94]The launch was on September 12, 1966,[95]with Conrad and Gordon on board, who successfully completed the mission objectives, while Armstrong served as acapsule communicator(CAPCOM).[96]

Following the flight, PresidentLyndon B. Johnsonasked Armstrong and his wife to take part in a 24-day goodwill tour of South America.[97]Also on the tour, which took in 11countries and 14major cities, were Dick Gordon,George Low, their wives, and other government officials. In Paraguay, Armstrong greeted dignitaries in their local language,Guarani; in Brazil he talked about the exploits of the Brazilian-born aviation pioneerAlberto Santos-Dumont.[98]

Apollo program

On January 27, 1967—the day of theApollo 1 fire—Armstrong was in Washington, D.C., with Cooper, Gordon, Lovell andScott Carpenterfor the signing of the United NationsOuter Space Treaty. The astronauts chatted with the assembled dignitaries until 18:45, when Carpenter went to the airport, and the others returned to the Georgetown Inn, where they each found messages to phone the MSC. During these calls, they learned of the deaths ofGus Grissom,Ed WhiteandRoger Chaffeein the fire. Armstrong and the group spent the rest of the night drinking scotch and discussing what had happened.[99]

On April 5, 1967, the same day the Apollo1 investigation released its final report, Armstrong and 17 other astronauts gathered for a meeting with Slayton. The first thing Slayton said was, "The guys who are going to fly the first lunar missions are the guys in this room."[100]According to Cernan, only Armstrong showed no reaction to the statement. To Armstrong it came as no surprise—the room was full of veterans of Project Gemini, the only people who could fly the lunar missions. Slayton talked about the planned missions and named Armstrong to the backup crew forApollo 9, which at that stage was planned as amedium Earth orbittest of the combinedlunar moduleandcommand and service module.[101]

The crew was officially assigned on November 20, 1967.[102]For crewmates, Armstrong was assigned Lovell and Aldrin, from Gemini 12. After design and manufacturing delays of the lunar module (LM),Apollo 8and9 swapped prime and backup crews. Based on the normal crew rotation, Armstrong would command Apollo 11,[101]with one change: Collins on the Apollo8 crew began experiencing trouble with his legs. Doctors diagnosed the problem as a bony growth between his fifth and sixth vertebrae, requiring surgery.[103]Lovell took his place on the Apollo8 crew, and, when Collins recovered, he joined Armstrong's crew.[104]

To give the astronauts practice piloting the LM on its descent, NASA commissionedBell Aircraftto build twoLunar Landing Research Vehicles(LLRV), later augmented with three Lunar Landing Training Vehicles (LLTV). Nicknamed the "Flying Bedsteads", they simulated the Moon's one-sixth gravity using aturbofanengine to support five-sixths of the craft's weight. On May 6, 1968, 100 feet (30 m) above the ground, Armstrong's controls started to degrade and the LLRV beganrolling.[105]He ejected safely before the vehicle struck the ground and burst into flames. Later analysis suggested that if he had ejected half a second later, his parachute would not have opened in time. His only injury was from biting his tongue. The LLRV was completely destroyed.[106]Even though he was nearly killed, Armstrong maintained that without the LLRV and LLTV, the lunar landings would not have been successful, as they gave commanders essential experience in piloting the lunar landing craft.[107]

In addition to the LLRV training, NASA began lunar landing simulator training after Apollo 10 was completed. Aldrin and Armstrong trained for a variety of scenarios that could develop during a real lunar landing.[108]They also received briefings from geologists at NASA.[109]

Apollo 11

After Armstrong served as backup commander for Apollo8, Slayton offered him the post of commander of Apollo 11 on December 23, 1968, as Apollo8 orbited the Moon.[110]According to Armstrong's 2005 biography, Slayton told him that although the planned crew was Commander Armstrong, Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin, and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins, he was offering Armstrong the chance to replace Aldrin with Jim Lovell. After thinking it over for a day, Armstrong told Slayton he would stick with Aldrin, as he had no difficulty working with him and thought Lovell deserved his own command. Replacing Aldrin with Lovell would have made Lovell the lunar module pilot, unofficially the lowest ranked member, and Armstrong could not justify placing Lovell, the commander of Gemini 12, in the number3 position of the crew.[111]The crew of Apollo 11 was assigned on January 9, 1969, as Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin, with Lovell, Anders, andFred Haiseas the backup crew.[112]

According toChris Kraft, a March 1969 meeting among Slayton, George Low,Bob Gilruth, and Kraft determined that Armstrong would be the first person on the Moon, in part because NASA management saw him as a person who did not have a large ego. A press conference on April 14, 1969, gave the design of the LM cabin as the reason for Armstrong's being first; the hatch opened inwards and to the right, making it difficult for the LM pilot, on the right-hand side, to exit first. At the time of their meeting, the four men did not know about the hatch consideration. The first knowledge of the meeting outside the small group came when Kraft wrote his book.[113][114]Methods of circumventing this difficulty existed, but it is not known if these were considered at the time. Slayton added, "Secondly, just on a pure protocol basis, I figured the commander ought to be the first guy out... I changed it as soon as I found they had the time line that showed that. Bob Gilruth approved my decision."[115]

Voyage to the Moon

ASaturn Vrocket launched Apollo 11 fromLaunch Complex 39Aat theKennedy Space Centeron July 16, 1969, at 13:32:00UTC(09:32:00 EDT local time).[116]Armstrong's wife Janet and two sons watched from a yacht moored on theBanana River.[117]During the launch, Armstrong's heart rate peaked at 110beats per minute.[118]He found the first stage the loudest, much noisier than the Gemini8 Titan II launch. The Apollo command module was relatively roomy compared with the Gemini spacecraft. None of the Apollo 11 crew sufferedspace sickness, as some members of previous crews had. Armstrong was especially glad about this, as he had been prone tomotion sicknessas a child and could experiencenauseaafter long periods ofaerobatics.[119]

Apollo 11's objective was to land safely on the Moon, rather than to touch down at a precise location. Three minutes into the lunar descent, Armstrong noted that craters were passing about two seconds too early, which meant theLunar ModuleEaglewould probably touch down several miles (kilometres) beyond the planned landing zone.[120]As theEagle's landingradaracquired the surface, several computer error alarms sounded. The first was a code1202alarm, and even with their extensive training, neither Armstrong nor Aldrin knew what this code meant. They promptly received word from CAPCOMCharles Dukein Houston that the alarms were not a concern; the 1202 and 1201 alarms were caused by executive overflows in thelunar module guidance computer. In 2007, Aldrin said the overflows were caused by his own counter-checklist choice of leaving the docking radar on during the landing process, causing the computer to process unnecessary radar data. When it did not have enough time to execute all tasks, the computer dropped the lower-priority ones, triggering the alarms. Aldrin said he decided to leave the radar on in case an abort was necessary when re-docking with the Apollo command module; he did not realize it would cause the processing overflows.[121]

When Armstrong noticed they were heading toward a landing area that seemed unsafe, he took manual control of the LM and attempted to find a safer area. This took longer than expected, and longer than most simulations had taken.[122]For this reason, Mission Control was concerned that the LM was running low on fuel.[123]On landing, Aldrin and Armstrong believed they had 40seconds of fuel left, including the 20seconds' worth which had to be saved in the event of an abort.[124]During training, Armstrong had, on several occasions, landed with fewer than 15seconds of fuel; he was also confident the LM could survive a fall of up to 50 feet (15 m). Post-mission analysis showed that at touchdown there were 45 to 50seconds of propellant burn time left.[125]

The landing on the surface of the Moon occurred several seconds after 20:17:40 UTC on July 20, 1969.[126]One of three 67-inch (170 cm) probes attached to three of the LM's four legs made contact with the surface, a panel light in the LM illuminated, and Aldrin called out, "Contact light." Armstrong shut the engine off and said, "Shutdown." As the LM settled onto the surface, Aldrin said, "Okay, engine stop"; then they both called out some post-landing checklist items. After a 10-second pause, Duke acknowledged the landing with, "We copy you down,Eagle." Armstrong confirmed the landing to Mission Control and the world with the words, "Houston,Tranquility Basehere. TheEaglehas landed." Aldrin and Armstrong celebrated with a brisk handshake and pat on the back. They then returned to the checklist of contingency tasks, should an emergency liftoff become necessary.[127][128][129]After Armstrong confirmed touch down, Duke re-acknowledged, adding a comment about the flight crew's relief: "Roger, Tranquility. We copy you on the ground. You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We're breathing again. Thanks a lot."[124]During the landing, Armstrong's heart rate ranged from 100 to 150beats per minute.[130]

First Moon walk

The flight plan called for a crew rest period before leaving the module, but Armstrong asked for this to be moved to earlier in the evening,Houston time. When he and Aldrin were ready to go outside,Eaglewas depressurized, the hatch was opened, and Armstrong made his way down the ladder.[131]At the bottom of the ladder, while standing on aLunar Modulelanding pad, Armstrong said, "I'm going to step off the LM now". He turned and set his left boot on the lunar surface at 02:56UTCJuly 21, 1969,[132]then said, "That's one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind."[133]The exact time of Armstrong's first step on the Moon is unclear.[134]

Armstrong prepared his famousepigramon his own.[135]In a post-flight press conference, he said that he chose the words "just prior to leaving the LM."[136]In a 1983 interview inEsquiremagazine, he explained toGeorge Plimpton: "I always knew there was a good chance of being able to return to Earth, but I thought the chances of a successful touch down on the moon surface were about even money—fifty–fifty... Most people don't realize how difficult the mission was. So it didn't seem to me there was much point in thinking of something to say if we'd have to abort landing."[135]In 2012, his brother Dean Armstrong said that Neil showed him a draft of the line months before the launch.[137]HistorianAndrew Chaikin, who interviewed Armstrong in 1988 for his bookA Man on the Moon, disputed that Armstrong claimed to have conceived the line during the mission.[138]

Recordings of Armstrong's transmission do not provide evidence for the indefinite article "a" before "man", though NASA and Armstrong insisted for years that static obscured it. Armstrong stated he would never make such a mistake, but after repeated listenings to recordings, he eventually conceded he must have dropped the "a".[133]He later said he "would hope that history would grant me leeway for dropping the syllable and understand that it was certainly intended, even if it was not said—although it might actually have been".[139]There have since been claims and counter-claims about whether acoustic analysis of the recording reveals the presence of the missing "a";[133][140]Peter Shann Ford, an Australian computer programmer, conducted a digital audio analysis and claims that Armstrong did say "a man", but the "a" was inaudible due to the limitations of communications technology of the time.[133][141][142]Ford andJames R. Hansen, Armstrong's authorized biographer, presented these findings to Armstrong and NASA representatives, who conducted their own analysis.[143]Armstrong found Ford's analysis "persuasive."[144][145]LinguistsDavid BeaverandMark Libermanwrote of their skepticism of Ford's claims on the blogLanguage Log.[146]A 2016 peer-reviewed study again concluded Armstrong had included the article.[147]NASA's transcript continues to show the "a" in parentheses.[148]

When Armstrong made his proclamation,Voice of Americawas rebroadcast live by theBBCand many other stations worldwide. An estimated 530million people viewed the event,[149]20 percent out of a world population of approximately 3.6billion.[150][151]

Q: Did you misspeak?

A: There isn't any way of knowing.

Q: Several sources say you did.

A: I mean, there isn't any way ofmyknowing. When I listen to the tape, I can't hear the 'a', but that doesn't mean it wasn't there, because that was the fastest VOX ever built. There was no mike-switch — it was avoice-operated key or VOX. In a helmet you find you lose a lot of syllables. Sometimes a short syllable like 'a' might not be transmitted. However, when I listen to it, I can't hear it. But the 'a' is implied, so I'm happy if they just put it in parentheses.

Omni, June 1982, p. 126

About 19minutes after Armstrong's first step, Aldrin joined him on the surface, becoming the second human to walk on the Moon. They began their tasks of investigating how easily a person could operate on the lunar surface. Armstrong unveiled a plaque commemorating the flight, and with Aldrin, planted theflag of the United States. Although Armstrong had wanted the flag to be draped on the flagpole,[152]it was decided to use a metal rod to hold it horizontally.[153]However, the rod did not fully extend, leaving the flag with a slightly wavy appearance, as if there were a breeze.[154]Shortly after the flag planting, PresidentRichard Nixonspoke to them by telephone from his office. He spoke for about a minute, after which Armstrong responded for about thirty seconds.[155]In the Apollo 11 photographic record, there are only five images of Armstrong partly shown or reflected. The mission was planned to the minute, with the majority of photographic tasks performed by Armstrong with the singleHasselbladcamera.[156]

After helping to set up theEarly Apollo Scientific Experiment Package, Armstrong went for a walk to what is now known as East Crater, 65 yards (59 m) east of the LM, the greatest distance traveled from the LM on the mission. His final task was to remind Aldrin to leave a small package of memorial items to SovietcosmonautsYuri GagarinandVladimir Komarov, and Apollo1 astronauts Grissom, White and Chaffee.[157]The Apollo 11 EVA lasted two and a half hours.[158]Each of the subsequent five landings was allotted a progressively longer EVA period; the crew ofApollo 17spent over 22hours exploring the lunar surface.[158]In a 2010 interview, Armstrong explained that NASA limited their Moon walk because they were unsure how thespace suitswould cope with the Moon's extremely high temperature.[159]

Return to Earth

After they re-entered the LM, the hatch was closed and sealed. While preparing for liftoff, Armstrong and Aldrin discovered that, in their bulky space suits, they had broken the ignition switch for the ascent engine; using part of a pen, they pushed in the circuit breaker to start the launch sequence.[160]TheEaglethen continued to its rendezvous in lunar orbit, where it docked withColumbia, the command and service module. The three astronauts returned to Earth and splashed down in the Pacific Ocean, to be picked up by theUSSHornet.[161]

After being released from an 18-day quarantine to ensure that they had not picked up any infections or diseases from the Moon, the crew was feted across the United States and around the world as part of a 38-day "Giant Leap" tour.[162]

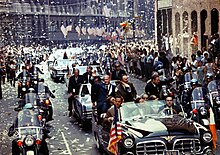

The tour began on August 13, when the three astronauts spoke and rode inticker-tape paradesin their honor in New York and Chicago, with an estimated six million attendees.[163][164]On the same evening an officialstate dinnerwas held in Los Angeles to celebrate the flight, attended by members of Congress, 44governors, theChief Justice of the United States, and ambassadors from 83nations. President Nixon and Vice President Agnew presented each astronaut with aPresidential Medal of Freedom.[163][165]

After the tour Armstrong took part inBob Hope's 1969USOshow, primarily to Vietnam.[166]In May 1970, Armstrong traveled to the Soviet Union to present a talk at the 13th annual conference of the InternationalCommittee on Space Research; after arriving inLeningradfrom Poland, he traveled to Moscow where he metPremierAlexei Kosygin. Armstrong was the first westerner to see the supersonicTupolev Tu-144and was given a tour of theYuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center, which he described as "a bit Victorian in nature".[167]At the end of the day, he was surprised to view a delayed video of the launch ofSoyuz 9as it had not occurred to Armstrong that the mission was taking place, even though Valentina Tereshkova had been his host and her husband,Andriyan Nikolayev, was on board.[168]

Life after Apollo

Teaching

Shortly after Apollo 11, Armstrong stated that he did not plan to fly in space again.[169]He was appointed Deputy Associate Administrator for Aeronautics for the Office of Advanced Research and Technology atARPA, served in the position for a year, then resigned from it and NASA in 1971.[170]He accepted a teaching position in the Department of Aerospace Engineering at theUniversity of Cincinnati,[171]having chosen Cincinnati over other universities, including hisalma materPurdue, because Cincinnati had a small aerospace department,[172]and said he hoped the faculty there would not be annoyed that he came straight into a professorship with only a USC master's degree.[173]He began his master's degree while stationed at Edwards years before, and completed it after Apollo 11 by presenting a report on various aspects of Apollo, instead of a thesis on the simulation of hypersonic flight.[174]

At Cincinnati, Armstrong was University Professor of Aerospace Engineering. He took a heavy teaching load, taught core classes, and created two graduate-level classes: aircraft design and experimental flight mechanics. He was considered a good teacher, and a tough grader. His research activities during this time did not involve his work at NASA, as he did not want to give the appearance of favoritism; he later regretted the decision. After teaching for eight years, Armstrong resigned in 1980. When the university changed from an independent municipal university to a state school, bureaucracy increased. He did not want to be a part of the faculty collective bargaining group, so he decided to teach half-time. According to Armstrong, he had the same amount of work but received half his salary. In 1979, less than 10% of his income came from his university salary. Employees at the university did not know why he left.[174]

NASA commissions

In 1970, after an explosion aboardApollo 13aborted its lunar landing, Armstrong was part ofEdgar Cortright's investigation of the mission. He produced a detailed chronology of the flight. He determined that a 28-volt thermostat switch in an oxygen tank, which was supposed to have been replaced with a 65-volt version, led to the explosion. Cortright's report recommended the entire tank be redesigned at a cost of $40million. Many NASA managers, including Armstrong, opposed the recommendation, since only the thermostat switch had caused the problem. They lost the argument, and the tanks were redesigned.[175]

In 1986, PresidentRonald Reaganasked Armstrong to join theRogers Commissioninvestigating theSpace ShuttleChallengerdisaster. Armstrong was made vice chairman of the commission and held private interviews with contacts he had developed over the years to help determine the cause of the disaster. He helped limit the committee's recommendations to nine, believing that if there were too many, NASA would not act on them.[176]

Armstrong was appointed to a fourteen-member commission by President Reagan to develop a plan for American civilian spaceflight in the 21st century. The commission was chaired by former NASA administrator Dr.Thomas O. Paine, with whom Armstrong had worked during the Apollo program. The group published a book titledPioneering the Space Frontier: The Report on the National Commission on Space, recommending a permanent lunar base by 2006, and sending people to Mars by 2015. The recommendations were largely ignored, overshadowed by theChallengerdisaster.[177]

Armstrong and his wife attended the memorial service for the victims of theSpace ShuttleColumbiadisasterin 2003, at the invitation of PresidentGeorge W. Bush.[178]

Business activities

After Armstrong retired from NASA in 1971, he acted as a spokesman for several businesses. The first company to successfully approach him wasChrysler, for whom he appeared in advertising starting in January 1979. Armstrong thought they had a strong engineering division, and they were in financial difficulty. He later acted as a spokesman for other American companies, including General Time Corporation and the Bankers Association of America.[179]He acted as a spokesman for only American companies.[180]

In addition to his duties as a spokesman, he also served on the board of directors of several companies. The first company board Armstrong joined wasGates Learjet, chairing their technical committee. He flew their new and experimental jets and even set a climb and altitude record for business jets. Armstrong became a member ofCincinnati Gas & Electric Company's board in 1973. They were interested in nuclear power and wanted to increase the company's technical competence. He served on the board ofTaft Broadcasting, also based in Cincinnati. Armstrong joined the board of solid rocket boosterThiokolin 1989, after previously serving on the Rogers Commission which found that theSpace ShuttleChallengerwas destroyed due to a defect in the Thiokol-manufactured solid rocket boosters. When Armstrong left the University of Cincinnati, he became the chairman of Cardwell International Ltd., a company that manufactured drilling rigs. He served on additional aerospace boards, firstUnited Airlinesin 1978, and laterEaton Corporationin 1980. He was asked to chair the board of directors for a subsidiary of Eaton, AIL Systems. He chaired the board through the company's 2000 merger withEDO Corporation, until his retirement in 2002.[181][182]

North Pole expedition

In 1985, professional expedition leader Mike Dunn organized a trip to take men he deemed the "greatest explorers" to the North Pole. The group included Armstrong,Edmund Hillary,Hillary's son Peter,Steve Fossett, andPatrick Morrow. They arrived at the Pole on April 6, 1985. Armstrong said he was curious to see what it looked like from the ground, as he had seen it only from the Moon.[183]He did not inform the media of the trip, preferring to keep it private.[184]

Public profile

Armstrong's family described him as a "reluctant American hero".[185][186][187]He kept a low profile later in his life, leading to the belief that he was a recluse.[188][189]Recalling Armstrong's humility,John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth, told CNN: "[Armstrong] didn't feel that he should be out huckstering himself. He was a humble person, and that's the way he remained after his lunar flight, as well as before."[190]Armstrong turned down most requests for interviews and public appearances. Michael Collins said in his bookCarrying the Firethat when Armstrong moved to a dairy farm to become a college professor, it was like he "retreated to his castle and pulled up the drawbridge". Armstrong found this amusing, and said, "...those of us that live out in the hinterlands think that people that live inside theBeltwayare the ones that have the problems."[191]

Andrew Chaikin says inA Man on the Moonthat Armstrong kept a low profile but was not a recluse, citing his participation in interviews, advertisements for Chrysler, and hosting a cable television series.[192]Between 1991 and 1993, he hostedFirst Flights with Neil Armstrong, anaviation historydocumentary series onA&E.[191]In 2010, Armstrong voiced the character of Dr. Jack Morrow inQuantum Quest: A Cassini Space Odyssey,[193]an animated educational sci-fi adventure film initiated by JPL/NASA through a grant from Jet Propulsion Lab.[194]

Armstrong guarded the use of his name, image, and famous quote. When it was launched in 1981,MTVwanted to use his quote in itsstation identification, with the American flag replaced with the MTV logo, but he refused the use of his voice and likeness.[195]He suedHallmark Cardsin 1994, when they used his name, and a recording of the "one small step" quote, in a Christmas ornament without his permission. The lawsuit was settled out of court for an undisclosed sum, which Armstrong donated to Purdue.[196][197]

For many years, he wrote letters congratulating new Eagle Scouts on their accomplishment, but decided to quit the practice in the 1990s because he felt the letters should be written by people who knew the scout. (In 2003, he received 950congratulation requests.) This contributed to the myth of his reclusiveness.[198]Armstrong used to autograph everything exceptfirst day covers. Around 1993, he found out his signatures were being sold online, and that most of them were forgeries, and stopped giving autographs.[189]

Personal life

Some former astronauts, including Glenn andApollo 17'sHarrison Schmitt, sought political careers after leaving NASA. Armstrong was approached by groups from both theDemocraticandRepublicanparties but declined the offers. He supportedstates' rightsand opposed the U.S. acting as the "world's policeman".[199]

When Armstrong applied at a localMethodistchurch to lead a Boy Scout troop in the late 1950s, he gave his religious affiliation as "deist".[200]His mother later said that his religious views caused her grief and distress in later life, as she was a Christian.[201]Upon his return from the Moon, Armstrong gave a speech in front of theU.S. Congressin which he thanked them for giving him the opportunity to see some of the "grandest views of the Creator".[202][203]In the early 1980s, he was the subject of a hoax claiming that he converted toIslamafter hearing thecall to prayerwhile walking on the Moon. Indonesian singer Suhaemi wrote a song called "Gema Suara Adzan di Bulan" ("The Resonant Sound of the Call to Prayer on the Moon") which described Armstrong's supposed conversion, and the song was widely discussed byJakartanews outlets in 1983.[204]Similar hoax stories were seen in Egypt and Malaysia. In March 1983, theU.S. State Departmentresponded by issuing a message to embassies and consulates in Muslim countries saying that Armstrong had not converted to Islam.[205]The hoax surfaced occasionally for the next three decades. Part of the confusion arose from the similarity between the names of the country of Lebanon, which has a majority Muslim population, and Armstrong's longtime residence inLebanon, Ohio.[205]

In 1972, Armstrong visited the Scottish town ofLangholm, the traditional seat of Clan Armstrong. He was made the firstfreemanof the burgh, and happily declared the town his home.[206]To entertain the crowd, theJustice of the Peaceread from an unrepealed archaic 400-year-old law that required him to hang any Armstrong found in the town.[207]

Armstrong flew light aircraft for pleasure. He enjoyedglidersand before the Moon flight had earned a gold badge with two diamonds from theInternational Gliding Commission. He continued to fly engineless aircraft well into his 70s.[208]

While working on his farm in November 1978, Armstrong jumped off the back of his grain truck and caught his wedding ring in its wheel, tearing the tip off his left ring finger. He collected the severed tip, packed it in ice, and had surgeons reattach it at a nearby hospital inLouisville, Kentucky.[209]In February 1991, he suffered a mild heart attack while skiing with friends atAspen, Colorado.[210]

Armstrong and his first wife, Janet, separated in 1990 and divorced in 1994 after 38 years of marriage.[211][212]He met his second wife, Carol Held Knight, at a golf tournament in 1992, when they were seated together at breakfast. She said little to Armstrong, but he called her two weeks later to ask what she was doing. She replied that she was cutting down a cherry tree, and he arrived at her house 35 minutes later to help. They were married in Ohio on June 12, 1994, and had a second ceremony atSan Ysidro Ranchin California. They lived inIndian Hill, Ohio.[213][214]Through his marriage to Carol, he was the father-in-law of futureNew York Metsgeneral managerBrodie Van Wagenen.

In May 2005, Armstrong became involved in a legal dispute with Mark Sizemore, his barber of 20years. After cutting Armstrong's hair, Sizemore sold some of it to a collector for $3,000 without Armstrong's knowledge or permission.[215]Armstrong threatened legal action against Sizemore unless he returned the hair or donated the proceeds to a charity of Armstrong's choosing. Sizemore, unable to retrieve the hair, donated the proceeds to charity.[216][217]

Illness and death

On August 7, 2012, two days after his 82nd birthday, Armstrong underwentbypass surgeryatMercy Faith–Fairfield HospitalinFairfield, Ohio, to relievecoronary artery disease.[218][219]Although he was reportedly recovering well,[220]he developed complications and died on August 25.[221][222]PresidentBarack Obamaissued a statement memorializing Armstrong as "among the greatest of American heroes—not just of his time, but of all time",[223][224]and added that Armstrong had carried the aspirations of the United States' citizens and had delivered "a moment of human achievement that will never be forgotten."[225]

Armstrong's family released a statement describing him as a "reluctant American hero [who had] served his nation proudly, as a navy fighter pilot, test pilot, and astronaut ... While we mourn the loss of a very good man, we also celebrate his remarkable life and hope that it serves as an example to young people around the world to work hard to make their dreams come true, to be willing to explore and push the limits, and to selflessly serve a cause greater than themselves. For those who may ask what they can do to honor Neil, we have a simple request. Honor his example of service, accomplishment and modesty, and the next time you walk outside on a clear night and see the moon smiling down at you, think of Neil Armstrong and give him a wink."[226]

Buzz Aldrin called Armstrong "a true American hero and the best pilot I ever knew", and said he was disappointed that they would not be able to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing together in 2019.[227][228]Michael Collins said, "He was the best, and I will miss him terribly."[229][230]NASA AdministratorCharles Boldensaid, "As long as there are history books, Neil Armstrong will be included in them, remembered for taking humankind's first small step on a world beyond our own".[231][232]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

A tribute was held for Armstrong on September 13, atWashington National Cathedral, whose Space Window depicts the Apollo 11 mission and holds a sliver of Moon rock amid its stained-glass panels.[233]In attendance were Armstrong's Apollo 11 crewmates, Collins and Aldrin; Gene Cernan, the Apollo 17 mission commander and last man to walk on the Moon; and former senator and astronaut John Glenn, the first American to orbit the Earth. In his eulogy, Charles Bolden praised Armstrong's "courage, grace, and humility". Cernan recalled Armstrong's low-fuel approach to the Moon: "When the gauge says empty, we all know there's a gallon or two left in the tank!"Diana Krallsang the song "Fly Me to the Moon". Collins led prayers. David Scott spoke, possibly for the first time, about an incident during their Gemini 8 mission: minutes before the hatch was to be sealed, a small chip of dried glue fell into the latch of his harness and prevented it from being buckled, threatening to abort the mission. Armstrong then called on Conrad to solve the problem, which he did, and the mission proceeded. "That happened because Neil Armstrong was a team player—he always worked on behalf of the team."[233]CongressmanBill Johnsonfrom Armstrong's home state of Ohio led calls for President Barack Obama to authorize astate funeralin Washington D.C. Throughout his lifetime, Armstrong shunned publicity and rarely gave interviews. Mindful that Armstrong would have objected to a state funeral, his family opted to have a private funeral inCincinnati.[234]On September 14, Armstrong's cremated remains were scattered in the Atlantic Ocean from theUSSPhilippine Sea.[235]Flags were flown athalf-staffon the day of Armstrong's funeral.[236]

In July 2019, after observations of the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing,The New York Timesreported on details of amedical malpracticesuit Armstrong's family had filed against Mercy Health–Fairfield Hospital, where he died. When Armstrong appeared to be recovering from his bypass surgery, nurses removed the wires connected to his temporarypacemaker. He began tobleed internallyand his blood pressure dropped. Doctors took him to the hospital'scatheterizationlaboratory, and only later began operating. Two of the three physicians who reviewed the medical files during the lawsuit called this a serious error, saying surgery should have begun immediately; experts theTimestalked to, while qualifying their judgement by noting that they were unable to review the specific records in the case, said that taking a patient directly to the operating room under those circumstances generally gave them the highest chance of survival.[218]

The family ultimately settled for $6 million in 2014. Letters included with the 93 pages of documents sent to theTimesby an unknown person[237]show that his sons intimated to the hospital, through their lawyers, that they might discuss what happened to their father publicly at the 45th anniversary observances in 2014. The hospital, fearing the bad publicity that would result from being accused of negligently causing the death of a revered figure such as Armstrong, agreed to pay as long as the family never spoke about the suit or the settlement.[218]Armstrong's wife, Carol, was not a party to the lawsuit. She reportedly felt that her husband would have been opposed to taking legal action.[238]

Legacy

When Pete Conrad ofApollo 12became the third man to walk on the Moon, on November 19, 1969, his first words referenced Armstrong. The shorter of the two, when Conrad stepped from the LM onto the surface he proclaimed "Whoopie! Man, that may have been a small one for Neil, but that's a long one for me."[239]

Armstrong received many honors and awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom (with distinction) from President Nixon,[163][240]theCullum Geographical Medalfrom theAmerican Geographical Society,[241]and theCollier Trophyfrom theNational Aeronautic Association(1969);[242]theNASA Distinguished Service Medal[243]and theDr. Robert H. Goddard Memorial Trophy(1970);[244]theSylvanus Thayer Awardby theUnited States Military Academy(1971);[245]theCongressional Space Medal of Honorfrom PresidentJimmy Carter(1978);[91]theWright Brothers Memorial Trophyfrom the National Aeronautic Association (2001);[246]and aCongressional Gold Medal(2011).[247]

Armstrong was elected as member into theNational Academy of Engineeringin 1978 for contributions to aerospace engineering, scientific knowledge, and exploration of the universe as an experimental test pilot and astronaut.[248]He was elected to theAmerican Philosophical Societyin 2001.[249]

Armstrong and his Apollo 11 crewmates were the 1999 recipients of theLangley Gold Medalfrom the Smithsonian Institution.[250]On April 18, 2006, he received NASA's Ambassador of Exploration Award.[251]TheSpace Foundationnamed Armstrong as a recipient of its 2013 General James E. Hill Lifetime Space Achievement Award.[252]Armstrong was also inducted into theAerospace Walk of Honor,[253][254]theInternational Space Hall of Fame,[255]National Aviation Hall of Fame, and theUnited States Astronaut Hall of Fame.[256][257]He was awarded hisNaval Astronaut badgein a ceremony on board the aircraft carrierUSSDwight D. Eisenhoweron March 10, 2010, in a ceremony attended by Lovell and Cernan.[258]

The lunar craterArmstrong, 31 miles (50 km) from the Apollo 11 landing site, andasteroid6469 Armstrongare named in his honor.[259]There are more than a dozen elementary, middle and high schools named for Armstrong in the United States,[260]and many places around the world have streets, buildings, schools, and other places named for him and/or Apollo.[261]TheArmstrong Air and Space Museum, in Armstrong's hometown of Wapakoneta,[262]and the Neil Armstrong Airport inNew Knoxville, Ohio, are named after him.[263]The mineralarmstrongiteis named after him,[264]and the mineralarmalcoliteis named, in part, after him.[265]

In October 2004 Purdue University named its new engineering buildingNeil Armstrong Hall of Engineering;[266]the building was dedicated on October 27, 2007, during a ceremony at which Armstrong was joined by fourteen other Purdue astronauts.[267]The NASA Dryden Flight Research Center was renamed the NASA Neil A. Armstrong Flight Research Center in 2014.[268]In September 2012, the U.S. Navy named the firstArmstrong-class vesselRVNeil Armstrong. Delivered to the Navy on September 23, 2015, it is a modern oceanographic research platform supporting a wide range of activities by academic groups.[269]In 2019, the College of Engineering at Purdue University celebrated the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong's walk on the Moon by launching the Neil Armstrong Distinguished Visiting Fellows Program, which brings highly accomplished scholars and practitioners to the college to catalyze collaborations with faculty and students.[270]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Armstrong's authorized biography,First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong, was published in 2005. For many years, he turned down biography offers from authors such asStephen AmbroseandJames A. Michenerbut agreed to work with James R. Hansen after reading one of Hansen's other biographies.[271]He recalled his initial concerns about the Apollo 11 mission, when he had believed there was only a 50% chance of landing on the Moon. "I was elated, ecstatic and extremely surprised that we were successful".[272]Afilm adaptation of the book, starringRyan Goslingand directed byDamien Chazelle, was released in October 2018.[273]

In July 2018, Armstrong's sons put his collection of memorabilia up for sale, including his Boy Scout cap, and various flags and medals flown on his space missions. A series of auctions held November 1–3, 2018, realized $5,276,320 (~$6.31 million in 2023). As of July 2019[update], the auction sales totaled $16.7million.[238]Two fragments of wood from the propeller and four pieces of fabric from the wing of the 1903Wright Flyerthat Armstrong took to the Moon fetched between $112,500 and $275,000 each.[274][275]Armstrong's wife, Carol, has not put any of his memorabilia up for sale.[238]

Armstrong donated his papers to Purdue. Along with posthumous donations by his widow Carol, the collection consists of over 450boxes of material. In May 2019, she donated two 25-by-24-inch (640 by 610 mm) pieces of fabric from theWright Flyer, along with his correspondence related to them.[276]

In a 2010Space Foundationsurvey, Armstrong was ranked as the number-one most popular space hero;[277]and in 2013,Flyingmagazine ranked him number one on its list of 51 Heroes of Aviation.[278]The press often asked Armstrong for his views on the future of spaceflight. In 2005, he said that ahuman mission to Marswould be easier than the lunar challenge of the 1960s. In 2010, he made a rare public criticism of the decision to cancel theAres Ilaunch vehicle and theConstellation Moon landing program.[279]In an open letter also signed by fellow Apollo veterans Lovell and Cernan, he said, "For The United States, the leading space faring nation for nearly half a century, to be without carriage to low Earth orbit and with no human exploration capability to go beyond Earth orbit for an indeterminate time into the future, destines our nation to become one of second or even third rate stature".[280]On November 18, 2010, aged 80, he said in a speech during theScience & Technology Summitinthe Hague, Netherlands, that he would offer his services as commander on a mission to Mars if he were asked.[281]

The planetarium atAltoona Area High SchoolinAltoona, Pennsylvaniais named after Armstrong and is home to aSpace Racemuseum.[282]A campsite in Camp Sandy Beach atYawgoog Scout ReservationinRockville, Rhode Island, is named in his honor, a nod to his Scouting career.

Armstrong was named theclass exemplarfor the Class of 2019 at the U.S. Air Force Academy.[283]

See also

- Apollo 11 in popular culture

- Cueva de los Tayos

- History of aviation

- List of spaceflight records

- Society of Experimental Test Pilots

- The Astronaut Monument

Notes

- ^"Armstrong's famous 'one small step' quote — explained".WHYY-FM. July 14, 2019. RetrievedJuly 13,2023.

- ^"July 20, 1969: One Giant Leap For Mankind".NASA. July 20, 2019. RetrievedAugust 13,2023.

- ^Armstrong, Neil (July 16, 1999)."[Press conference with Neil Armstrong]".NASA History Division. RetrievedAugust 13,2023.

- ^Stamm, Amy (July 17, 2019).""One Small Step for Man" or "a Man"?".National Air and Space Museum. RetrievedAugust 13,2023.

- ^abHansen 2005, pp. 49–50.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 13, 20.

- ^Coleman, Maureen (August 28, 2012)."A Giant Leap For An Ulsterman".The Belfast Telegraph. RetrievedNovember 14,2018.

- ^Harvey, Ian (April 15, 2019)."Neil Armstrong's Last Name Posed a Problem in his Ancestral Scottish Hometown".thevintagenews. RetrievedSeptember 4,2022.

- ^Scott, David (June 21, 2018)."Langholm, ancestral home of Neil Armstrong, tops town survey".Daily Express. RetrievedSeptember 4,2022.

- ^"Neil Armstrong grants rare interview to accountants organization". CBC News. May 24, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on January 7, 2018. RetrievedApril 8,2018.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 29.

- ^"Project Apollo: Astronaut Biographies". NASA.Archivedfrom the original on April 28, 2011. RetrievedMay 12,2011.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 45. "According to a volunteer group in Warren, Ohio that had worked through the 2000s to turn the Warren Airport into a historical exhibit, the date of Neil's inaugural flight was July 26, 1936. If that date is correct, Neil was still only five when he experienced his first airplane ride, his sixth birthday not coming for ten more days."

- ^Koestler-Grack 2010, p. 14.

- ^Hansen 2012, p. 38.

- ^Airgood, Glenn (February 16, 1973)."1st Man on the Moon Gets National Eagle Award".The Morning Call. Allentown, Pennsylvania. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^"Silver Buffalo Award Winners 1979–1970". Boy Scouts of America. RetrievedSeptember 2,2018.

- ^"Apollo 11 – Day 3, part 2: Entering Eagle – Transcript". NASA. April 11, 2010. RetrievedFebruary 14,2022.

I'd like to say hello to all my fellow Scouts and Scouters atFarragut State Parkin Idaho having aNational Jamboreethere this week; and Apollo 11 would like to send them best wishes".Capsule communicatorCharles Dukereplied: "Thank you, Apollo 11. I'm sure that, if they didn't hear that, they'll get the word through the news. Certainly appreciate that.

- ^"World Scouting salutes Neil Armstrong". World Organization of the Scout Movement. Archived fromthe originalon September 4, 2015. RetrievedJuly 27,2015.

- ^abHansen 2005, pp. 55–56.

- ^"The untold story of how Neil Armstrong chose Purdue".wlfi.com. Archived fromthe originalon July 4, 2019. RetrievedJuly 5,2019.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 58.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 68–69.

- ^abHansen 2005, p. 71.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 76–79.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 79–85.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 90.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 94.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 92–93.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 95–96.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 112.

- ^ab"Ex-Lieutenant (junior grade) Neil Alden Armstrong, U.S. Naval Reserve, Transcript of Naval Service"(PDF). United States Navy. March 27, 1967.Archived(PDF)from the original on May 6, 2017. RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^abHansen 2005, p. 118.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 61–62.

- ^"Purdue mourns alumnus Neil Armstrong". Purdue University. August 25, 2012.Archivedfrom the original on December 16, 2017. RetrievedApril 2,2018.

- ^"Purdue Bands launch $2 million fund-raising campaign". Purdue University. April 25, 1997. RetrievedJuly 10,2018.

- ^ab"Biographical Data: Neil A. Armstrong". NASA. August 2012. Archived fromthe originalon December 4, 2017. RetrievedApril 7,2018.

- ^"Biography: Neil A. Armstrong". NASA (Glenn Research Center). March 2008.Archivedfrom the original on May 26, 2011. RetrievedMay 16,2011.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 62.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 124–128.

- ^Chillag, Amy; Higgins, Cole (March 1, 2019)."Girl, 7, Fighting Rare Cancer Gets Pics of Dogs from Well-Wishers".CNN. RetrievedNovember 24,2019.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 161–164.

- ^abHansen 2005, pp. 119–120.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 130.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 134.

- ^Creech, Gray (July 15, 2004)."From the Mojave to the Moon: Neil Armstrong's Early NASA Years". NASA. Archived fromthe originalon June 30, 2011. RetrievedMay 17,2011.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 134–136.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 136–138.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 145.

- ^Evans, Michelle (2013)."The X-15 Rocket Plane: Flight Log"(PDF). Mach 25 Media. pp. 22, 25.Archived(PDF)from the original on April 13, 2018. RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 147.

- ^"T. Keith Glennan". NASA. Archived fromthe originalon February 14, 2017. RetrievedMarch 4,2018.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 178–184.

- ^Klesius, Mike (May 20, 2009)."Neil Armstrong's X-15 flight over Pasadena".Smithsonian Air & Space Magazine. RetrievedJanuary 25,2023.

- ^abCollins 2001, pp. 314.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 138–139.

- ^Jenkins 2000, pp. 118–121.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 210.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 184–189.

- ^abHansen 2005, pp. 189–192.

- ^Burgess 2013, pp. 17–18.

- ^Reichhardt, Tony (August–September 2000)."First Up?".Air & Space. RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 171–173.

- ^Burgess 2013, pp. 19–21.

- ^Burgess 2013, pp. 4–6.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 193–195.

- ^abBurgess 2013, pp. 29–30.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 201–202.

- ^Burgess 2013, pp. 64–66.

- ^"Elliot M. See, Jr". NASA. Archived fromthe originalon May 13, 2011. RetrievedMay 19,2011.

- ^Burgess 2013, p. 54.

- ^Reichl 2016, p. 78.

- ^Hacker & Grimwood 2010, pp. 255–256.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 239.

- ^Hacker & Grimwood 2010, pp. 257–258.

- ^abHansen 2005, p. 240.

- ^abHacker & Grimwood 2010, pp. 523–529.

- ^"14 New Astronauts Introduced at Press Conference"(PDF).Space News. Vol. 3, no. 1. October 30, 1963. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on December 22, 2016. RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^"Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova (Born March 6, 1937)". Yaroslavl Regional Government. Archived fromthe originalon September 4, 2015. RetrievedJuly 27,2015.

- ^Hacker & Grimwood 2010, pp. 323–325.

- ^Cunningham 2010, p. 258.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 242–244.

- ^Hacker & Grimwood 2010, p. 526.

- ^"March 16, 1966: Gemini's First Docking of Two Spacecraft in Earth Orbit". NASA. March 16, 2016. RetrievedApril 30,2018.

- ^Merritt, Larry (March 2006)."The abbreviated flight of Gemini 8". Boeing. Archived fromthe originalon August 12, 2011. RetrievedMay 14,2011.

- ^Cunningham 2010, pp. 111–112.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 270–271.

- ^Kranz 2000, p. 174.

- ^abHansen 2005, p. 274.

- ^Hacker & Grimwood 2010, pp. 321–322.

- ^abAgency Awards Historical Recipient List(PDF), NASA,archived(PDF)from the original on December 2, 2016, retrievedFebruary 28,2018

- ^"Serious Problem in Space".The Times Recorder. Zanesville, Ohio. United Press International. March 27, 1966. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^"Valor awards for David Randolph Scott". Military Times Hall of Valor.Archivedfrom the original on March 1, 2018. RetrievedFebruary 28,2018.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 292–293.

- ^"Gemini-XI". NASA (Kennedy Space Center). August 25, 2000. Archived fromthe originalon February 1, 2012. RetrievedJuly 24,2010.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 294–296.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 296–297.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 298–299.

- ^Lovell & Kluger 2000, pp. 24–25.

- ^Cernan & Davis 1999, p. 165.

- ^abHansen 2005, pp. 312–313.

- ^Brooks et al. 2009, p. 374.

- ^Collins 2001, pp. 288–289.

- ^Cunningham 2010, p. 109.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 330.

- ^Kraft 2001, p. 312.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 334.

- ^Chaikin 1994, p. 171.

- ^Chaikin 1994, p. 179.

- ^Nelson 2009, p. 17.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 338.

- ^Collins 2001, pp. 312–313.

- ^Kraft 2001, pp. 323–324.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 365–373.

- ^Cortright 1975, p. 160.

- ^Orloff 2000, p. 92.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 2.

- ^Hansen 2005, p. 410.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 411–412.

- ^Smith 2005, p. 11.

- ^Hansen 2005, pp. 459–465.

- ^Chaikin 1994, p. 199.

- ^Chaikin 1994, p. 198.

- ^abChaikin 1994, p. 200.

- ^Manned Spacecraft Center 1969, pp. 9-23–9-24.

- ^Jones, Eric M."The First Lunar Landing, time 109:45:40".Apollo 11 Surface Journal. NASA. Archived fromthe originalon December 25, 2017. RetrievedMarch 4,2018.That was the time of probe contact; the exact time of landing is difficult to determine, because Armstrong said the landing was "very gentle" and "It was hard to tell when we were on."

- ^Jones, Eric M. (September 15, 2017)."The First Lunar Landing, time 1:02:45".Apollo 11 Surface Journal. NASA. Archived fromthe originalon December 25, 2017. RetrievedNovember 30,2007.

- ^Jones, Eric M."Mission Transcripts, Apollo 11 AS11 PA0.pdf"(PDF).Apollo 11 Surface Journal. NASA. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on September 17, 2008. RetrievedNovember 30,2007.

- ^Jones, Eric M."Apollo 11 Mission Commentary 7-20-69 CDT 15:15 – GET 102:43 – TAPE 307/1".Apollo 11 Surface Journal. NASA. Archived fromthe originalon November 8, 2017.

- ^Manned Spacecraft Center 1969, p. 12-1.

- ^Cortright 1975, p. 215.

- ^Harland 1999, p. 23.

- ^abcdMikkelson, Barbara; Mikkelson, David (October 2006)."One Small Misstep: Neil Armstrong's First Words on the Moon".Snopes.com. RetrievedSeptember 19,2009.

- ^Stern, Jacob (July 23, 2019)."One Small Controversy About Neil Armstrong's Giant Leap".The Atlantic. RetrievedJuly 25,2019.