Mathematical analysis

| Part of a series on | ||

| Mathematics | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

Analysisis the branch ofmathematicsdealing withcontinuous functions,limits, and related theories, such asdifferentiation,integration,measure,infinite sequences,series, andanalytic functions.[1][2]

These theories are usually studied in the context ofrealandcomplexnumbers andfunctions. Analysis evolved fromcalculus, which involves the elementary concepts and techniques of analysis. Analysis may be distinguished fromgeometry; however, it can be applied to anyspaceofmathematical objectsthat has a definition of nearness (atopological space) or specific distances between objects (ametric space).

History

[edit]

Ancient

[edit]Mathematical analysis formally developed in the 17th century during theScientific Revolution,[3]but many of its ideas can be traced back to earlier mathematicians. Early results in analysis were implicitly present in the early days ofancient Greek mathematics. For instance, aninfinite geometric sumis implicit inZeno'sparadox of the dichotomy.[4](Strictly speaking, the point of the paradox is to deny that the infinite sum exists.) Later,Greek mathematicianssuch asEudoxusandArchimedesmade more explicit, but informal, use of the concepts of limits and convergence when they used themethod of exhaustionto compute the area and volume of regions and solids.[5]The explicit use ofinfinitesimalsappears in Archimedes'The Method of Mechanical Theorems, a work rediscovered in the 20th century.[6]In Asia, theChinese mathematicianLiu Huiused the method of exhaustion in the 3rd century CE to find the area of a circle.[7]From Jain literature, it appears that Hindus were in possession of the formulae for the sum of thearithmeticandgeometricseries as early as the 4th century BCE.[8]Ācārya Bhadrabāhuuses the sum of a geometric series in his Kalpasūtra in 433BCE.[9]

Medieval

[edit]Zu Chongzhiestablished a method that would later be calledCavalieri's principleto find the volume of aspherein the 5th century.[10]In the 12th century, theIndian mathematicianBhāskara IIused infinitesimal and used what is now known asRolle's theorem.[11]

In the 14th century,Madhava of Sangamagramadevelopedinfinite seriesexpansions, now calledTaylor series, of functions such assine,cosine,tangentandarctangent.[12]Alongside his development of Taylor series oftrigonometric functions, he also estimated the magnitude of the error terms resulting of truncating these series, and gave a rational approximation of some infinite series. His followers at theKerala School of Astronomy and Mathematicsfurther expanded his works, up to the 16th century.

Modern

[edit]Foundations

[edit]The modern foundations of mathematical analysis were established in 17th century Europe.[3]This began whenFermatandDescartesdevelopedanalytic geometry, which is the precursor to modern calculus. Fermat's method ofadequalityallowed him to determine the maxima and minima of functions and the tangents of curves.[13]Descartes's publication ofLa Géométriein 1637, which introduced theCartesian coordinate system, is considered to be the establishment of mathematical analysis. It would be a few decades later thatNewtonandLeibnizindependently developedinfinitesimal calculus, which grew, with the stimulus of applied work that continued through the 18th century, into analysis topics such as thecalculus of variations,ordinaryandpartial differential equations,Fourier analysis, andgenerating functions. During this period, calculus techniques were applied to approximatediscrete problemsby continuous ones.

Modernization

[edit]In the 18th century,Eulerintroduced the notion of amathematical function.[14]Real analysis began to emerge as an independent subject whenBernard Bolzanointroduced the modern definition of continuity in 1816,[15]but Bolzano's work did not become widely known until the 1870s. In 1821,Cauchybegan to put calculus on a firm logical foundation by rejecting the principle of thegenerality of algebrawidely used in earlier work, particularly by Euler. Instead, Cauchy formulated calculus in terms of geometric ideas andinfinitesimals. Thus, his definition of continuity required an infinitesimal change inxto correspond to an infinitesimal change iny. He also introduced the concept of theCauchy sequence, and started the formal theory ofcomplex analysis.Poisson,Liouville,Fourierand others studied partial differential equations andharmonic analysis. The contributions of these mathematicians and others, such asWeierstrass, developed the(ε, δ)-definition of limitapproach, thus founding the modern field of mathematical analysis. Around the same time,Riemannintroduced his theory ofintegration, and made significant advances in complex analysis.

Towards the end of the 19th century, mathematicians started worrying that they were assuming the existence of acontinuumofreal numberswithout proof.Dedekindthen constructed the real numbers byDedekind cuts, in which irrational numbers are formally defined, which serve to fill the "gaps" between rational numbers, thereby creating acompleteset: the continuum of real numbers, which had already been developed bySimon Stevinin terms ofdecimal expansions. Around that time, the attempts to refine thetheoremsofRiemann integrationled to the study of the "size" of the set ofdiscontinuitiesof real functions.

Also, variouspathological objects, (such asnowhere continuous functions, continuous butnowhere differentiable functions, andspace-filling curves), commonly known as "monsters", began to be investigated. In this context,Jordandeveloped his theory ofmeasure,Cantordeveloped what is now callednaive set theory, andBaireproved theBaire category theorem. In the early 20th century, calculus was formalized using an axiomaticset theory.Lebesguegreatly improved measure theory, and introduced his own theory of integration, now known asLebesgue integration, which proved to be a big improvement over Riemann's.HilbertintroducedHilbert spacesto solveintegral equations. The idea ofnormed vector spacewas in the air, and in the 1920sBanachcreatedfunctional analysis.

Important concepts

[edit]Metric spaces

[edit]Inmathematics, a metric space is asetwhere a notion ofdistance(called ametric) between elements of the set is defined.

Much of analysis happens in some metric space; the most commonly used are thereal line, thecomplex plane,Euclidean space, othervector spaces, and theintegers. Examples of analysis without a metric includemeasure theory(which describes size rather than distance) andfunctional analysis(which studiestopological vector spacesthat need not have any sense of distance).

Formally, a metric space is anordered pairwhereis a set andis ametricon, i.e., afunction

such that for any, the following holds:

- , with equalityif and only if(identity of indiscernibles),

- (symmetry), and

- (triangle inequality).

By taking the third property and letting, it can be shown that(non-negative).

Sequences and limits

[edit]A sequence is an ordered list. Like aset, it containsmembers(also calledelements, orterms). Unlike a set, order matters, and exactly the same elements can appear multiple times at different positions in the sequence. Most precisely, a sequence can be defined as afunctionwhose domain is acountabletotally orderedset, such as thenatural numbers.

One of the most important properties of a sequence isconvergence. Informally, a sequence converges if it has alimit. Continuing informally, a (singly-infinite) sequence has a limit if it approaches some pointx, called the limit, asnbecomes very large. That is, for an abstract sequence (an) (withnrunning from 1 to infinity understood) the distance betweenanandxapproaches 0 asn→ ∞, denoted

Main branches

[edit]Calculus

[edit]Real analysis

[edit]Real analysis (traditionally, the "theory of functions of a real variable") is a branch of mathematical analysis dealing with thereal numbersand real-valued functions of a real variable.[16][17]In particular, it deals with the analytic properties of realfunctionsandsequences, includingconvergenceandlimitsofsequencesof real numbers, thecalculusof the real numbers, andcontinuity,smoothnessand related properties of real-valued functions.

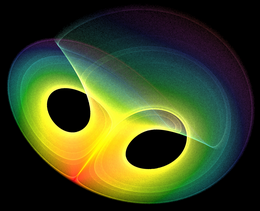

Complex analysis

[edit]Complex analysis (traditionally known as the "theory of functions of a complex variable") is the branch of mathematical analysis that investigatesfunctionsofcomplex numbers.[18]It is useful in many branches of mathematics, includingalgebraic geometry,number theory,applied mathematics; as well as inphysics, includinghydrodynamics,thermodynamics,mechanical engineering,electrical engineering, and particularly,quantum field theory.

Complex analysis is particularly concerned with theanalytic functionsof complex variables (or, more generally,meromorphic functions). Because the separaterealandimaginaryparts of any analytic function must satisfyLaplace's equation, complex analysis is widely applicable to two-dimensional problems inphysics.

Functional analysis

[edit]Functional analysis is a branch of mathematical analysis, the core of which is formed by the study ofvector spacesendowed with some kind of limit-related structure (e.g.inner product,norm,topology, etc.) and thelinear operatorsacting upon these spaces and respecting these structures in a suitable sense.[19][20]The historical roots of functional analysis lie in the study ofspaces of functionsand the formulation of properties of transformations of functions such as theFourier transformas transformations definingcontinuous,unitaryetc. operators between function spaces. This point of view turned out to be particularly useful for the study ofdifferentialandintegral equations.

Harmonic analysis

[edit]Harmonic analysis is a branch of mathematical analysis concerned with the representation offunctionsandsignalsas the superposition of basicwaves. This includes the study of the notions ofFourier seriesandFourier transforms(Fourier analysis), and of their generalizations. Harmonic analysis has applications in areas as diverse asmusic theory,number theory,representation theory,signal processing,quantum mechanics,tidal analysis, andneuroscience.

Differential equations

[edit]A differential equation is amathematicalequationfor an unknownfunctionof one or severalvariablesthat relates the values of the function itself and itsderivativesof variousorders.[21][22][23]Differential equations play a prominent role inengineering,physics,economics,biology, and other disciplines.

Differential equations arise in many areas of science and technology, specifically whenever adeterministicrelation involving some continuously varying quantities (modeled by functions) and their rates of change in space or time (expressed as derivatives) is known or postulated. This is illustrated inclassical mechanics, where the motion of a body is described by its position and velocity as the time value varies.Newton's lawsallow one (given the position, velocity, acceleration and various forces acting on the body) to express these variables dynamically as a differential equation for the unknown position of the body as a function of time. In some cases, this differential equation (called anequation of motion) may be solved explicitly.

Measure theory

[edit]A measure on asetis a systematic way to assign a number to each suitablesubsetof that set, intuitively interpreted as its size.[24]In this sense, a measure is a generalization of the concepts of length, area, and volume. A particularly important example is theLebesgue measureon aEuclidean space, which assigns the conventionallength,area, andvolumeofEuclidean geometryto suitable subsets of the-dimensional Euclidean space. For instance, the Lebesgue measure of theintervalin thereal numbersis its length in the everyday sense of the word – specifically, 1.

Technically, a measure is a function that assigns a non-negative real number or+∞to (certain) subsets of a set. It must assign 0 to theempty setand be (countably) additive: the measure of a 'large' subset that can be decomposed into a finite (or countable) number of 'smaller' disjoint subsets, is the sum of the measures of the "smaller" subsets. In general, if one wants to associate aconsistentsize toeachsubset of a given set while satisfying the other axioms of a measure, one only finds trivial examples like thecounting measure. This problem was resolved by defining measure only on a sub-collection of all subsets; the so-calledmeasurablesubsets, which are required to form a-algebra. This means that the empty set, countableunions, countableintersectionsandcomplementsof measurable subsets are measurable.Non-measurable setsin a Euclidean space, on which the Lebesgue measure cannot be defined consistently, are necessarily complicated in the sense of being badly mixed up with their complement. Indeed, their existence is a non-trivial consequence of theaxiom of choice.

Numerical analysis

[edit]Numerical analysis is the study ofalgorithmsthat use numericalapproximation(as opposed to generalsymbolic manipulations) for the problems of mathematical analysis (as distinguished fromdiscrete mathematics).[25]

Modern numerical analysis does not seek exact answers, because exact answers are often impossible to obtain in practice. Instead, much of numerical analysis is concerned with obtaining approximate solutions while maintaining reasonable bounds on errors.

Numerical analysis naturally finds applications in all fields of engineering and the physical sciences, but in the 21st century, the life sciences and even the arts have adopted elements of scientific computations.Ordinary differential equationsappear incelestial mechanics(planets, stars and galaxies);numerical linear algebrais important for data analysis;stochastic differential equationsandMarkov chainsare essential in simulating living cells for medicine and biology.

Vector analysis

[edit]Vector analysis, also calledvector calculus, is a branch of mathematical analysis dealing withvector-valued functions.[26]

Scalar analysis

[edit]Scalar analysis is a branch of mathematical analysis dealing with values related to scale as opposed to direction. Values such as temperature are scalar because they describe the magnitude of a value without regard to direction, force, or displacement that value may or may not have.

Tensor analysis

[edit]Other topics

[edit]- Calculus of variationsdeals with extremizingfunctionals, as opposed to ordinarycalculuswhich deals withfunctions.

- Harmonic analysisdeals with the representation offunctionsor signals as thesuperpositionof basicwaves.

- Geometric analysisinvolves the use of geometrical methods in the study ofpartial differential equationsand the application of the theory of partial differential equations to geometry.

- Clifford analysis, the study of Clifford valued functions that are annihilated by Dirac or Dirac-like operators, termed in general as monogenic or Clifford analytic functions.

- p-adic analysis, the study of analysis within the context ofp-adic numbers, which differs in some interesting and surprising ways from its real and complex counterparts.

- Non-standard analysis, which investigates thehyperreal numbersand their functions and gives arigoroustreatment ofinfinitesimalsand infinitely large numbers.

- Computable analysis, the study of which parts of analysis can be carried out in acomputablemanner.

- Stochastic calculus– analytical notions developed forstochastic processes.

- Set-valued analysis– applies ideas from analysis and topology to set-valued functions.

- Convex analysis, the study of convex sets and functions.

- Idempotent analysis– analysis in the context of anidempotent semiring, where the lack of an additive inverse is compensated somewhat by the idempotent rule A + A = A.

- Tropical analysis– analysis of the idempotent semiring called thetropical semiring(ormax-plus algebra/min-plus algebra).

- Constructive analysis, which is built upon a foundation ofconstructive, rather than classical, logic and set theory.

- Intuitionistic analysis, which is developed from constructive logic like constructive analysis but also incorporateschoice sequences.

- Paraconsistent analysis, which is built upon a foundation ofparaconsistent, rather than classical, logic and set theory.

- Smooth infinitesimal analysis, which is developed in a smooth topos.

Applications

[edit]Techniques from analysis are also found in other areas such as:

Physical sciences

[edit]The vast majority ofclassical mechanics,relativity, andquantum mechanicsis based on applied analysis, anddifferential equationsin particular. Examples of important differential equations includeNewton's second law, theSchrödinger equation, and theEinstein field equations.

Functional analysisis also a major factor inquantum mechanics.

Signal processing

[edit]When processing signals, such asaudio,radio waves, light waves,seismic waves, and even images, Fourier analysis can isolate individual components of a compound waveform, concentrating them for easier detection or removal. A large family of signal processing techniques consist of Fourier-transforming a signal, manipulating the Fourier-transformed data in a simple way, and reversing the transformation.[27]

Other areas of mathematics

[edit]Techniques from analysis are used in many areas of mathematics, including:

- Analytic number theory

- Analytic combinatorics

- Continuous probability

- Differential entropyin information theory

- Differential games

- Differential geometry, the application of calculus to specific mathematical spaces known asmanifoldsthat possess a complicated internal structure but behave in a simple manner locally.

- Differentiable manifolds

- Differential topology

- Partial differential equations

Famous Textbooks

[edit]- Foundation of Analysis: The Arithmetic of Whole Rational, Irrational and Complex Numbers, by Edmund Landau

- Introductory Real Analysis, byAndrey Kolmogorov,Sergei Fomin[28]

- Differential and Integral Calculus (3 volumes), byGrigorii Fichtenholz[29][30][31]

- The Fundamentals of Mathematical Analysis (2 volumes), byGrigorii Fichtenholz[32][33]

- A Course Of Mathematical Analysis (2 volumes), bySergey Nikolsky[34][35]

- Mathematical Analysis (2 volumes), byVladimir Zorich[36][37]

- A Course of Higher Mathematics (5 volumes, 6 parts), byVladimir Smirnov[38][39][40][41][42]

- Differential And Integral Calculus, byNikolai Piskunov[43]

- A Course of Mathematical Analysis, byAleksandr Khinchin[44]

- Mathematical Analysis: A Special Course, byGeorgiy Shilov[45]

- Theory of Functions of a Real Variable (2 volumes), byIsidor Natanson[46][47]

- Problems in Mathematical Analysis, byBoris Demidovich[48]

- Problems and Theorems in Analysis(2 volumes), byGeorge Pólya,Gábor Szegő[49][50]

- Mathematical Analysis: A Modern Approach to Advanced Calculus, byTom Apostol[51]

- Principles of Mathematical Analysis, byWalter Rudin[52]

- Real Analysis: Measure Theory, Integration, and Hilbert Spaces, byElias Stein[53]

- Complex Analysis: An Introduction to the Theory of Analytic Functions of One Complex Variable, byLars Ahlfors[54]

- Complex Analysis, byElias Stein[55]

- Functional Analysis: Introduction to Further Topics in Analysis, byElias Stein[56]

- Analysis (2 volumes), byTerence Tao[57][58]

- Analysis (3 volumes), by Herbert Amann, Joachim Escher[59][60][61]

- Real and Functional Analysis, by Vladimir Bogachev, Oleg Smolyanov[62]

- Real and Functional Analysis, bySerge Lang[63]

See also

[edit]- Constructive analysis

- History of calculus

- Hypercomplex analysis

- Multiple rule-based problems

- Multivariable calculus

- Paraconsistent logic

- Smooth infinitesimal analysis

- Timeline of calculus and mathematical analysis

References

[edit]- ^Edwin Hewittand Karl Stromberg, "Real and Abstract Analysis", Springer-Verlag, 1965

- ^Stillwell, John Colin."analysis | mathematics".Encyclopædia Britannica.Archivedfrom the original on 2015-07-26. Retrieved2015-07-31.

- ^abJahnke, Hans Niels (2003).A History of Analysis.American Mathematical Society. p. 7.doi:10.1090/hmath/024.ISBN978-0821826232.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-05-17. Retrieved2015-11-15.

- ^Stillwell, John Colin(2004). "Infinite Series".Mathematics and its History(2nd ed.).Springer Science+Business Media Inc.p. 170.ISBN978-0387953366.

Infinite series were present in Greek mathematics, [...] There is no question that Zeno's paradox of the dichotomy (Section 4.1), for example, concerns the decomposition of the number 1 into the infinite series1⁄2+1⁄22+1⁄23+1⁄24+ ... and that Archimedes found the area of the parabolic segment (Section 4.4) essentially by summing the infinite series 1 +1⁄4+1⁄42+1⁄43+ ... =4⁄3. Both these examples are special cases of the result we express as summation of a geometric series

- ^Smith, David Eugene(1958).History of Mathematics.Dover Publications.ISBN978-0486204307.

- ^Pinto, J. Sousa (2004).Infinitesimal Methods of Mathematical Analysis. Horwood Publishing. p. 8.ISBN978-1898563990.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-06-11. Retrieved2015-11-15.

- ^Dun, Liu; Fan, Dainian; Cohen, Robert Sonné (1966).A comparison of Archimedes' and Liu Hui's studies of circles. Chinese studies in the history and philosophy of science and technology. Vol. 130. Springer. p. 279.ISBN978-0-7923-3463-7.Archivedfrom the original on 2016-06-17. Retrieved2015-11-15.,Chapter, p. 279Archived2016-05-26 at theWayback Machine

- ^Singh, A. N. (1936)."On the Use of Series in Hindu Mathematics".Osiris.1: 606–628.doi:10.1086/368443.JSTOR301627.S2CID144760421.

- ^K. B. Basant, Satyananda Panda (2013)."Summation of Convergent Geometric Series and the concept of approachable Sunya"(PDF).Indian Journal of History of Science.48: 291–313.

- ^Zill, Dennis G.; Wright, Scott; Wright, Warren S. (2009).Calculus: Early Transcendentals(3 ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. xxvii.ISBN978-0763759957.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-04-21. Retrieved2015-11-15.

- ^Seal, Sir Brajendranath (1915), "The positive sciences of the ancient Hindus",Nature,97(2426): 177,Bibcode:1916Natur..97..177.,doi:10.1038/097177a0,hdl:2027/mdp.39015004845684,S2CID3958488

- ^Rajagopal, C. T.; Rangachari, M. S. (June 1978). "On an untapped source of medieval Keralese Mathematics".Archive for History of Exact Sciences.18(2): 89–102.doi:10.1007/BF00348142.S2CID51861422.

- ^Pellegrino, Dana."Pierre de Fermat".Archivedfrom the original on 2008-10-12. Retrieved2008-02-24.

- ^Dunham, William (1999).Euler: The Master of Us All. The Mathematical Association of America. p.17.

- ^*Cooke, Roger(1997)."Beyond the Calculus".The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. Wiley-Interscience. p.379.ISBN978-0471180821.

Real analysis began its growth as an independent subject with the introduction of the modern definition of continuity in 1816 by the Czech mathematician Bernard Bolzano (1781–1848)

- ^Rudin, Walter(1976).Principles of Mathematical Analysis. Walter Rudin Student Series in Advanced Mathematics (3rd ed.). McGraw–Hill.ISBN978-0070542358.

- ^Abbott, Stephen (2001).Understanding Analysis. Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics. New York: Springer-Verlag.ISBN978-0387950600.

- ^Ahlfors, Lars Valerian(1979).Complex Analysis(3rd ed.). New York:McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0070006577.

- ^Rudin, Walter(1991).Functional Analysis.McGraw-Hill Science.ISBN978-0070542365.

- ^Conway, John Bligh(1994).A Course in Functional Analysis(2nd ed.).Springer-Verlag.ISBN978-0387972459.Archivedfrom the original on 2020-09-09. Retrieved2016-02-11.

- ^Ince, Edward L. (1956).Ordinary Differential Equations. Dover Publications.ISBN978-0486603490.

- ^Witold Hurewicz,Lectures on Ordinary Differential Equations, Dover Publications,ISBN0486495108

- ^Evans, Lawrence Craig(1998).Partial Differential Equations. Providence:American Mathematical Society.ISBN978-0821807729.

- ^Tao, Terence(2011).An Introduction to Measure Theory. American Mathematical Society.doi:10.1090/gsm/126.ISBN978-0821869192.Archivedfrom the original on 2019-12-27. Retrieved2018-10-26.

- ^Hildebrand, Francis B.(1974).Introduction to Numerical Analysis(2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0070287617.

- ^Borisenko, A. I.; Tarapov, I. E. (1979).Vector and Tensor Analysis with Applications (Dover Books on Mathematics). Dover Books on Mathematics.

- ^Rabiner, L. R.; Gold, B. (1975).Theory and Application of Digital Signal Processing. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey:Prentice-Hall.ISBN978-0139141010.

- ^"Introductory Real Analysis". 1970.

- ^"Курс дифференциального и интегрального исчисления. Том I". 1969.

- ^"Основы математического анализа. Том II". 1960.

- ^"Курс дифференциального и интегрального исчисления. Том III". 1960.

- ^The Fundamentals of Mathematical Analysis: International Series in Pure and Applied Mathematics, Volume 1.ASIN0080134734.

- ^The Fundamentals of Mathematical Analysis: International Series of Monographs in Pure and Applied Mathematics, Vol. 73-II.ASIN1483213153.

- ^"A Course of Mathematical Analysis Vol 1". 1977.

- ^"A Course of Mathematical Analysis Vol 2". 1987.

- ^Mathematical Analysis I.ASIN3662569558.

- ^Mathematical Analysis II.ASIN3662569663.

- ^"A Course of Higher Mathematics Vol 3 1 Linear Algebra". 1964.

- ^"A Course of Higher Mathematics Vol 2 Advanced Calculus". 1964.

- ^"A Course of Higher Mathematics Vol 3-2 Complex Variables Special Functions". 1964.

- ^"A Course of Higher Mathematics Vol 4 Integral and Partial Differential Equations". 1964.

- ^"A Course of Higher Mathematics Vol 5 Integration and Functional Analysis". 1964.

- ^"Differential and Integral Calculus". 1969.

- ^"A Course of Mathematical Analysis". 1960.

- ^Mathematical Analysis: A Special Course.ASIN1483169561.

- ^"Theory of functions of a real variable (Teoria functsiy veshchestvennoy peremennoy, chapters I to IX)". 1955.

- ^"Theory of functions of a real variable =Teoria functsiy veshchestvennoy peremennoy". 1955.

- ^"Problems in Mathematical Analysis". 1970.

- ^Problems and Theorems in Analysis I: Series. Integral Calculus. Theory of Functions.ASIN3540636404.

- ^Problems and Theorems in Analysis II: Theory of Functions. Zeros. Polynomials. Determinants. Number Theory. Geometry.ASIN3540636862.

- ^Mathematical Analysis: A Modern Approach to Advanced Calculus, 2nd Edition.ASIN0201002884.

- ^Principles of Mathematical Analysis.ASIN0070856133.

- ^Real Analysis: Measure Theory, Integration, and Hilbert Spaces.ASIN0691113866.

- ^Complex Analysis: An Introduction to the Theory of Analytic Functions of One Complex Variable. 1979-01-01.ISBN978-0070006577.

- ^Complex Analysis.ASIN0691113858.

- ^Functional Analysis: Introduction to Further Topics in Analysis.ASIN0691113874.

- ^Analysis I: Third Edition.ASIN9380250649.

- ^Analysis II: Third Edition.ASIN9380250657.

- ^Amann, Herbert; Escher, Joachim (2004).Analysis I.ISBN978-3764371531.

- ^Amann, Herbert; Escher, Joachim (2008-05-16).Analysis II.ISBN978-3764374723.

- ^Amann, Herbert; Escher, Joachim (2009).Analysis III.ISBN978-3764374792.

- ^Bogachev, Vladimir I.; Smolyanov, Oleg G. (2021).Real and Functional Analysis.ISBN978-3030382216.

- ^Lang, Serge (2012).Real and Functional Analysis.ISBN978-1461269380.

Further reading

[edit]- Aleksandrov, A. D.;Kolmogorov, A. N.;Lavrent'ev, M. A., eds. (March 1969).Mathematics: Its Content, Methods, and Meaning. Vol. 1–3. Translated by Gould, S. H. (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts:The M.I.T. Press/American Mathematical Society.

- Apostol, Tom M.(1974).Mathematical Analysis(2nd ed.).Addison–Wesley.ISBN978-0201002881.

- Binmore, Kenneth George(1981) [1981].The foundations of analysis: a straightforward introduction.Cambridge University Press.

- Johnsonbaugh, Richard; Pfaffenberger, William Elmer (1981).Foundations of mathematical analysis. New York:M. Dekker.

- Nikol'skiĭ [Нико́льский], Sergey Mikhailovich [Серге́й Миха́йлович](2002)."Mathematical analysis". InHazewinkel, Michiel(ed.).Encyclopaedia of Mathematics.Springer-Verlag.ISBN978-1402006098.

- Fusco, Nicola;Marcellini, Paolo; Sbordone, Carlo (1996).Analisi Matematica Due(in Italian).Liguori Editore.ISBN978-8820726751.

- Rombaldi, Jean-Étienne (2004).Éléments d'analyse réelle : CAPES et agrégation interne de mathématiques(in French).EDP Sciences.ISBN978-2868836816.

- Rudin, Walter(1976).Principles of Mathematical Analysis(3rd ed.). New York:McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0070542358.

- Rudin, Walter(1987).Real and Complex Analysis(3rd ed.). New York:McGraw-Hill.ISBN978-0070542341.

- Whittaker, Edmund Taylor;Watson, George Neville(1927-01-02).A Course Of Modern Analysis: An Introduction to the General Theory of Infinite Processes and of Analytic Functions; with an Account of the Principal Transcendental Functions(4th ed.). Cambridge:at the University Press.ISBN0521067944.(vi+608 pages) (reprinted: 1935, 1940, 1946, 1950, 1952, 1958, 1962, 1963, 1992)

- "Real Analysis – Course Notes"(PDF).Archived(PDF)from the original on 2007-04-19.

![{\displaystyle \left[0,1\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c57121c2b6c63c0b2f38eb96b1f7a543b5d1c522)