Oxford

|

Oxford

|

|

|---|---|

| Nickname:

City of dreaming spires

|

|

| Motto(s): | |

Oxford shown within

Oxfordshire

|

|

| Coordinates: 51°45′7″N 1°15′28″W / 51.75194°N 1.25778°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | England |

| Region | South East |

| County | Oxfordshire |

| Founded | 8th century |

| City status | 1542 |

| Administrative HQ | Oxford Town Hall |

| Government | |

| • Type | Non-metropolitan district |

| • Body | Oxford City Council |

| • Executive | Leader and cabinet |

| • Control | No overall control |

| • Leader | Susan Brown (L) |

| • Lord Mayor | Mike Rowley |

| • MPs | |

| Area | |

|

• Total

|

18 sq mi (46 km2) |

| • Rank | 248th |

| Population

(2022)

[3]

|

|

|

• Total

|

163,257 |

| • Rank | 126th |

| • Density | 9,300/sq mi (3,580/km2) |

| Demonym | Oxonian |

| Ethnicity (2021) | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| Religion (2021) | |

| • Religion |

List

|

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Postcode areas |

OX1–4

|

| Dialling codes | 01865 |

| GSS code | E07000178 |

| Website | oxford |

Oxford (/ˈɒksfərd/ ⓘ)[5][6] is a cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the oldest university in the English-speaking world;[7] it has buildings in every style of English architecture since late Anglo-Saxon. Oxford's industries include motor manufacturing, education, publishing, science, and information technologies.

Founded in the 8th century, it was granted city status in 1542. The city is located at the confluence of the rivers Thames (locally known as the Isis) and Cherwell. It had a population of 163,257 in 2022.[3] It is 56 miles (90 km) north-west of London, 64 miles (103 km) south-east of Birmingham and 61 miles (98 km) north-east of Bristol.

History

[edit]The history of Oxford in England dates back to its original settlement in the Saxon period. The name “Oxford” comes from the Old English Oxenaforda, meaning “ford of the oxen,” referring to a shallow crossing in the river where oxen could pass.[8] The town was of strategic significance, because of the ford and the town's controlling location on the upper reaches of the River Thames at its confluence with the River Cherwell

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, Norman lord Robert D’Oyly built Oxford Castle in 1071 to secure control of the area.[8] The town grew in national importance during the early Norman period.

Teaching began in the 11th century and by the late 12th century the town was home to the fledgling University of Oxford.[9] Tensions sometimes erupted between the scholastic community and the town: in 1209, after a townsperson hanged two scholars for an alleged murder, a number of Oxford academics fled and founded Cambridge University. Town-and-gown conflicts continued, culminating in the St. Scholastica Day Riot of 1355 – a feuding that lasted days and left around 93 students and townspeople dead.

Oxford was besieged during The Anarchy in 1142.[10] During the Middle Ages, Oxford had an important Jewish community, of which David of Oxford and his wife Licoricia of Winchester were prominent members.[11] The university rose to dominate the town.

A heavily ecclesiastical town, Oxford was greatly affected by the changes of the English Reformation. Oxford’s ecclesiastical institutions were dismantled — the city’s monasteries were closed in the 1530s.[12] Religious strife touched Oxford directly during the Marian persecution: the Oxford Martyrs were tried for heresy here. Bishops Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley were burned at the stake in Oxford in October 1555, and the former Archbishop Thomas Cranmer was executed in March 1556. A Victorian-era monument, the Martyrs’ Memorial in St Giles’, now commemorates these events.

Oxford was elevated from town to city status in 1542 when the Diocese of Oxford was created – Christ Church college chapel was made a cathedral, officially granting Oxford its city privileges.

During the English Civil War (1642–1646), Charles I made Oxford his de facto capital: he moved his court to Oxford, using the city as his headquarters after being expelled from London.[13]

The city began to grow industrially during the 19th century, and had an industrial boom in the early 20th century. Traditional industries included brewing and publishing – Oxford University Press and other print houses were major employers by the 19th century. In 1910 entrepreneur William Morris (later Lord Nuffield) founded a motor car business in Oxford, opening an assembly plant at Cowley.

The city’s population and economy grew with this industrial boom, diversifying beyond the university.

Geography

[edit]Physical

[edit]Location

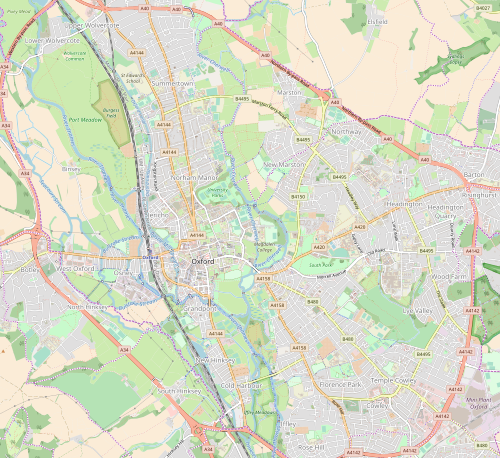

[edit]Oxford's latitude and longitude are 51°45′07″N 1°15′28″W / 51.75194°N 1.25778°W, with Ordnance Survey grid reference SP513061 (at Carfax Tower, which is usually considered the centre). Oxford is 24 miles (39 km) north-west of Reading, 26 miles (42 km) north-east of Swindon, 36 miles (58 km) east of Cheltenham, 43 miles (69 km) east of Gloucester, 29 miles (47 km) south-west of Milton Keynes, 38 miles (61 km) south-east of Evesham, 43 miles (69 km) south of Rugby and 51 miles (82 km) west-north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames (also sometimes known as the Isis locally, supposedly from the Latinised name Thamesis) run through Oxford and meet south of the city centre. These rivers and their flood plains constrain the size of the city centre.

Climate

[edit]Oxford has a maritime temperate climate (Köppen: Cfb). Precipitation is uniformly distributed throughout the year and is provided mostly by weather systems that arrive from the Atlantic. The lowest temperature ever recorded in Oxford was −17.8 °C (0.0 °F) on 24 December 1860. The highest temperature ever recorded in Oxford is 38.1 °C (101 °F) on 19 July 2022.[14] The average conditions below are from the Radcliffe Meteorological Station. It has the longest series of temperature and rainfall records for one site in Britain. These records are continuous from January 1815. Irregular observations of rainfall, cloud cover, and temperature exist since 1767.[15]

The driest year on record was 1788, with 336.7 mm (13.26 in) of rainfall. The wettest year was 2012, with 979.5 mm (38.56 in). The wettest month on record was September 1774, with a total fall of 223.9 mm (8.81 in). The warmest month on record is July 1983, with an average of 21.1 °C (70 °F) and the coldest is January 1963, with an average of −3.0 °C (27 °F). The warmest year on record is 2014, with an average of 11.8 °C (53 °F) and the coldest is 1879, with a mean temperature of 7.7 °C (46 °F). The sunniest month on record is May 2020, with 331.7 hours and December 1890 is the least sunny, with 5.0 hours. The greatest one-day rainfall occurred on 10 July 1968, with a total of 87.9 mm (3.46 in). The greatest known snow depth was 61.0 cm (24.0 in) in February 1888.[16]

| Climate data for Oxford (RMS),[a] elevation: 200 ft (61 m), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1815–2020 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.9 (60.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

30.6 (87.1) |

34.3 (93.7) |

38.1 (100.6) |

35.1 (95.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

38.1 (100.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.0 (46.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.9 (46.2) |

5.4 (41.7) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.3 (36.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.3 (41.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.1 (55.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

8.0 (46.4) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.6 (2.1) |

−16.2 (2.8) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

0.4 (32.7) |

2.4 (36.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−3.3 (26.1) |

−5.7 (21.7) |

−10.1 (13.8) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

−17.8 (0.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 59.6 (2.35) |

46.8 (1.84) |

43.2 (1.70) |

48.7 (1.92) |

56.9 (2.24) |

49.7 (1.96) |

52.5 (2.07) |

61.7 (2.43) |

51.9 (2.04) |

73.2 (2.88) |

71.5 (2.81) |

66.1 (2.60) |

681.6 (26.83) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.1 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 8.9 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 8.3 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 10.9 | 11.3 | 12.2 | 117.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 63.4 | 81.9 | 118.2 | 165.6 | 200.3 | 197.1 | 212.0 | 193.3 | 145.3 | 110.2 | 70.8 | 57.6 | 1,615.5 |

| Source 1: Met Office[17] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: University of Oxford[18] | |||||||||||||

- ^ Weather station is located 0.7 miles (1.1 km) from the Oxford city centre.

Districts

[edit]The city centre

[edit]The city centre is relatively small and is centred on Carfax, a crossroads which forms the junction of Cornmarket Street (pedestrianised), Queen Street (mainly pedestrianised), St Aldate's and the High Street ("the High"; blocked for through traffic). Cornmarket Street and Queen Street are home to Oxford's chain stores, as well as a small number of independent retailers, one of the longest established of which was Boswell's, founded in 1738.[19] The store closed in 2020.[20] St Aldate's has few shops but several local government buildings, including the town hall, the city police station and local council offices. The High (the word street is traditionally omitted) is the longest of the four streets and has a number of independent and high-end chain stores, but mostly university and college buildings. The historic buildings mean the area is often used by film and TV crews.

Suburbs

[edit]Aside from the city centre, there are several suburbs and neighbourhoods within the borders of the city of Oxford, including:

Green belt

[edit]

Oxford is at the centre of the Oxford Green Belt, which is an environmental and planning policy that regulates the rural space in Oxfordshire surrounding the city, aiming to prevent urban sprawl and minimize convergence with nearby settlements.[21] The policy has been blamed for the large rise in house prices in Oxford, making it the least affordable city in the United Kingdom outside of London, with some estate agents calling for brownfield land inside the green belt to be released for new housing.[22][23][24]

The vast majority of the area covered is outside of the city, but there are some green spaces within that which are covered by the designation, such as much of the Thames and river Cherwell flood-meadows, and the village of Binsey, along with several smaller portions on the fringes. Other landscape features and places of interest covered include Cutteslowe Park and the mini railway attraction, the University Parks, Hogacre Common Eco Park, numerous sports grounds, Aston's Eyot, St Margaret's Church and well, and Wolvercote Common and community orchard.[25]

Governance

[edit]

There are two tiers of local government covering Oxford, at district and county level: Oxford City Council and Oxfordshire County Council. From 1889 to 1974 the city of Oxford was a county borough, independent from the county council.[26] Oxford City Council meets at the Town Hall on the street called St Aldate's in the city centre. The current building was completed in 1897, on a site which had been occupied by Oxford's guildhall since the 13th century.[27]

Most of Oxford is an unparished area, but there are four civil parishes within the city's boundaries: Blackbird Leys, Littlemore, Old Marston, and Risinghurst and Sandhills.[28]

Economy

[edit]Oxford's economy includes manufacturing, publishing and science-based industries as well as education, sports, entertainment, breweries, research and tourism.[29]

Car production

[edit]Oxford has been an important centre of motor manufacturing since Morris Motors was established in the city in 1910. The principal production site for Mini cars, owned by BMW since 2000, is in the Oxford suburb of Cowley. The plant, which survived the turbulent years of British Leyland in the 1970s and was threatened with closure in the early 1990s, also produced cars under the Austin and Rover brands following the demise of the Morris brand in 1984, although the last Morris-badged car was produced there in 1982.[citation needed]

Publishing

[edit]Oxford University Press, a department of the University of Oxford, is based in the city, although it no longer operates its own paper mill and printing house. The city is also home to the UK operations of Wiley-Blackwell, Elsevier[30] and several smaller publishing houses.

Science and technology

[edit]The presence of the university has given rise to many science and technology based businesses, including Oxford Instruments, Research Machines and Sophos. The university established Isis Innovation in 1987 to promote technology transfer. The Oxford Science Park was established in 1990, and the Begbroke Science Park, owned by the university, lies north of the city. Oxford increasingly has a reputation for being a centre of digital innovation, as epitomized by Digital Oxford.[31] Several startups including Passle,[32] Brainomix,[33] Labstep,[34] and more, are based in Oxford.

Education

[edit]

The presence of the university has also led to Oxford becoming a centre for the education industry. Companies often draw their teaching staff from the pool of Oxford University students and graduates, and, especially for EFL education, use their Oxford location as a selling point.[35]

Tourism

[edit]

Oxford has numerous major tourist attractions, many belonging to the university and colleges. As well as several famous institutions, the town centre is home to Carfax Tower and the University Church of St Mary the Virgin, both of which offer views over the spires of the city. Many tourists shop at the historic Covered Market. In the summer, punting on the Thames/Isis and the Cherwell is a common practice. As well as being a major draw for tourists (9.1 million in 2008, similar in 2009)[needs update],[36] Oxford city centre has many shops, several theatres and an ice rink.

Retail

[edit]

There are two small shopping malls in the city centre: the Clarendon Centre[37] and the Westgate Oxford.[38] The Westgate Centre is named for the original West Gate in the city wall, and is at the west end of Queen Street. A major redevelopment and expansion to 750,000 sq ft (70,000 m2), with a new 230,000 sq ft (21,000 m2) John Lewis department store and a number of new homes, was completed in October 2017. Blackwell's Bookshop is a bookshop which claims the largest single room devoted to book sales in the whole of Europe, the Norrington Room (10,000 sq ft).[39]

Brewing

[edit]There is a long history of brewing in Oxford. Several of the colleges had private breweries, one of which, at Brasenose, survived until 1889. In the 16th century brewing and malting appear to have been the most popular trades in the city. There were breweries in Brewer Street and Paradise Street, near the Castle Mill Stream. The rapid expansion of Oxford and the development of its railway links after the 1840s facilitated expansion of the brewing trade.[40] As well as expanding the market for Oxford's brewers, railways enabled brewers further from the city to compete for a share of its market.[40] By 1874 there were nine breweries in Oxford and 13 brewers' agents in Oxford shipping beer in from elsewhere.[40] The nine breweries were: Flowers & Co in Cowley Road, Hall's St Giles Brewery, Hall's Swan Brewery (see below), Hanley's City Brewery in Queen Street, Le Mills's Brewery in St. Ebbes, Morrell's Lion Brewery in St Thomas Street (see below), Simonds's Brewery in Queen Street, Weaving's Eagle Brewery (by 1869 the Eagle Steam Brewery) in Park End Street and Wootten and Cole's St. Clement's Brewery.[40]

The Swan's Nest Brewery, later the Swan Brewery, was established by the early 18th century in Paradise Street, and in 1795 was acquired by William Hall.[41] The brewery became known as Hall's Oxford Brewery, which acquired other local breweries. Hall's Brewery was acquired by Samuel Allsopp & Sons in 1926, after which it ceased brewing in Oxford.[42] Morrell's was founded in 1743 by Richard Tawney. He formed a partnership in 1782 with Mark and James Morrell, who eventually became the owners.[43] After an acrimonious family dispute the brewery was closed in 1998.[44] The beer brand names were taken over by the Thomas Hardy Burtonwood brewery,[45] while the 132 tied pubs were bought by Michael Cannon, owner of the American hamburger chain Fuddruckers, through a new company, Morrells of Oxford.[46] The new owners sold most of the pubs on to Greene King in 2002.[47] The Lion Brewery was converted into luxury apartments in 2002.[48] Oxford's first legal distillery, the Oxford Artisan Distillery, was established in 2017 in historic farm buildings at the top of South Park.[49]

Bellfounding

[edit]The Taylor family of Loughborough had a bell-foundry in Oxford between 1786 and 1854.[50]

Buildings

[edit]

This is a small selection of the many notable buildings in Oxford.

- Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford

- The Headington Shark

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Botanic Garden

- Sheldonian Theatre

- St. Mary the Virgin Church

- Radcliffe Camera

- Radcliffe Observatory

- Oxford Oratory

- Malmaison Hotel, in a converted prison in part of the medieval Oxford Castle

Parks and nature walks

[edit]Oxford is a very green city, with several parks and nature walks within the ring road, as well as several sites just outside the ring road. In total, 28 nature reserves exist within or just outside the ring road, including:

Demography

[edit]

As of 2023, Oxford’s population was approximately 165,200.[51] More than a third (35%) of Oxford's residents were born outside of the United Kingdom.[51]

Oxford’s population is notably young and diverse. About 30% of residents are ages 18–29, roughly double the national average for that age bracket. This is largely because of the substantial student population: about 35,000 students are enrolled for full-time studies in the city's two universities.[51]

Ethnicity

[edit]| Ethnic Group | 1981 estimates[52] | 1991[53] | 2001[54] | 2011[55] | 2021[56] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 83,762 | 93% | 99,935 | 90.8% | 116,948 | 87.1% | 117,957 | 77.7% | 120,509 | 70.7% |

| White: British | – | – | – | – | 103,041 | 76.8% | 96,633 | 63.6% | 86,672 | 53.5% |

| White: Irish | – | – | – | – | 2,898 | 2,431 | 2,351 | |||

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | – | – | – | – | 92 | 62 | ||

| White: Roma | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 501 | |

| White: Other | – | – | – | – | 11,009 | 8.2% | 18,801 | 12.4% | 24,975 | 15.4% |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | – | – | 5,808 | 5.3% | 8,931 | 6.7% | 18,827 | 12.4% | 24,991 | 15.4% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | – | – | 1,560 | 1.4% | 2,323 | 1.7% | 4,449 | 2.9% | 6,005 | 3.7% |

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | – | – | 2042 | 1.9% | 2,625 | 2.0% | 4,825 | 3.2% | 6,619 | 4.1% |

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | – | – | 510 | 0.5% | 878 | 0.7% | 1,791 | 1.2% | 2,025 | 1.3% |

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | – | – | 859 | 0.8% | 2,460 | 1.8% | 3,559 | 2.3% | 4,479 | 2.8% |

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | – | – | 837 | 0.8% | 645 | 0.5% | 4,203 | 2.8% | 5,863 | 3.6% |

| Black or Black British: Total | – | – | 3,055 | 2.8% | 3,368 | 2.5% | 7,028 | 4.6% | 7,535 | 4.7% |

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | – | – | 1745 | 1,664 | 1,874 | 1,629 | ||||

| Black or Black British: African | – | – | 593 | 1,408 | 4,456 | 5,060 | ||||

| Black or Black British: Other Black | – | – | 717 | 296 | 698 | 846 | ||||

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | – | – | 3,239 | 2.4% | 6,035 | 4% | 9,005 | 5.6% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | – | – | 1,030 | 1,721 | 1,916 | |||

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | – | – | 380 | 703 | 1,072 | |||

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | – | – | 974 | 2,008 | 3,197 | |||

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | – | – | 855 | 1,603 | 2,820 | |||

| Other: Total | – | – | 1,305 | 1.2% | 1,762 | 1.3% | 2,059 | 1.4% | 5,948 | 3.7% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | – | – | 922 | 0.6% | 1,449 | 0.9% |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | – | – | 1,305 | 1.2% | 1,762 | 1.3% | 1,137 | 0.7% | 4,499 | 2.8% |

| Ethnic minority: Total | 6,265 | 7% | 10,168 | 9.2% | 17,300 | 12.9% | 33,949 | 22.3% | 47,479 | 29.3% |

| Total | 90,027 | 100% | 110,103 | 100% | 134,248 | 100% | 151,906 | 100% | 162,040 | 100% |

Religion

[edit]| Religion | 2001[57] | 2011[58] | 2021[59] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| No religion | 32,075 | 23.9 | 50,274 | 33.1 | 63,201 | 39.0 |

| Christian | 81,100 | 60.4 | 72,924 | 48.0 | 61,750 | 38.1 |

| Religion not stated | 11,725 | 8.7 | 12,611 | 8.3 | 16,110 | 9.9 |

| Muslim | 5,165 | 3.8 | 10,320 | 6.8 | 14,093 | 8.7 |

| Hindu | 1,041 | 0.8 | 2,044 | 1.3 | 2,523 | 1.6 |

| Other religion | 656 | 0.5 | 796 | 0.5 | 1,447 | 0.9 |

| Buddhism | 1,080 | 0.8 | 1,431 | 0.9 | 1,195 | 0.7 |

| Jewish | 1,091 | 0.8 | 1,072 | 0.7 | 1,120 | 0.7 |

| Sikh | 315 | 0.2 | 434 | 0.3 | 599 | 0.4 |

| Total | 134,248 | 100.0% | 151,906 | 100.0% | 162,040 | 100.0% |

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]In addition to the larger airports in the region, Oxford is served by nearby Oxford Airport, in Kidlington. The airport is also home to CAE Oxford Aviation Academy and Airways Aviation[60] airline pilot flight training centres, and several private jet companies. The airport is also home to Airbus Helicopters UK headquarters.[61]

Rail–airport links

[edit]Direct trains run from Oxford railway station to London Paddington where there is an interchange with the Heathrow Express. Passengers can change at Reading for connecting trains to Gatwick Airport or the RailAir coach link to Heathrow. CrossCountry runs direct services to Birmingham International, as well as to Southampton Airport Parkway further afield.

Buses

[edit]

Bus services in Oxford and its suburbs are run by the Oxford Bus Company and Stagecoach West as well as other operators including Arriva Shires & Essex and Thames Travel. Oxford has one of the largest urban park and ride networks in the United Kingdom. Its five sites, at Pear Tree, Redbridge, Seacourt, Thornhill, Water Eaton and Oxford Parkway have a combined capacity of 4,930 car parking spaces,[62] served by 20 Oxford Bus Company double decker buses with a combined capacity of 1,695 seats.[63] Hybrid buses began to be used in Oxford in 2010, and their usage has been expanded.[64] In 2014 Oxford Bus introduced a fleet of 20 new buses with flywheel energy storage on the services it operates under contract for Oxford Brookes University.[65] Most buses in the city now use a smartcard to pay for journeys[66] and have free WiFi installed.[67][68][69]

Coach

[edit]The Oxford to London coach route offers a frequent coach service to London. The Oxford Tube is operated by Stagecoach West and the Oxford Bus Company runs the Airline services to Heathrow and Gatwick airports. There is a bus station at Gloucester Green, used mainly by the London and airport buses, National Express coaches and other long-distance buses including route X5 to Milton Keynes and Bedford and Stagecoach Gold route S6.

Cycling

[edit]Among cities in England and Wales, Oxford has the second highest percentage of people cycling to work.[70]

Rail

[edit]

Oxford railway station is half a mile (about 1 km) west of the city centre. The station is served by trains from three train operating companies. Great Western Railway (GWR) manage the station and run direct services to London Paddington and Worcester, Malvern and Hereford. CrossCountry trains call at Oxford on their Bournemouth—Manchester route via Southampton, Reading and Birmingham. Chiltern Railways operates a service to London Marylebone and will operate the East West Rail trains to Milton Keynes when these start running in 2025.

Oxford has had three main railway stations. The first was opened at Grandpont in 1844,[71] but this was a terminus, inconvenient for routes to the north;[72] it was replaced by the present station on Park End Street in 1852 with the opening of the Birmingham route.[73] Another terminus, at Rewley Road, was opened in 1851 to serve the Bletchley route;[74] this station closed in 1951.[75] There have also been a number of local railway stations, all of which are now closed. A fourth station, Oxford Parkway, is just outside the city, at the park and ride site near Kidlington. The present railway station opened in 1852.

Oxford is the junction for a short branch line to Bicester, a remnant of the former Varsity line to Cambridge. This Oxford–Bicester line was upgraded to 100 mph (161 km/h) running during an 18-month closure in 2014/2015 – and is scheduled to be extended to form the planned East West Rail line to Milton Keynes.[76] East West Rail is proposed to continue through Bletchley (for Milton Keynes Central) to Bedford,[77] Cambridge,[78] and ultimately Ipswich and Norwich,[79] thus providing alternative route to East Anglia without needing to travel via, and connect between, the London mainline terminals.

Chiltern Railways operates from Oxford to London Marylebone via Bicester Village, having sponsored the building of about 400 metres of new track between Bicester Village and the Chiltern Main Line southwards in 2014. The route serves High Wycombe and London Marylebone, avoiding London Paddington and Didcot Parkway.

In 1844, the Great Western Railway linked Oxford with London Paddington via Didcot and Reading;[80][81] in 1851, the London & North Western Railway opened its own route from Oxford to London Euston, via Bicester, Bletchley and Watford;[82] and in 1864 a third route, also to Paddington, running via Thame, High Wycombe and Maidenhead, was provided;[83] this was shortened in 1906 by the opening of a direct route between High Wycombe and London Paddington by way of Denham.[84] The distance from Oxford to London was 78 miles (125.5 km) via Bletchley; 63.5 miles (102.2 km) via Didcot and Reading; 63.25 miles (101.8 km) via Thame and Maidenhead;[85] and 55.75 miles (89.7 km) via Denham.[84]

Only the original (Didcot) route is still in use for its full length, portions of the others remain. There were also routes to the north and west. The line to Banbury was opened in 1850,[72] and was extended to Birmingham Snow Hill in 1852;[73] a route to Worcester opened in 1853.[86] A branch to Witney was opened in 1862,[87] which was extended to Fairford in 1873.[88] The line to Witney and Fairford closed in 1962, but the others remain open.

River and canal

[edit]Oxford was historically an important port on the River Thames, with this section of the river being called the Isis; the Oxford-Burcot Commission in the 17th century attempted to improve navigation to Oxford.[89] Iffley Lock and Osney Lock lie within the bounds of the city. In the 18th century the Oxford Canal was built to connect Oxford with the Midlands.[90] Commercial traffic has given way to recreational use of the river and canal. Oxford was the original base of Salters Steamers (founded in 1858), which was a leading racing-boatbuilder that played an important role in popularising pleasure boating on the Upper Thames. The firm runs a regular service from Folly Bridge downstream to Abingdon and beyond.

Roads

[edit]

Oxford's central location on several transport routes means that it has long been a crossroads city with many coaching inns, although road traffic is now strongly discouraged, and largely prevented, from using the city centre. The Oxford Ring Road or A4142 (southern part) surrounds the city centre and close suburbs Marston, Iffley, Cowley and Headington; it consists of the A34 to the west, a 330-yard section of the A44, the A40 north and north-east, A4142/A423 to the east. It is a dual carriageway, except for a 330-yard section of the A40 where two residential service roads adjoin, and was completed in 1966.

A roads

[edit]The main roads to/from Oxford are:

- A34 – a trunk route connecting the North and Midlands to the port of Southampton. It leaves J9 of the M40 north of Oxford, passes west of Oxford to Newbury and Winchester to the south and joins the M3 12.7 miles (20.4 km) north of Southampton. Since the completion of the Newbury bypass in 1998, this section of the A34 has been an entirely grade separated dual carriageway. Historically the A34 led to Bicester, Banbury, Stratford-upon-Avon, Birmingham and Manchester, but since the completion of the M40 it disappears at J9 and re-emerges 50 miles (80 km) north at Solihull.

- A40 – leading east dualled to J8 of the M40 motorway, then an alternative route to High Wycombe and London; leading west part-dualled to Witney then bisecting Cheltenham, Gloucester, Monmouth, Abergavenny, passing Brecon, Llandovery, Carmarthen and Haverfordwest to reach Fishguard.

- A44 – which begins in Oxford, leading past Evesham to Worcester, Hereford and Aberystwyth.

- A420 – which also begins in Oxford and leads to Bristol, passing Swindon and Chippenham.

Zero-emission zone

[edit]On 28 February 2022 a zero-emission pilot area became operational in Oxford city centre. Zero-emission vehicles can be used without incurring a charge but all petrol and diesel vehicles (including hybrids) incur a daily charge if they are driven in the zone between 7am and 7pm.[91]

A consultation on the introduction of a wider zero-emission zone is expected in the future, at a date to be confirmed.

Bus gates

[edit]Oxford has eight bus gates, short sections of road where only buses and other authorised vehicles can pass.[92]

Six further bus gates are currently proposed. A council-led consultation on the traffic filters ended on 13 October 2022. On 29 November 2022, Oxfordshire County Council cabinet approved the introduction on a trial basis, for a minimum period of six months.[93] The trial will begin after improvement works to Oxford railway station are complete, which is expected to be by October 2024.[94] The additional bus gates have been controversial; Oxford University and Oxford Bus Company support the proposals but more than 3,700 people have signed an online petition opposing the new traffic filters for Marston Ferry Road and Hollow Way, and hotelier Jeremy Mogford has argued they would be a mistake.[95][96] In November 2022, Mogford announced that his hospitality group The Oxford Collection had joined up with Oxford Business Action Group (OBAG), Oxford High Street Association (OHSA), ROX (Backing Oxford Business), Reconnecting Oxford, Jericho Traders, and Summertown traders to launch a legal challenge to the new bus gates.[97]

Motorway

[edit]The city is served by the M40 motorway, which connects London to Birmingham. The M40 approached Oxford in 1974, leading from London to Waterstock, where the A40 continued to Oxford. When the M40 extension to Birmingham was completed in January 1991, it curved sharply north, and a mile of the old motorway became a spur. The M40 comes no closer than 6 miles (10 km) away from the city centre, curving to pass to the east of Otmoor. The M40 meets the A34 to the north of Oxford.

Education

[edit]Schools

[edit]Universities and colleges

[edit]

There are two universities in Oxford, the University of Oxford and Oxford Brookes University, as well as the specialist further and higher education institution Ruskin College that is part of the University of West London in Oxford. The Islamic Azad University also has a campus near Oxford. The University of Oxford is the oldest university in the English-speaking world,[98] and one of the most prestigious higher education institutions of the world, averaging nine applications to every available place, and attracting 40% of its academic staff and 17% of undergraduates from overseas.[99] In September 2016, it was ranked as the world's number one university, according to the Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[100] Oxford is renowned for its tutorial-based method of teaching.

The Bodleian Library

[edit]The University of Oxford maintains the largest university library system in the United Kingdom,[101] and, with over 11 million volumes housed on 120 miles (190 km) of shelving, the Bodleian group is the second-largest library in the United Kingdom, after the British Library. The Bodleian Library is a legal deposit library, which means that it is entitled to request a free copy of every book published in the United Kingdom. As such, its collection is growing at a rate of over three miles (five kilometres) of shelving every year.[102]

Media

[edit]As well as the BBC national radio stations, Oxford and the surrounding area has several local stations, including BBC Radio Oxford, Heart South, First FM (formerly Destiny 105), Greatest Hits Radio and Hits Radio Oxfordshire, along with Oxide: Oxford Student Radio[103] (which went on terrestrial radio at 87.7 MHz FM in late May 2005). A local TV station, Six TV: The Oxford Channel, was also available[104] but closed in April 2009; a service operated by That's TV, originally called That's Oxford (now That's Oxfordshire), took to the airwaves in 2015.[105] The city is home to a BBC Television newsroom which produces an opt-out from the main South Today programme broadcast from Southampton.

Local papers include The Oxford Times (compact; weekly), its sister papers the Oxford Mail (tabloid; daily) and the Oxford Star (tabloid; free and delivered), and Oxford Journal (tabloid; weekly free pick-up). Oxford is also home to several advertising agencies. Daily Information (known locally as "Daily Info") is an event information and advertising news sheet which has been published since 1964 and now provides a connected website. Nightshift is a monthly local free magazine that has covered the Oxford music scene since 1991.[106]

Culture

[edit]Museums and galleries

[edit]Oxford is home to many museums, galleries, and collections, most of which are free of admission charges and are major tourist attractions. The majority are departments of the University of Oxford. The first of these to be established was the Ashmolean Museum, the world's first university museum,[107] and the oldest museum in the UK.[108] Its first building was erected in 1678–1683 to house a cabinet of curiosities given to the University of Oxford in 1677. The museum reopened in 2009 after a major redevelopment. It holds significant collections of art and archaeology, including works by Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Turner, and Picasso, as well as treasures such as the Scorpion Macehead, the Parian Marble and the Alfred Jewel. It also contains "The Messiah", a pristine Stradivarius violin, regarded by some as one of the finest examples in existence.[109]

The University Museum of Natural History holds the university's zoological, entomological and geological specimens. It is housed in a large neo-Gothic building on Parks Road, in the university's Science Area.[110] Among its collection are the skeletons of a Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops, and the most complete remains of a dodo found anywhere in the world. It also hosts the Simonyi Professorship of the Public Understanding of Science, currently held by Marcus du Sautoy. Adjoining the Museum of Natural History is the Pitt Rivers Museum, founded in 1884, which displays the university's archaeological and anthropological collections, currently holding over 500,000 items. It recently built a new research annexe; its staff have been involved with the teaching of anthropology at Oxford since its foundation, when as part of his donation General Augustus Pitt Rivers stipulated that the university establish a lectureship in anthropology.[111]

The Museum of the History of Science is housed on Broad Street in the world's oldest-surviving purpose-built museum building.[112] It contains 15,000 artefacts, from antiquity to the 20th century, representing almost all aspects of the history of science. In the university's Faculty of Music on St Aldate's is the Bate Collection of Musical Instruments, a collection mostly of instruments from Western classical music, from the medieval period onwards. Christ Church Picture Gallery holds a collection of over 200 old master paintings. The university also has an archive at the Oxford University Press Museum.[113] Other museums and galleries in Oxford include Modern Art Oxford, the Museum of Oxford, the Oxford Castle, Science Oxford and The Story Museum.[114]

Art

[edit]Art galleries in Oxford include the Ashmolean Museum, the Christ Church Picture Gallery, and Modern Art Oxford. William Turner (aka "Turner of Oxford", 1789–1862), was a watercolourist who painted landscapes in the Oxford area. The Oxford Art Society was established in 1891. The later watercolourist and draughtsman Ken Messer (1931–2018) has been dubbed "The Oxford Artist" by some, with his architectural paintings around the city.[115] In 2018, The Oxford Art Book featured many contemporary local artists and their depictions of Oxford scenes.[116] The annual Oxfordshire Artweeks is well-represented by artists in Oxford itself.[117]

Music

[edit]Holywell Music Room is said to be the oldest purpose-built music room in Europe, and hence Britain's first concert hall.[118] Tradition has it that George Frideric Handel performed there, though there is little evidence.[119] Joseph Haydn was awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford University in 1791, an event commemorated by three concerts of his music at the Sheldonian Theatre, directed by the composer and from which his Symphony No. 92 earned the nickname of the "Oxford" Symphony.[120] Victorian composer Sir John Stainer was organist at Magdalen College and later Professor of Music at the university, and is buried in Holywell Cemetery.[121]

Oxford, and its surrounding towns and villages, have produced many successful bands and musicians in the field of popular music. The most notable Oxford act is Radiohead, who all met at nearby Abingdon School, though other well known local bands include Supergrass, Ride, Mr Big, Swervedriver, Lab 4, Talulah Gosh, the Candyskins, Medal, the Egg, Unbelievable Truth, Hurricane No. 1, Crackout, Goldrush and more recently, Young Knives, Foals, Glass Animals, Dive Dive and Stornoway. These and many other bands from over 30 years of the Oxford music scene's history feature in the documentary film Anyone Can Play Guitar?. In 1997, Oxford played host to Radio 1's Sound City, with acts such as Travis, Bentley Rhythm Ace, Embrace, Spiritualized and DJ Shadow playing in various venues around the city including Oxford Brookes University.[122] It is also home to several brass bands, notably the City of Oxford Silver Band, founded in 1887.

Theatres and cinemas

[edit]- Burton Taylor Studio, Gloucester Street

- Curzon Cinema, Westgate, Bonn Square

- Michael Pilch Studio, Jowett Walk

- New Theatre, George Street

- North Wall Arts Centre, South Parade

- Odeon Cinema, George Street

- Odeon Cinema, Magdalen Street

- Old Fire Station Theatre, George Street

- O'Reilly Theatre, Blackhall Road

- Oxford Playhouse, Beaumont Street

- Pegasus Theatre,[123] Magdalen Road

- Phoenix Picturehouse, Walton Street

- Ultimate Picture Palace, Cowley Road

- Vue Cinema, Grenoble Road

- Theatre company

Literature and film

[edit]The city hosts the annual Oxford Literary Festival each Spring. Well-known Oxford-based authors include:

- Brian Aldiss (1925–2017), science fiction novelist, lived in Oxford.[124]

- Vera Brittain (1893–1970), undergraduate at Somerville.

- John Buchan, 1st Baron Tweedsmuir (1875–1940), attended Brasenose College, best known for The Thirty-nine Steps.

- A.S. Byatt (born 1936), Booker Prize winner, undergraduate at Somerville.

- Lewis Carroll (real name Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), (1832–1898), author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, was a student and Mathematical Lecturer of Christ Church.

- Susan Cooper (born 1935), undergraduate at Somerville, best known for her The Dark Is Rising sequence.

- Sir William Davenant (1606–1668), poet and playwright.[125]

- Colin Dexter (1930–2017), wrote and set his Inspector Morse detective novels in Oxford.[124]

- John Donaldson (c. 1921–1989), a poet resident in Oxford in later life.

- Siobhan Dowd (1960–2007), Oxford resident, undergraduate at Lady Margaret Hall.

- Victoria Glendinning (born 1937), undergraduate at Somerville.

- Kenneth Grahame (1859–1932), educated at St Edward's School, wrote The Wind in the Willows.

- Michael Innes (J. I. M. Stewart) (1906–1994), Scottish novelist and academic, Student of Christ Church

- P. D. James (1920–2014), born and died in Oxford; wrote about Adam Dalgliesh

- C. S. Lewis (1898–1963), student at University College and Fellow of Magdalen.

- T. E. Lawrence (1888–1935), "Lawrence of Arabia", Oxford resident, undergraduate at Jesus, postgraduate at Magdalen.

- Iris Murdoch (1919–1999), undergraduate at Somerville and fellow of St Anne's.

- Carola Oman (1897–1978), novelist and biographer, born and brought up in the city.

- Iain Pears (born 1955), undergraduate at Wadham and Oxford resident, wrote An Instance of the Fingerpost.

- Philip Pullman (born 1946), undergraduate at Exeter, teacher and resident in the city.

- Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), undergraduate at Somerville, wrote about Lord Peter Wimsey.

- J. R. R. Tolkien (1892–1973), undergraduate at Exeter and later professor of English at Merton, author of The Lord of the Rings

- John Wain (1925–1994), undergraduate at St John's and later Professor of Poetry at Oxford University 1973–78.

- Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), 19th-century poet and author who attended Oxford from 1874 to 1878.[126]

- Athol Williams (born 1970), South African poet, postgraduate at Hertford and Regent's Park from 2015 to 2020.

- Charles Williams (1886–1945), editor at Oxford University Press.

Oxford appears in the following works:[citation needed]

- the poems The Scholar Gypsy and Thyrsis by Matthew Arnold.[127] Thyrsis includes the lines: "And that sweet city with her dreaming spires, She needs not June for beauty's heightening,..."

- The Scarlet Pimpernel

- "Harry Potter" (all the films to date)

- The Chronicles of the Imaginarium Geographica by James A. Owen

- Jude the Obscure (1895) by Thomas Hardy (in which Oxford is thinly disguised as "Christminster")[128]

- Zuleika Dobson (1911) by Max Beerbohm

- Gaudy Night (1935) by Dorothy L. Sayers

- Brideshead Revisited (1945) by Evelyn Waugh

- A Question of Upbringing (1951 ) by Anthony Powell

- Alice in Wonderland (1951 ) by Walt Disney

- Second Generation (1964) by Raymond Williams

- Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) by Steven Spielberg

- Inspector Morse (1987–2000)

- Where the Rivers Meet (1988) trilogy set in Oxford by John Wain

- All Souls (1989) by Javier Marías

- The Children of Men (1992) by P. D. James

- Doomsday Book (1992) by Connie Willis

- His Dark Materials trilogy (1995 onwards) by Philip Pullman

- Tomorrow Never Dies (1997)[129]

- The Saint (1997)

- 102 Dalmatians (2000)

- Endymion Spring (2006) by Matthew Skelton

- Lewis (2006–15)

- The Oxford Murders (2008)

- Mr. Nice (1996), autobiography of Howard Marks, subsequently a 2010 film

- A Discovery of Witches (2011) by Deborah Harkness

- X-Men: First Class (2011)

- Endeavour (2012 onwards)

- The Reluctant Cannibals (2013) by Ian Flitcroft

- Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again (2018)

- The Late Scholar by Jill Paton Walsh, part of the continuation of the Lord Peter Wimsey books of Dorothy L. Sayers

Sport

[edit]|

This section

needs additional citations for verification.

(October 2022)

|

Football

[edit]

The city's leading football club, Oxford United, compete in the EFL Championship, the second level of the English football league system, following promotion in the 2023–24 season. They play at the Kassam Stadium (named after former chairman Firoz Kassam), which is near the Blackbird Leys housing estate and has been their home since relocation from the Manor Ground in 2001.

Oxford City F.C. is a semi-professional football club, separate from Oxford United, they play in the National League North, the sixth tier, two levels below the Football League in the pyramid.

Oxford City Nomads F.C. was a semi-professional football club that ground-shared with Oxford City and played in the Hellenic league.

Rowing

[edit]Oxford University Boat Club compete in the world-famous Boat Race. Since 2007 the club has been based at a training facility and boathouse in Wallingford,[130] south of Oxford, after the original boathouse burnt down in 1999. Oxford Brookes University also has an elite rowing club,[131] and there are public clubs near Donnington Bridge, namely the City of Oxford Rowing Club,[132] Falcon Boat Club[133] and Oxford Academicals Rowing Club.[134]

Cricket

[edit]Oxford University Cricket Club is Oxford's most famous club with more than 300 Oxford players gaining international honours, including Colin Cowdrey, Douglas Jardine and Imran Khan.[135] Oxfordshire County Cricket Club play in the Minor Counties League.

Athletics

[edit]Headington Road Runners are based at the OXSRAD sports facility in Marsh Lane (next to Oxford City F.C.) is Oxford's only road running club with an average annual membership exceeding 300. It was the club at which double Olympian Mara Yamauchi started her running career.

Rugby league

[edit]In 2013, Oxford Rugby League entered rugby league's semi-professional Championship 1, the third tier of British rugby league. Oxford Cavaliers, who were formed in 1996, compete at the next level, the Conference League South. Oxford University (The Blues)[136] and Oxford Brookes University (The Bulls)[137] both compete in the rugby league BUCS university League.

Rugby union

[edit]Oxford Harlequins RFC is the city's main Rugby Union team and currently plays in the South West Division. Oxford R.F.C is the oldest city team and currently plays in the Berks, Bucks and Oxon Championship. Their most famous player was arguably Michael James Parsons known as Jim Parsons who was capped by England.[138] Oxford University RFC are the most famous club with more than 300 Oxford players gaining International honours; including Phil de Glanville, Joe Roff, Tyrone Howe, Anton Oliver, Simon Halliday, David Kirk and Rob Egerton.[139] London Welsh RFC moved to the Kassam Stadium in 2012 to fulfil their Premiership entry criteria regarding stadium capacity. At the end of the 2015 season, following relegation, the club left Oxford.[140]

Hockey

[edit]There are several field hockey clubs based in Oxford. The Oxford Hockey Club (formed after a merger of City of Oxford HC and Rover Oxford HC in 2011) plays most of its home games on the pitch at Oxford Brookes University, Headington Campus and also uses the pitches at Headington Girls' School and Iffley Road. Oxford Hawks has two astroturf pitches at Banbury Road North, by Cutteslowe Park to the north of the city.

Ice hockey

[edit]Oxford City Stars is the local Ice Hockey Team which plays at Oxford Ice Rink. There is a senior/adults' team[141] and a junior/children's team.[142] The Oxford University Ice Hockey Club was formed as an official University sports club in 1921, and traces its history back to a match played against Cambridge in St Moritz, Switzerland in 1885.[143] The club currently competes in Checking Division 1 of the British Universities Ice Hockey Association.[144]

Speedway and greyhound racing

[edit]

Oxford Cheetahs motorcycle speedway team has raced at Oxford Stadium in Cowley on and off since 1939. The Cheetahs competed in the Elite League and then the Conference League until 2007. They were Britain's most successful club in the late 1980s, becoming British League champions in 1985, 1986 and 1989. Four-times world champion Hans Nielsen was the club's most successful rider. Greyhound racing took place at the Oxford Stadium from 1939 until 2012 and hosted some of the sport's leading events such as the Pall Mall Stakes, The Cesarewitch and Trafalgar Cup. The stadium remains intact but unused after closing in 2012.

American football

[edit]Oxford Saints is Oxford's senior American Football team. One of the longest-running American football clubs in the UK, the Saints were founded in 1983 and have competed for over 40 years against other British teams across the country.

Gaelic football

[edit]Éire Óg Oxford is Oxford's local Gaelic Football team. Originally founded as a hurling club by Irish immigrants in 1959,[145] the club plays within the Hertfordshire league and championship,[146] being the only Gaelic Football club within Oxfordshire. Hurling is no longer played by the club; however, Éire Óg do contribute players to the Hertfordshire-wide amalgamated club, St Declans. Several well-known Irishmen have played for Éire Óg, including Darragh Ennis of ITV's The Chase, and Stephen Molumphy, former member of the Waterford county hurling team.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]

Notable religious buildings include: Oxford Central Mosque, Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, the Seat of the Bishop of Oxford, University Church of St Mary the Virgin, the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, and the Oxford Oratory. The city was also the birthplace of the Oxford Movement and the Wesleyan Church.

International relations

[edit]- Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany[148]

- Grenoble, Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes, France[149]

- Leiden, South Holland, Netherlands

- Manizales, Caldas Department, Colombia[150]

- León, León Department, Nicaragua

- Perm, Perm Krai, Russia (suspended in 2022 after the Russian invasion of Ukraine)[151][152]

- Ramallah, West Bank, Palestine[153]

- Wrocław, Lower Silesia, Poland

- Padua, Veneto, Italy[154]

Freedom of the City

[edit]The following people and military units have received the Freedom of the City of Oxford.

Individuals

[edit]- Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson: 22 July 1802.

- Arthur Annesley, 11th Viscount Valentia: 6 December 1900.

- Admiral of the Fleet Sir Reginald Tyrwhitt: 3 February 1919.

- Admiral of the Fleet Lord Beatty: 25 June 1919.

- Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig: 25 June 1919.

- Sir Michael Sadler: 18 May 1931.

- Benjamin R. Jones: 4 September 1942.

- William Morris, 1st Viscount Nuffield: 15 January 1951.

- Sir Robert Menzies: 6 June 1953.

- Alic Halford Smith: 10 February 1955.

- Vivian Smith, 1st Baron Bicester: 1 March 1955.

- Clement Attlee: 16 January 1956.

- Sir Basil Blackwell: 12 January 1970.

- Olive Gibbs: 17 June 1982.

- Nelson Mandela: 23 June 1997.

- Aung San Suu Kyi: 15 December 1997 (Revoked by Oxford City Council on 27 November 2017).

- Colin Dexter: 26 February 2001.

- Professor Sir Richard Doll: 16 September 2002.

- Sir Roger Bannister: 12 May 2004.

- Sir Philip Pullman: 24 January 2007.

- Professor Christopher Brown: 2 July 2014.

- Benny Wenda: 17 July 2019.[155]

Military units

[edit]- Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry: 1 October 1945.

- 1st Green Jackets (43rd and 52nd): 7 November 1958.

- Royal Green Jackets: 1 January 1966.

- The Rifles: 1 February 2007.[157]

See also

[edit]- Bishop of Oxford

- Earl of Oxford

- List of attractions in Oxford

- List of Oxford architects

- Mayors of Oxford

- Oxfam

- Oxford bags

- The Oxfordian Age – a subdivision of the Jurassic Period named for Oxford

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Councillors". Oxford City Council. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ a b UK Census (2021). "2021 Census Area Profile – Oxford Local Authority (E07000178)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Upton, Clive; et al., eds. (2001). The Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 734. ISBN 978-0-19-863156-9.

- ^ Dictionary.com, "oxford" in Dictionary.com Unabridged. Source location: Random House, Inc. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/oxford Archived 23 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Available: http://dictionary.reference.com Archived 20 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed: 4 July 2012.

- ^ Sager 2005, p. 36.

- ^ a b "The History of Oxford, City of Dreaming Spires". Historic UK. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ "A brief history of the University". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ Crouch, D. (2013). The Reign of King Stephen: 1135–1154 (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-31789-297-7.

- ^ Abrams, Rebecca (2022). Licoricia of Winchester: Power and Prejudice in Medieval England (1st ed.). Winchester: The Licoricia of Winchester Appeal. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-1-3999-1638-7.

- ^ "History | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W. N. (1973). Oxford in the Age of John Locke. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-8061-1038-7.

- ^ "Daily Data from the Radcliffe Observatory site in Oxford". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Radcliffe Meteorological Station". Archived from the original on 1 June 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ^ "Monthly, Annual and Seasonal Data from the Radcliffe Observatory site in Oxford". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Oxford (Oxfordshire) UK climate averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 25 April 2023. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Daily Data from the Radcliffe Observatory site in Oxford". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "About Boswells". Boswells-online.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ Ffrench, Andrew (29 February 2020). "Everything must go now at Boswells in closing down sale". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 29 March 2020. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ^ "The Oxford Green Belt: Key Facts". CPRE Oxfordshire. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ Ffrench, Andy (4 March 2017). "Estate agents call for building on Green Belt to ease house price crisis". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Elledge, Jonn (22 September 2017). "Loosen Britain's green belt. It is stunting our young people". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ White, Anna (26 February 2015). "Welcome to Britain's most unaffordable spot – it's not London". Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2019 – via The Telegraph.

- ^ "Oxford Green Belt Study Final Report Prepared by LUC" (PDF). Oxfordshire County Council. October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Local Government Act 1972", legislation.gov.uk, The National Archives, 1972 c. 70, retrieved 25 April 2023

- ^ Historic England. "Town Hall, Municipal Buildings and Library (Grade II*) (1047153)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Parish council contact details". Oxford City Council. Archived from the original on 25 May 2023. Retrieved 25 April 2023.

- ^ "Economic Profile of Oxford". Oxford City Council. Archived from the original on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ "Elsevier". The Publishers Association. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Home – Digital Oxford". Digital Oxford. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Passle – become a thought leader". Passle: Don't have time to blog?. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Brainomix". Brainomix. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ "Labstep". angel.co. Archived from the original on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Learn English in Oxford". Oxford Royale. oxford-royale.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ Hearn, Dan (19 August 2009). "Oxford tourism suffers triple whammy". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ "Clarendon Shopping Centre". Clarendoncentre.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Visit Oxford's premier shopping centre – the Westgate Shopping Centre". Oxfordcity.co.uk. 18 May 2009. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Blackwell's Books, Oxford". britainexpress.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ^ a b c d Woolley, Liz (2010). "Industrial Architecture in Oxford, 1870 to 1914". Oxoniensia. LXXV. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society: 78. ISSN 0308-5562.

- ^ Page, William, ed. (1907). A History of the County of Oxford, Volume 2: Industries: Malting and Brewing. Victoria County History. Archibald Constable & Co. pp. 225–277. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ^ Richmond, Lesley; Turton, Alison (1990). The Brewing industry: a guide to historical records. Manchester University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-7190-3032-1. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ "History of Headington, Oxford". Headington.org.uk. 19 April 2009. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Morrells Brewery up for sale". Archive.thisisoxfordshire.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ www.quaffale.org.uk (22 September 2001). "Morrells Brewery Ltd". Quaffale.org.uk. Archived from the original on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Jericho Echo". Pstalker.com. Archived from the original on 8 August 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Brewer buys pub chain for £67m". BBC News. 18 June 2002. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ "Brewery site plan nears final hurdle". Archive.thisisoxfordshire.co.uk. 19 February 2001. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ^ Evans, Marc (27 July 2017). "Grab a glass: The Oxford Artisan Distillery opens in South Park today". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 10 September 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^ "Bell Founders". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ^ a b c Council, Oxford City. "Oxford's population statistics". Oxford City Council. Retrieved 1 March 2025.

- ^ Equality, Commission for Racial (1985). "Ethnic minorities in Britain: statistical information on the pattern of settlement". Commission for Racial Equality: Table 2.2. Archived from the original on 13 May 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Data is taken from United Kingdom Casweb Data services Archived 15 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine of the United Kingdom 1991 Census on Ethnic Data for England, Scotland and Wales Archived 5 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine (Table 6)

- ^ "Office of National Statistics; 2001 Census Key Statistics". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2 June 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "2011 Census: Ethnic Group, local authorities in England and Wales". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ "Ethnic group, census2021 (TS021)". webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2022.

- ^ "KS007 - Religion". Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "2011 census – theme tables". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Religion - Office for National Statistics". Archived from the original on 29 November 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Hikins, Richard (4 March 2016). "New Global Headquarters for Airways Aviation". oxfordairport.co.uk. Oxford Airport. Archived from the original on 28 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Airbus Helicopters celebrates 40 years as the all-in-one solution for UK helicopter industry". Helicopters. Airbus. 15 July 2014. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Park and ride car parks". Roads and transport. Oxfordshire County Council. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Oxford Bus Company Fleet List" (PDF). Oxford Bus Company. August 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ Little, Reg (15 July 2010). "Transport revolution". The Oxford Times. Oxford: Newsquest (Oxfordshire) Ltd. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ Holley, Mel (10 September 2014). "Gyrodrive debuts in Oxford". RouteOne. Diversified Communications. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ^ "Smart ticketing". Sustainability. Go-Ahead Group. Archived from the original on 6 February 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Free Wi-Fi on city buses and buildings as Oxford gets Super Connected". Newsroom. Oxford City Council. 13 October 2014. Archived from the original on 21 April 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Oxford Bus Company (4 November 2014). "Free Wi-Fi on buses announced as Oxford gets Super Connected!". WordPress. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015.

- ^ "Oxford bus users to get free wifi". News. ITV. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015.

- ^ "2011 Census Analysis – Cycling to Work". ONS. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 25 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ MacDermot 1927, pp. 180–181.

- ^ a b MacDermot 1927, p. 300.

- ^ a b MacDermot 1927, p. 327.

- ^ Mitchell & Smith 2005, Historical Background.

- ^ Mitchell & Smith 2005, fig. 8.

- ^ "Welcome to". East West Rail. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Western Section". East West Rail. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Central Section". East West Rail. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Eastern Section". East West Rail. 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ Simpson 1997, p. 59.

- ^ Simpson 2001, p. 9.

- ^ Simpson 1997, p. 101.

- ^ Simpson 2001, p. 57.

- ^ a b MacDermot 1931, p. 432.

- ^ Cooke 1960, p. 70.

- ^ MacDermot 1927, p. 498.

- ^ MacDermot 1927, p. 551.

- ^ MacDermot 1931, p. 27.

- ^ Thacker, Fred. S. (1968) [1920]. The Thames Highway: Volume II Locks and Weirs. Newton Abbot: David and Charles.

- ^ Compton, Hugh J. (1976). The Oxford Canal. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-7238-8.

- ^ "About Oxford's Zero Emission Zone". Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Bus lanes and bus gates". Oxfordshire County Council. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Colivicchi, Anna. "Plans for six traffic filters in Oxford approved by council". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "Consultation on trial traffic filters 2022". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Oxford University and Oxford Bus Company back traffic filters". BBC News. 4 November 2022. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Ffrench, Andrew (25 October 2022). "Opinion: Why six new bus gates will be a mistake for Oxford says top hotelier". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ Ffrench, Andrew (25 November 2022). "Legal challenge to bus gates is 'last resort' says Jeremy Mogford". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Introduction and history". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "International students". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2016–2017". Times Higher Education. September 2016. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "Libraries". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012.

- ^ "A University Library for the Twenty-first Century". University of Oxford. 22 September 2005. Archived from the original on 2 September 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ "Oxford Student Radio". oxideradio.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ "Milestone Group" (PDF). Milestone Group. Retrieved 17 April 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Ffrench, Andrew (7 April 2015). "New Oxfordshire community TV channel 'just weeks from launch'". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "Preview: Nightshift night Archived 5 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine", "Oxford Mail", 6 July 2000

- ^ MacGregor, A. (2001). The Ashmolean Museum: A brief history of the museum and its collections. Ashmolean Museum/Jonathan Horne Publications.

- ^ "Support Us". The Ashmolean. Archived from the original on 3 May 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ "Ashmolean Museum website, What's in the Ashmolean". Oxford University Ashmolean Museum. Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "Oxford University Museum of Natural History Homepage". Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 27 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- ^ "Pitt Rivers Museum Website, About Augustus Pitt Rivers". University of Oxford Pitt Rivers Museum. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ "About the Museum". Museum of the History of Science. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 9 October 2007.

- ^ "Visiting museums, libraries & places of interest – University of Oxford website". Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Museums and Galleries – Experience Oxfordshire website". Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ "Obituary: Oxford artist Ken Messer". Oxford Mail. UK. 7 June 2018. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Bennett, Emma, ed. (2018). The Oxford Art Book: The City Through the Eyes of its Artists. UIT Cambridge. ISBN 978-1-906-860-84-4.

- ^ "Oxford". Artweeks 2020. Oxfordshire Artweeks. 2020. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Tyack, Geoffrey (1998). Oxford: An architectural guide. Oxford University Press. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-14-071045-8.

- ^ "Exploring Wadham's Holywell Music Room". Wadham College. 21 February 2017. Archived from the original on 13 January 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Haydn in England". Oxford University Department for Continuing Education. 2018. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Notable people buried in Oxford". Oxford City Council. Archived from the original on 1 December 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Discography for NME Compilation Cassette for Oxford Sound City". Discogs. 1997. Archived from the original on 29 July 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Pegasus Theatre". pegasustheatre.org.uk. UK. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2013., UK.

- ^ a b "Oxford authors Colin Dexter and Brian Aldiss added to biography dictionary". 14 January 2021.

- ^ Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). pp. 851–852.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). pp. 632–633.

- ^ "Poems". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Gray, John (n.d.). "'Only a thickness of wall': Empire and Oxford in Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure (1895)". Oxford and Empire Network. University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2023.

- ^ Della Sala, Sofia (28 September 2021). "James Bond: Every Oxfordshire filming location in No Time To Die, Spectre and more". Oxfordshire Live. Archived from the original on 22 June 2023. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Contact Us". Oxford University Boat Club. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ^ "Oxford Brookes University opens elite rowing facilities". BBC News. 4 June 2013. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "About Us". City of Oxford Rowing Club. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "About Falcon". Falcon Boat Club. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "Find Us". Oxford Academicals Rowing Club. Archived from the original on 7 March 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "International Players". Oxford University Cricket in the Parks. Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "Welcome to OURLFC". Oxford University Rugby League. Archived from the original on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ^ "Oxford Brookes University Rugby League". Facebook. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ "Rugby Union". ESPN. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "International Players". Oxford University Rugby Club. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ Knox, Michael (27 June 2015). "RUGBY UNION: London Welsh quit Oxford's Kassam Stadium – but could be back". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 12 March 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "oxfordstars.com". Archived from the original on 10 October 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ "oxfordjuniorstars.co.uk". oxfordstars.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 April 2011.

- ^ "OUIHC". oxforduniversityicehockey.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "OUIHC BUIHA". buiha.org.uk. Archived from the original on 14 February 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "Éire Óg Oxford: Sixty Years" (online booklet). Éire Óg Oxford. 2019. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "About Us". Eire Óg Oxford. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "Oxford's International Twin Towns". Oxford City Council. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ^ "City Twinnings". Stadt Bonn. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- ^ Jérôme Steffenino, Marguerite Masson. "Ville de Grenoble – Coopérations et villes jumelles". Grenoble.fr. Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ^ Bragg, Alexander (21 October 2016). "The Oxford – Manizales connection of "town versus gown"". The City Paper. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Tim (4 March 2022). "Oxford City Council ends unpopular Perm twin link in U-turn". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 6 March 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ "Оксфорд разорвал отношения с Пермью из-за спецоперации на Украине". Ura.news. 5 March 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2022.

- ^ Council, Oxford City. "Historic moment as Oxford and Ramallah in Palestine become twin cities". www.oxford.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ "Oxford, Padua, Ramallah – twin cities recognised". Oxford City Council. 4 November 2019. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Benny Wenda: West Papua leader receives freedom of Oxford". BBC News. 17 July 2019. Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Freedom of the City". Archived from the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- ^ Ffrench, Andrew (21 May 2015). "Regiment to exercise 'Freedom of the City'". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Cooke, B.W.C., ed. (January 1960). "The Why and the Wherefore: Distances from London to Oxford". The Railway Magazine. Vol. 106, no. 705. Westminster: Tothill Press.

- MacDermot, E.T. (1927). History of the Great Western Railway, vol. I: 1833–1863. Paddington: Great Western Railway.

- MacDermot, E.T. (1931). History of the Great Western Railway, vol. II: 1863–1921. Paddington: Great Western Railway.

- Mitchell, Vic; Smith, Keith (July 2005). Oxford to Bletchley. Country Railway Routes. Middleton Press. ISBN 1-904474-57-8.

- Sager, Peter (2005). Oxford & Cambridge: An Uncommon History. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-51249-3.

- Saint, Andrew (1970). "Three Oxford Architects". Oxoniensia. XXXV. Oxfordshire Architectural and Historical Society. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Simpson, Bill (1997). A History of the Railways of Oxfordshire. Vol. Part 1: The North. Banbury and Witney: Lamplight. ISBN 1-899246-02-9.

- Simpson, Bill (2001). A History of the Railways of Oxfordshire. Vol. Part 2: The South. Banbury and Witney: Lamplight. ISBN 1-899246-06-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Aston, Michael; Bond, James (1976). The Landscape of Towns. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-460-04194-0.

- Attlee, James (2007). Isolarion: A Different Oxford Journey. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-03093-7.

- Curl, James Stevens (1977). The Erosion of Oxford. Oxford Illustrated Press Ltd. ISBN 0-902280-40-6.

- Dale, Lawrence (1944). Towards a Plan for Oxford City. London: Faber and Faber.

- Gordon, Anne (22 June 2008). "History, learning, beauty reign over Oxford". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- Morris, Jan (2001). Oxford. Oxford: Oxford Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-19-280136-4.

- Sharp, Thomas (1948). Oxford Replanned. London: The Architectural Press.

- Tyack, Geoffrey (1998). Oxford An Architectural Guide. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-817423-3.

- Woolley, A. R. (1975). The Clarendon Guide to Oxford (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-951047-4.

External links

[edit]- Howarth, Osbert John Radcliffe (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). pp. 405–414.

- Oxford

- Cities in South East England

- County towns in England

- Local authorities adjoining the River Thames

- Local government in Oxfordshire

- Populated places established in the 8th century

- Tourism in Oxford

- Non-metropolitan districts of Oxfordshire

- 8th-century establishments in England

- Towns in Oxfordshire

- Oxfordian (stage)

- Boroughs in England

- Former civil parishes in Oxfordshire