Philadelphia

|

Philadelphia

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Etymology:Ancient Greek:φίλοςphílos(beloved, dear) andἀδελφόςadelphós(brother, brotherly) ———-——— |

|

| Nickname(s):

"Philly", "The City of Brotherly Love",

others

|

|

| Motto: | |

Interactive map outlining Philadelphia

|

|

|

Location within the

state of Pennsylvania

Location within the

United States

Location in

North America

Location on

Earth

|

|

| Coordinates:39°57′10″N75°09′49″W / 39.9528°N 75.1636°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Philadelphia |

| Historic countries | Kingdom of England Kingdom of Great Britain |

| Historic colony | Province of Pennsylvania |

| Founded | 1682[3] |

| Incorporated | October 25, 1701 |

| Founded by | William Penn |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council,consolidated city-county |

| • Body | Philadelphia City Council |

| •Mayor | Cherelle Parker(D) |

| Area | |

| •Consolidated city-county | 142.70 sq mi (369.59 km2) |

| • Land | 134.36 sq mi (347.98 km2) |

| • Water | 8.34 sq mi (21.61 km2) |

| Elevation | 39 ft (12 m) |

| Population | |

| •Consolidated city-county | 1,603,797 |

| • Estimate

(2022)

[6]

|

1,567,258 |

| • Rank | 10thin North America 6thin the United States 1stin Pennsylvania |

| • Density | 11,936.92/sq mi (4,608.86/km2) |

| •Urban | 5,696,125 (US:7th) |

| • Urban density | 3,000.8/sq mi (1,158.6/km2) |

| •Metro | 6,245,051 (US:7th) |

| Demonym | Philadelphian |

| GDP | |

| • Philadelphia (MSA) | $518.5 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5(EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4(EDT) |

| ZIP Codes |

19092–19093, 19099, 191xx

|

| Area codes | 215, 267, 445 |

| FIPS code | 42-60000 |

| GNISfeature ID | 1215531[10] |

| Website | www.phila.gov |

Philadelphia, colloquially referred to asPhilly, is themost populous cityin theU.S. stateofPennsylvania[11]and thesixth-most populous city in the nation, with a population of 1,603,797 in the2020 census. The city is the urban core of the largerDelaware Valley, also known as the Philadelphia metropolitan area, thenation's seventh-largestand one of theworld's largestmetropolitan regionswith 6.245 million residents in itsmetropolitan statistical areaand 7.366 million residents in itscombined statistical area.[12]

Philadelphia is known forits extensive contributionstoUnited States history. The city served asthe nation's capitaluntil 1800.[13]It maintains contemporary influence inbusiness and industry,culture,sports, andmusic.[14][15]Philadelphia was founded in 1682 byWilliam Penn, anEnglishQuakerand advocate ofreligious freedom. The city served as the capital of thePennsylvania Colonyduring theBritish colonial era[3][16]and went on to play a historic and vital role as the central meeting place for thenation's founding fathers. Philadelphia hosted theFirst Continental Congressin 1774, preserved theLiberty Bell, and hosted theSecond Continental Congressduring which the founders signed theDeclaration of Independence.[17]TheU.S. Constitutionwas later ratified in Philadelphia at thePhiladelphia Conventionof 1787. Philadelphia remained the nation's largest city until 1790, served as the nation's first capital from May 10, 1775, until December 12, 1776, and on four subsequent occasions during and following theAmerican Revolutionary War, including from 1790 to 1800 during the construction of the new national capital ofWashington, D.C.

With18 four-year universities and colleges, Philadelphia is one of the nation's leading centers for higher education andacademic research.[18][19]As of 2022[update], the Philadelphia metropolitan area had agross metropolitan productof US$518.5 billion.[9]The city is home to fiveFortune 500corporate headquarters as of 2022.[20]As of 2024, metropolitan Philadelphia ranks as one of the Big Five U.S.venture capitalhubs, facilitated by its proximity to both theentrepreneurialandfinancial ecosystemsofNew York Cityand to thefederal regulatory environmentof Washington, D.C.[21]ThePhiladelphia Stock Exchange, owned byNasdaqsince 2008, is the nation's oldest stock exchange and a global leader inoptionstrading.[22]30th Street Station, the city's primary rail station, is thethird-busiest Amtrak hubin the nation, and the city'smultimodal transportandlogisticsinfrastructure also includesPhiladelphia International Airport, a majorTransatlanticgateway and hub,[23]and the rapidly-growingPhilaPort seaport.[24]

Philadelphia is a national cultural center, hosting moreoutdoor sculpturesand murals than any other city in the nation.[25][26]Fairmount Park, when combined with adjacentWissahickon Valley Parkin the samewatershed, is 2,052 acres (830 ha), representing one of the nation's largest and theworld's 45th-largesturban park.[27]The city is known for its arts,culture,cuisine, andcolonialandRevolution-erahistory; in 2016, it attracted 42 million domestic tourists who spent $6.8 billion, representing $11 billion in economic impact to the city and its surrounding Pennsylvania counties.[28]Withfive professional sports teamsand one of the nation's most loyal fan bases, Philadelphia is often ranked as the nation's best city for professional sports fans.[29][30][31][32]The city has a culturally andphilanthropicallyactiveLGBTQ+ community. Philadelphia also has played an immensely influential historic and ongoing role in the development and evolution of American music, especiallyR&B,soul, androck.[33][34]

Philadelphia is a city of many firsts, including the nation's firstlibrary(1731),[35]hospital(1751),[35]medical school(1765),[36]national capital(1774),[37]university (by some accounts)(1779),[38]central bank(1781),[39]stock exchange(1790),[35]zoo(1874),[40]andbusiness school(1881).[41]Philadelphia contains 67National Historic Landmarks, includingIndependence Hall.[42][43][19]From the city's 17th century founding through the present, Philadelphia has been the birthplace or home to an extensive number ofprominent and influential Americans. In 2021,Timemagazine named Philadelphia one of the world's greatest 100 places.[44]Two years later, in 2023, travel guide publisherLonely Planetranked Philadelphia the best city in the nation to visit.[45]

History

Native peoples

Prior to the arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century, the Philadelphia area was home to theLenape (Delaware)Indiansin the village ofShackamaxon. They were also called the Delaware Indians,[46]and their historical territory was along theDelaware Riverwatershed, westernLong Island, and theLower Hudson Valley.[a]Most Lenape were pushed out of their Delaware homeland during the 18th century by expanding European colonies, exacerbated by losses from intertribal conflicts.[46]Lenape communities were weakened by newly introduced diseases, mainlysmallpox, and conflict with Europeans. TheIroquoisoccasionally fought the Lenape. Surviving Lenape moved west into the upperOhio Riverbasin. TheAmerican Revolutionary Warand the United States' independence pushed them further west. In the 1860s, the United States government sent most Lenape remaining in theeastern United Statesto theIndian Territoryto present-dayOklahomaand surrounding territories under theIndian removalpolicy.

Colonial

Europeans came to theDelaware Valleyin the early 17th century. The first settlements were founded byDutch colonists, who builtFort Nassauon theDelaware Riverin 1623 in what is nowBrooklawn, New Jersey. The Dutch considered the entire Delaware River valley to be part of theirNew Netherlandcolony. In 1638, Swedish settlers led by renegade Dutch established the colony ofNew SwedenatFort Christina, located in present-dayWilmington, Delaware, and quickly spread out in the valley. In 1644, New Sweden supported theSusquehannocksin their war againstMarylandcolonists.[47]In 1648, the Dutch builtFort Beversreedeon the west bank of the Delaware, south of theSchuylkill Rivernear the present-dayEastwicksection of Philadelphia, to reassert their dominion over the area. TheSwedesresponded by buildingFort Nya Korsholm, or NewKorsholm, named after a town inFinlandwith a Swedish majority.

In 1655, aDutch militarycampaign led by New Netherland Director-GeneralPeter Stuyvesanttook control of the Swedish colony, ending its claim to independence. The Swedish andFinnish peoplesettlers continued to have their ownmilitia, religion, and court, and to enjoy substantial autonomy under the Dutch. An English fleet captured the New Netherland colony in 1664, though the situation did not change substantially until 1682, when the area was included inWilliam Penn's charter for Pennsylvania.[48]

In 1681, in partial repayment of a debt,Charles II of Englandgranted Penn acharterfor what would become thePennsylvania colony. Despite the royal charter, Penn bought the land from the localLenapein an effort to establish good terms with the Native Americans and ensure peace for the colony.[49]Penn made atreaty of friendshipwith Lenape chiefTammanyunder an elm tree atShackamaxon, in what is now the city'sFishtownneighborhood.[3]Penn named the city Philadelphia, which isGreekfor "brotherly love", derived from theAncient Greektermsφίλοςphílos(beloved, dear) andἀδελφόςadelphós(brother, brotherly). There were a number of cities namedPhiladelphiain theEastern Mediterraneanduring the Greek and Roman periods, including modernAlaşehir, mentioned as the site of an early Christian congregation in theBook of Revelation. As aQuaker, Penn had experiencedreligious persecutionand wanted his colony to be a place where anyone could worship freely. This tolerance, which exceeded that of other colonies, led to better relations with the local native tribes and fostered Philadelphia's rapid growth into America's most important city.[50]

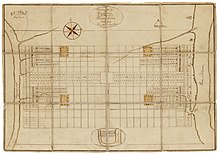

Penn planned a city on the Delaware River to serve as a port and place for government. Hoping that Philadelphia would become more like an English rural town instead of a city, Penn laid out roads on agrid planto keep houses and businesses spread far apart with areas for gardens andorchards.

The city's inhabitants did not follow Penn's plans, however, and instead crowded the present-dayPort of Philadelphiaon the Delaware River and subdivided and resold their lots.[51]Before Penn left Philadelphia for the final time, he issued the Charter of 1701 establishing it as a city. Though poor at first, Philadelphia became an important trading center with tolerable living conditions by the 1750s.Benjamin Franklin, a leading citizen, helped improve city services and founded new ones that were among the first in the nation, including afire company,library, andhospital.

A number ofphilosophical societieswere formed, which were centers of the city's intellectual life, including the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture (1785), the Pennsylvania Society for the Encouragement of Manufactures and the Useful Arts (1787), theAcademy of Natural Sciences(1812), and theFranklin Institute(1824).[52]These societies developed and financed new industries that attracted skilled and knowledgeable immigrants from Europe.

American Revolution

Philadelphia's importance and central location in the colonies made it a natural center forAmerica's revolutionaries. By the 1750s, Philadelphia surpassedBostonas the largest city and busiestportinBritish America, and the second-largest city in the entireBritish EmpireafterLondon.[54][55]In 1774, as resentment ofBritish colonialpractices and support for independence was burgeoning in the colonies, Philadelphia hosted theFirst Continental Congress.

From 1775 to 1781, Philadelphia hosted theSecond Continental Congress,[56]which adopted theDeclaration of Independencein what was then called thePennsylvania State Houseand was later renamed Independence Hall. HistorianJoseph Ellis, in 2007, described the Declaration of Independence, written predominantly byThomas Jefferson, as "the most potent and consequential words in American history,"[17]and its adoption represented a declaration of war against theBritish Army, which was then the world's most powerful military force. Since the Declaration's July 4, 1776, adoption, its signing has been cited globally and repeatedly by various peoples of the world seeking independence and liberty. It also has been, since its adoption, the basis for annual celebration by Americans; in 1938, this celebration of the Declaration was formalized asIndependence Day, one of onlyten designated U.S. federal holidays.

AfterGeorge Washington's defeat at theBattle of BrandywineinChadds Ford Township, on September 11, 1777, during thePhiladelphia campaign, the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia was defenseless and the city prepared for what was perceived to be an inevitable British attack. Because bells could easily be recast into munitions, theLiberty Bell, then known as the Pennsylvania State Bell, and bells from two Philadelphia churches,Christ ChurchandSt. Peter's Church, were hastily taken down and transported by heavily guarded wagon train out of the city. The Liberty Bell was taken toZion German Reformed Churchin Northampton Town, which is present-dayAllentown, where it was hidden under the church's floor boards for nine months from September 1777 until the British Army's departure from Philadelphia in June 1778.[57]Two Revolutionary War battles, theSiege of Fort Mifflin, fought between September 26 and November 16, 1777, and theBattle of Germantown, fought on October 4, 1777, took place within Philadelphia's city limits.

In Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress adopted theArticles of Confederationon November 15, 1777, and the city later served as the meeting place for theConstitutional Convention, which ratified theConstitutionin Independence Hall in Philadelphia on September 17, 1787.

Philadelphia served as capital of the United States for much of the colonial and early post-colonial periods, including for a decade, from 1790 to 1800, whileWashington, D.C., was being constructed and prepared to serve as the new national capital.[58]In 1793, the largestyellow fever epidemicin U.S. history killed approximately 4,000 to 5,000 people in Philadelphia, or about ten percent of the city's population at the time.[59][60]The capital of the United States was moved to Washington, D.C. in 1800 upon completion of theWhite HouseandU.S. Capitolbuildings.

The state capital was moved from Philadelphia toLancasterin 1799, then ultimately toHarrisburgin 1812. Philadelphia remained the nation's largest city until the late 18th century. It also was the nation's financial and cultural center until ultimately being eclipsed in total population byNew York Cityin 1790. In 1816, the city's free Black community founded theAfrican Methodist Episcopal Church, the first independent Black denomination in the country, and the first BlackEpiscopal Church. The free Black community also established many schools for its children with the help ofQuakers. Large-scale construction projects for new roads,canals, and railroads made Philadelphia the first majorindustrialcity in the United States.

19th century

Throughout the 19th century, Philadelphia hosted a variety of industries and businesses; the largest was thetextile industry. Major corporations in the 19th and early 20th centuries included theBaldwin Locomotive Works,William Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding Company, and thePennsylvania Railroad.[61]Established in 1870, the Philadelphia Conveyancers' Association was chartered by the state in 1871. Along with the U.S. Centennial in 1876, the city's industry was celebrated in theCentennial Exposition, the first officialWorld's fairin the U.S.

Immigrants, mostly from Ireland and Germany, settled in Philadelphia and the surrounding districts. These immigrants were largely responsible for thefirst general strike in North Americain 1835, in which workers in the city won the ten-hour workday. The city was a destination for thousands of Irish immigrants fleeing theGreat Faminein the 1840s; housing for them was developed south ofSouth Streetand later occupied by succeeding immigrants. They established a network ofCatholicchurches and schools and dominated the Catholic clergy for decades. Anti-Irish, anti-Catholicnativistriotserupted in Philadelphia in 1844. The rise in population of the surrounding districts helped lead to theAct of Consolidation of 1854, which extended the city limits from the 2 square miles (5.2 km2) ofCenter Cityto the roughly 134 square miles (350 km2) ofPhiladelphia County.[62][63]In the latter half of the 19th century and leading into the 20th century, immigrants from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Italy, and African Americans from thesouthern U.S.settled in the city.[64]

Philadelphia was represented by theWashington Graysin theAmerican Civil War. The African-American population of Philadelphia increased from 31,699 to 219,559 between 1880 and 1930, largely stemming from theGreat Migrationfrom theSouth.[65][66]

20th century

By the 20th century, Philadelphia had an entrenchedRepublicanpolitical machineand a complacent population.[67]In 1910,a general strikeshut down the entire city.[68]

In 1917, following outrage over the election-year murder of a Philadelphia police officer, led to the shrinking of theCity Councilfrom two houses to just one.[69]In July 1919, Philadelphia was one of more than 36 industrial cities nationally to suffer arace riotduringRed Summerin post-World War Iunrest as recent immigrants competed with Blacks for jobs. In the 1920s, the public flouting ofProhibitionlaws,organized crime, mob violence, and corrupt police involvement in illegal activities led to the appointment ofBrig. Gen.Smedley Butlerof theU.S. Marine Corpsas the city's director of public safety, but political pressure still prevented long-term success in fighting crime and corruption.[70]

In 1940,non-Hispanic whitesconstituted 86.8% of the city's population.[71]In 1950, the population peaked at more than two million residents, then began to decline with the restructuring of industry that led to the loss of many middle-class union jobs. In addition, suburbanization enticed many affluent residents to depart the city for its outlying railroad commuting towns and newer housing. The resulting reduction in Philadelphia's tax base and the resources of local government caused the city to struggle through a long period of adjustment, and it approached bankruptcy by the late 1980s.[72][73]

In 1985, theMOVE Bombingof theCobbs Creekneighborhood by city helicopters occurred, killing 11 and destroying 61 homes.[74]

Revitalization andgentrificationof neighborhoods began in the late 1970s and continues into the 21st century with much of the development occurring in theCenter CityandUniversity Cityneighborhoods. But this expanded a shortage ofaffordable housingin the city. After many manufacturers and businesses left Philadelphia or shut down, the city started attracting service businesses and began to market itself more aggressively as a tourist destination. Contemporary glass-and-graniteskyscraperswere built in Center City beginning in the 1980s. Historic areas such asOld CityandSociety Hillwere renovated during the reformist mayoral era of the 1950s through the 1980s, making both areas among the most desirable Center City neighborhoods. Immigrants from around the world began to enter the U.S. through Philadelphia as their gateway, leading to a reversal of the city's population decline between 1950 and 2000, during which it lost about 25 percent of its residents.[75][76]

21st century

Philadelphia eventually began experiencing a growth in its population in 2007, which continued with incremental annual increases through the present.[77][78]A migration pattern has been established from New York City to Philadelphia by residents opting for a large city with relative proximity and a lowercost of living.[79][80]

Geography

Topography

Philadelphia's geographic center is about 40° 0′ 34″ north latitude and 75° 8′ 0″ west longitude. The40th parallel northpasses through neighborhoods inNortheast Philadelphia,North Philadelphia, andWest PhiladelphiaincludingFairmount Park. The city encompasses 142.71 square miles (369.62 km2), of which 134.18 square miles (347.52 km2) is land and 8.53 square miles (22.09 km2), or 6%, is water.[81]Natural bodies of water include theDelawareandSchuylkillrivers, lakes inFranklin Delano Roosevelt Park, andCobbs,Wissahickon, andPennypackcreeks. The largest artificial body of water is East Park Reservoir inFairmount Park.

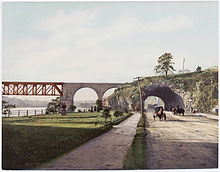

The lowest point is sea level and the highest point is inChestnut Hill, about 446 feet (136 m) above sea level on Summit Street near the intersection of Germantown Avenue andBethlehem Pikeat: 40.07815 N, 75.20747 W.[82][83]Philadelphia is located on theAtlantic Seaboard Fall Linethat separates theAtlantic Plainfrom thePiedmont.[84]The Schuylkill River's rapids atEast Fallswere inundated by completion of the dam atFairmount Water Works.[85]

The city is the seat ofits own county. The city is bordered by six adjacent counties:Montgomeryto the northwest;Bucksto the north and northeast;Burlington County, New Jerseyto the east;Camden County, New Jerseyto the southeast;Gloucester County, New Jerseyto the south; andDelaware Countyto the southwest.

Cityscape

City planning

Philadelphia was created in the 17th century, following the plan byWilliam Penn's surveyorThomas Holme.Center Cityis structured with long, straight streets running nearly due east–west and north–south, forming a grid pattern between theDelawareandSchuylkillrivers that is aligned with their courses. The original city plan was designed to allow for easy travel and to keep residences separated by open space that would help prevent the spread of fire.[86]In keeping with the idea of a "Greene Countrie Towne", and inspired by the many types of trees that grew in the region, Penn named many of the east–west streets for local trees.[87]Penn planned the creation of five public parks in the city which were renamed in 1824.[86]Centre Square was renamedPenn Square;[88]Northeast Square was renamedFranklin Square; Southeast Square was renamedWashington Square; Southwest Square was renamedRittenhouse Square; and Northwest Square was renamedLogan Circle/Square.[89]Center Cityhad an estimated 183,240 residents as of 2015[update], making it the second-most populated downtown area in the United States afterMidtown Manhattanin New York City.[90]

Philadelphia's neighborhoods are divided into six large sections that surround Center City:North Philadelphia,Northeast Philadelphia,South Philadelphia,Southwest Philadelphia,West Philadelphia, andNorthwest Philadelphia. The city's geographic boundaries have been largely unchanged since these neighborhoods were consolidated in 1854. However, each of these large areas contains numerous neighborhoods, some of whose boundaries derive from the boroughs, townships, and other communities that constitutedPennsylvania Countybefore their inclusion within the city.[91]

TheCity Planning Commission, tasked with guiding growth and development of the city, has divided the city into 18 planning districts as part of the Philadelphia2035 physical development plan.[92][93]Much of the city's 1980 zoning code was overhauled from 2007 to 2012 as part of a joint effort between former mayorsJohn F. StreetandMichael Nutter. The zoning changes were intended to rectify incorrect zoning maps to facilitate future community development, as the city forecasts an additional 100,000 residents and 40,000 jobs will be added by 2035.

ThePhiladelphia Housing Authority(PHA) is the largest landlord in Pennsylvania. Established in 1937, the PHA is the nation's fourth-largest housing authority, serving about 81,000 people with affordable housing, while employing 1,400 on a budget of $371 million.[94]ThePhiladelphia Parking Authorityis responsible for ensuring adequate parking for city residents, businesses, and visitors.[95]

Architecture

Philadelphia's architectural history dates back tocolonialtimes and includes a wide range of styles. The earliest structures were constructed withlogs, but brick structures were common by 1700. During the 18th century, thecityscapewas dominated byGeorgian architecture, includingIndependence HallandChrist Church.

In the first decades of the 19th century,FederalandGreek Revival architecturewere the dominant styles produced by Philadelphia architects such asBenjamin Latrobe,William Strickland,John Haviland,John Notman,Thomas Walter, andSamuel Sloan.[96]Frank Furnessis considered Philadelphia's greatest architect of the second half of the 19th century. His contemporaries includedJohn McArthur Jr.,Addison Hutton,Wilson Eyre, theWilson Brothers, andHorace Trumbauer. In 1871, construction began on theSecond Empire-stylePhiladelphia City Hall. ThePhiladelphia Historical Commissionwas created in 1955 to preserve the cultural and architectural history of the city. The commission maintains thePhiladelphia Register of Historic Places, adding historic buildings, structures, sites, objects and districts as it sees fit.[97]

In 1932, Philadelphia became home to the first modernInternational Styleskyscraper in the United States, thePSFS Building, designed byGeorge HoweandWilliam Lescaze. The 548 ft (167 m) City Hall remained the tallest building in the city until 1987 whenOne Liberty Placewas completed. Numerous glass and granite skyscrapers were built in Center City beginning in the late 1980s. In 2007, theComcast Centersurpassed One Liberty Place to become the city's tallest building. TheComcast Technology Centerwas completed in 2018, reaching a height of 1,121 ft (342 m), as thetallest building in the United Statesoutside ofManhattanand Chicago.[98]

For much of Philadelphia's history, the typical home has been therow house. The row house was introduced to the United States via Philadelphia in the early 19th century and, for a time, row houses built elsewhere in the United States were known as "Philadelphia rows".[96]A variety of row houses are found throughout the city, from Federal-style continuous blocks inOld CityandSociety Hillto Victorian-style homes inNorth Philadelphiato twin row houses inWest Philadelphia. While newer homes have been built recently, much of the housing dates to the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries, which has created problems such asurban decayand vacant lots. Some neighborhoods, includingNorthern Libertiesand Society Hill, have been rehabilitated throughgentrification.[99][100]

-

Elfreth's Alley, first developed in 1703, is the nation's oldest residential street. [101]

-

Carpenters' Hall, built between 1770 and 1774 in Georgian architecturestyle

-

The Second Bank of the United States, built between 1818 and 1824, exhibiting Greek Revival architecture

-

The Art Deco-style grand concourseat 30th Street Station, one of the nation's busiest passenger train stations, built between 1927 and 1933

Parks

As of 2014[update], the city's total park space, including municipal, state, and federal parks in the city, amounts to 11,211 acres (17.5 sq mi).[27]Philadelphia's largest park isFairmount Park, which includes thePhiladelphia Zooand encompasses 2,052 acres (3.2 sq mi) of the total parkland. Fairmount Park's adjacentWissahickon Valley Parkcontains 2,042 acres (3.2 sq mi).[102]Fairmount Park, when combined with Wissahickon Valley Park, is one of the largest contiguousurban parkareas in the U.S.[27]The two parks, along with theColonial Revival,GeorgianandFederal-stylemansionsin them, have been listed as one entity on theNational Register of Historic Placessince 1972.[103]

Climate

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Within theKöppen climate classification, Philadelphia falls under the northern periphery of thehumid subtropical climatezone (KöppenCfa).[104]Within theTrewartha climate classification, Philadelphia has atemperatemaritime climate(Do) limited to the north by thecontinental climate(Dc).[105]Summers are typically hot and muggy. Fall and spring are generally mild, and winter is moderately cold. The plant lifehardiness zonesare 7a and 7b, reflecting an average annual extreme minimum temperature between 0 and 10 °F (−18 and −12 °C).[106]

Snowfall is highly variable. Some winters have only light snow while others include major snowstorms. The normal seasonal snowfall averages 22.4 in (57 cm), with rare snowfalls in November or April, and rarely any sustained snow cover.[107]Seasonal snowfall accumulation has ranged from trace amounts in 1972–73, to 78.7 inches (200 cm) in the winter of 2009–10.[107][b]The city'sheaviest single-storm snowfallwas 30.7 in (78 cm), which occurred in January 1996.[108]

Precipitation is generally spread throughout the year, with eight to eleven wet days per month,[109]at an average annual rate of 44.1 inches (1,120 mm), but historically ranging from 29.31 in (744 mm) in 1922 to 64.33 in (1,634 mm) in 2011.[107]The most rain recorded in one day occurred on July 28, 2013, when 8.02 in (204 mm) fell atPhiladelphia International Airport.[107]Philadelphia has a moderately sunny climate with an average of 2,498hours of sunshineannually. The percentage of sunshine ranges from 47% in December to 61% in June, July, and August.[110]

The January daily average temperature is 33.7 °F (0.9 °C). The temperature frequently rises to 50 °F (10 °C) during thaws. July averages 78.7 °F (25.9 °C). Heat waves accompanied by high humidity andheat indicesare frequent, with highs reaching or exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) on 30 days of the year. The average window for freezing temperatures is November 6 to April 2,[107]allowing a growing season of 217 days. Early fall and late winter are generally dry, with February having the lowest average precipitation at 2.75 inches (70 mm). The dewpoint in the summer averages between 59.1 and 64.5 °F (15 and 18 °C).[107]

The highest recorded temperature was 106 °F (41 °C) on August 7, 1918. Temperatures at or above 100 °F (38 °C) are not common, with the last occurrence of such a temperature being July 21, 2019.[111]The lowest officially recorded temperature was −11 °F (−24 °C) on February 9, 1934.[111]Temperatures at or below 0 °F (−18 °C) are rare, with the last such occurrence beingJanuary 19, 1994.[107]The record low maximum is 5 °F (−15 °C) on February 10, 1899, and December 30, 1880. The record high minimum is 83 °F (28 °C) on July 23, 2011, and July 24, 2010.[112]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

79 (26) |

87 (31) |

95 (35) |

97 (36) |

102 (39) |

104 (40) |

106 (41) |

102 (39) |

96 (36) |

84 (29) |

73 (23) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 63.3 (17.4) |

63.5 (17.5) |

73.8 (23.2) |

84.3 (29.1) |

90.2 (32.3) |

94.8 (34.9) |

97.1 (36.2) |

94.8 (34.9) |

90.6 (32.6) |

82.6 (28.1) |

72.4 (22.4) |

64.2 (17.9) |

98.1 (36.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 41.3 (5.2) |

44.3 (6.8) |

52.8 (11.6) |

64.7 (18.2) |

74.4 (23.6) |

83.2 (28.4) |

87.8 (31.0) |

85.8 (29.9) |

78.9 (26.1) |

67.2 (19.6) |

55.9 (13.3) |

46.0 (7.8) |

65.2 (18.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.7 (0.9) |

35.9 (2.2) |

43.6 (6.4) |

54.5 (12.5) |

64.3 (17.9) |

73.5 (23.1) |

78.7 (25.9) |

76.8 (24.9) |

69.9 (21.1) |

58.2 (14.6) |

47.4 (8.6) |

38.6 (3.7) |

56.3 (13.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.0 (−3.3) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

34.3 (1.3) |

44.3 (6.8) |

54.2 (12.3) |

63.9 (17.7) |

69.6 (20.9) |

67.9 (19.9) |

60.9 (16.1) |

49.2 (9.6) |

38.8 (3.8) |

31.2 (−0.4) |

47.3 (8.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 10.7 (−11.8) |

13.7 (−10.2) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

33.0 (0.6) |

43.1 (6.2) |

53.2 (11.8) |

62.2 (16.8) |

60.3 (15.7) |

49.5 (9.7) |

37.1 (2.8) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

8.6 (−13.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−11 (−24) |

5 (−15) |

14 (−10) |

28 (−2) |

44 (7) |

51 (11) |

44 (7) |

35 (2) |

25 (−4) |

8 (−13) |

−5 (−21) |

−11 (−24) |

| Averageprecipitationinches (mm) | 3.13 (80) |

2.75 (70) |

3.96 (101) |

3.47 (88) |

3.34 (85) |

4.04 (103) |

4.38 (111) |

4.29 (109) |

4.40 (112) |

3.47 (88) |

2.91 (74) |

3.97 (101) |

44.11 (1,120) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.1 (18) |

8.4 (21) |

3.6 (9.1) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

3.5 (8.9) |

23.1 (59) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 0.01 in) | 11.0 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 10.9 | 11.0 | 10.3 | 10.1 | 8.9 | 9.3 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 11.0 | 120.8 |

| Average snowy days(≥ 0.1 in) | 4.1 | 3.8 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.8 | 12.0 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 66.2 | 63.6 | 61.7 | 60.4 | 65.4 | 67.8 | 69.6 | 70.4 | 71.6 | 70.8 | 68.4 | 67.7 | 67.0 |

| Averagedew point°F (°C) | 19.8 (−6.8) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

37.0 (2.8) |

49.5 (9.7) |

59.2 (15.1) |

64.6 (18.1) |

63.7 (17.6) |

57.2 (14.0) |

45.7 (7.6) |

35.6 (2.0) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

42.3 (5.7) |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 155.7 | 154.7 | 202.8 | 217.0 | 245.1 | 271.2 | 275.6 | 260.1 | 219.3 | 204.5 | 154.7 | 137.7 | 2,498.4 |

| Percentpossible sunshine | 52 | 52 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 61 | 61 | 61 | 59 | 59 | 52 | 47 | 56 |

| Averageultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Source 1:NOAA(relative humidity, dew point and sun 1961–1990)[115][110][107] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV index)[116] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Philadelphia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 41.8 (5.5) |

39.9 (4.4) |

41.2 (5.1) |

46.7 (8.2) |

53.9 (12.2) |

66.3 (19.0) |

74.0 (23.3) |

75.9 (24.4) |

71.4 (21.9) |

64.2 (17.9) |

55.1 (12.8) |

47.7 (8.8) |

56.5 (13.6) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Source: Weather Atlas[116] | |||||||||||||

Time Series

|

|

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on

Phabricatorand on

MediaWiki.org.

|

See or editraw graph data.

Air quality

Philadelphia County received anozonegrade of F and a 24-hourparticle pollutionrating of D in theAmerican Lung Association's 2017 State of the Air report, which analyzed data from 2013 to 2015.[117][118]The city was ranked 22nd for ozone, 20th for short-term particle pollution, and 11th for year-round particle pollution.[119]According to the same report, the city experienced a significant reduction in high ozone days since 2001—from nearly 50 days per year to fewer than 10—along with fewer days of high particle pollution since 2000—from about 19 days per year to about 3—and an approximate 30% reduction in annual levels of particle pollution since 2000.[118]

Five of the ten largestcombined statistical areas(CSAs) were ranked higher for ozone:Los Angeles(1st),New York City(9th),Houston(12th),Dallas(13th), andSan Jose, California(18th). Many smaller CSAs were also ranked higher for ozone, includingSacramento(8th),Las Vegas(10th),Denver(11th),El Paso(16th), andSalt Lake City(20th). Only two of those same ten CSAs, San Jose and Los Angeles, were ranked higher than Philadelphia for both year-round and short-term particle pollution.[119]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1683 | 600 | — |

| 1731 | 12,000 | +1900.0% |

| 1790 | 28,522 | +137.7% |

| 1800 | 41,220 | +44.5% |

| 1810 | 53,722 | +30.3% |

| 1820 | 63,802 | +18.8% |

| 1830 | 80,462 | +26.1% |

| 1840 | 93,665 | +16.4% |

| 1850 | 121,376 | +29.6% |

| 1860 | 565,529 | +365.9% |

| 1870 | 674,022 | +19.2% |

| 1880 | 847,170 | +25.7% |

| 1890 | 1,046,964 | +23.6% |

| 1900 | 1,293,697 | +23.6% |

| 1910 | 1,549,008 | +19.7% |

| 1920 | 1,823,779 | +17.7% |

| 1930 | 1,950,961 | +7.0% |

| 1940 | 1,931,334 | −1.0% |

| 1950 | 2,071,605 | +7.3% |

| 1960 | 2,002,512 | −3.3% |

| 1970 | 1,948,609 | −2.7% |

| 1980 | 1,688,210 | −13.4% |

| 1990 | 1,585,577 | −6.1% |

| 2000 | 1,517,550 | −4.3% |

| 2010 | 1,526,006 | +0.6% |

| 2020 | 1,603,797 | +5.1% |

| 2023 | 1,550,542 | −3.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[120] 2010–2020[11] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[121] |

||

As of the2020 U.S. Census, there were 1,603,797 people residing in Philadelphia, representing a 1.2% increase from the 2019 census estimate.[78]The racial composition of the city was 39.3% Black alone (42.0% Black alone or in combination), 36.3% White alone (41.9% White alone or in combination), 8.7% Asian alone, 0.4% American Indian and Alaska Native alone, 8.7% some other race, and 6.9% multiracial. 14.9% of residents were Hispanic or Latino.[122]

34.8% had a bachelor's degree or higher. 23.9% spoke a language other than English at home, the most common of which was Spanish (10.8%). 15.0% of the populations foreign born, roughly half of whom are naturalized U.S. citizens. 3.7% of the population are veterans. The median household income was $52,889 and 22.8% of the population lived in poverty. 49.5% of the population drove alone to work, while 23.2% used public transit, 8.2% carpooled, 7.9% walked, and 7.0% worked from home. The average commute is 31 minutes.[122]

After the1950 census, when a record high of 2,071,605 was recorded, the city's population began a long decline. The population dropped to a low of 1,488,710 residents in 2006 before beginning to rise again. Between 2006 and 2017, Philadelphia added 92,153 residents. In 2017, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated that the racial composition of the city was 41.3% Black (non-Hispanic), 34.9% White (non-Hispanic), 14.1% Hispanic or Latino, 7.1% Asian, 0.4% Native American, 0.05% Pacific Islander, and 2.8% multiracial.[123]

| Census racial composition | 2020[122] | 2010[124] | 2000 | 1990[125] | 1980[125] | 1970[125] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black or African American(non-Hispanic) | 38.3% | 42.2% | 42.6% | 39.3% | 37.5% | 33.3%[e] |

| White(non-Hispanic) | 34.3% | 36.9% | 42.5% | 52.1% | 57.1% | 63.8[e] |

| Hispanic or Latino(of any race) | 14.9% | 12.3% | 8.5% | 5.6% | 3.8% | 2.4%[e] |

| Asian | 8.3% | 6.3% | 4.5% | 2.7% | 1.1% | 0.3% |

| Pacific Islanders | 0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | <0.1% | ||

| Native Americans | 0.4% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Two or more races | 6.9% | 2.8% | 2.2% | n/a[126] | n/a | n/a |

Immigration and cultural diversity

In addition to the city's economic growth, the city's population has been fueled by foreign immigration. According toThe Pew Charitable Trusts, the city'sforeign-bornpopulation increased by 69% between 2000 and 2016 to constitute nearly 20% of Philadelphia's workforce,[127]and it doubled between 1990 and 2017 to constitute 13.8% of the city's total population, with the top five countries of origin being China by a significant margin followed by theDominican Republic,Jamaica,India, andVietnam.[128]

| Country | Population |

|---|---|

| 22,140 | |

| 13,792 | |

| 13,500 | |

| 11,382 | |

| 10,132 | |

| 9,186 | |

| 7,823 | |

| 6,898 | |

| 5,258 | |

| 4,385 |

Irish, Italian, German, Polish, English, Russian, Ukrainian, and French ancestries constitute the largestEuropeanethnic groups in the city.[130]Philadelphia has the second-largest Irish and Italian populations in the United States afterNew York City.South Philadelphiaremains one of the largestItalianneighborhoods in the country and is home to theItalian Market.

ThePennsportneighborhood andGray's Ferrysection of South Philadelphia, home to manyMummerclubs, are well known asIrishneighborhoods. TheKensington,Port Richmond, andFishtownneighborhoods have historically been heavily Irish and Polish. Port Richmond is a center for the Polish-American community in Philadelphia, and it remains a common destination for Polish immigrants.Northeast Philadelphia, although known for its Irish and Irish-American population, is home to a Jewish and Russian population.Mount AiryinNorthwest Philadelphiaalso contains a Jewish community. NearbyChestnut Hillis historically known as anAnglo-Saxon Protestantcommunity.

Philadelphia'sBlack Americanpopulation is the fourth-largest in the country after New York City,Chicago, andHouston.West PhiladelphiaandNorth Philadelphiaare largely African-American neighborhoods, but many are leaving those areas in favor of the Northeast and Southwest sections of Philadelphia. A higher proportion ofAfrican-American Muslimsreside in Philadelphia than most other major U.S. cities. West Philadelphia andSouthwest Philadelphiaare home to variousAfro-CaribbeanandAfrican immigrantcommunities.[131]

ThePuerto Ricanpopulation in Philadelphia is the second-largest on the U.S. mainland after New York City, and the second-fastest growing afterOrlando.[132]Eastern North Philadelphia, particularlyFairhilland surrounding areas to the north and east, has one of the highest concentrations of Puerto Ricans outsidePuerto Rico, with many large swaths of blocks being close to 100% Puerto Rican.[133][134]Puerto Rican andDominicanpopulations reside inNorth Philadelphiaand the Northeast, andMexicanand Central American populations exist in South Philadelphia.[135]South Americanmigrants were being transported by bus fromTexasto Philadelphia beginning in 2022.[136]

Philadelphia'sAsian Americanpopulation includes those of Chinese, Indians, Vietnamese, South Koreans, Filipinos, Cambodians, and Indonesians. Over 35,000 Chinese Americans lived in the city in 2015,[137]including aFuzhounesepopulation. Center City hosts aChinatownthat is served byChinatown bus lineswith service to/fromChinatown, Manhattan.[138]A Korean community initially settled in the North Philadelphia neighborhood ofOlney; however, the primaryKoreatownhas subsequently shifted further north, straddling the city's border with adjacentCheltenhaminMontgomery CountyandCherry HillinSouth Jersey. South Philadelphia is home toVietnamese-AmericansinLittle SaigonandCambodian-AmericansinCambodia Town, as well asThai-American,Indonesian-American, andChinese-Americancommunities.

Philadelphia'sGay villagenearWashington Squareis home to a concentration of gay and lesbian-friendly businesses, restaurants, and bars.[139][140]

Religion

In a 2014 study by thePew Research Center, 68% of the population of the city identified themselves asChristian.[141]Approximately 41% of Christians in the city and area professed attendance at a variety of churches that could be consideredProtestant, while 26% professedCatholicbeliefs.

TheProtestantChristian community in Philadelphia is dominated bymainline Protestant denominationsincluding theEvangelical Lutheran Church in America,United Church of Christ, theEpiscopal Church in the United States,Presbyterian Church (USA)andAmerican Baptist Churches USA. One of the most prominent mainline Protestant jurisdictions is theEpiscopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. TheAfrican Methodist Episcopal Churchwas established in Philadelphia. Historically, the city has strong connections to theQuakers,Unitarian Universalism, and theEthical Culture movement, all of which continue to be represented in the city. The QuakerFriends General Conferenceis based in Philadelphia. Evangelical Protestants making up less than 15% of the population were also prevalent.

Evangelical Protestant bodies included theAnglican Church in North America,Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod,Presbyterian Church in America, andNational Baptist Convention of America. The Catholic community is primarily served by theLatinCatholic Archdiocese of Philadelphia, theUkrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia, and theSyro-Malankara Catholic Eparchy of the United States of America and Canada, though someindependent Catholic churchesexist throughout Philadelphia and its suburbs. The Latin Church-based jurisdiction is headquartered in the city, and its see is theCathedral Basilica of Saints Peter and Paul. The Ukrainian Catholic jurisdiction is headquartered in Philadelphia, and is seated at theCathedral of the Immaculate Conception.

Less than 1% of Philadelphia's Christians wereMormons. The remainder of the Christian demographic is spread among smaller Protestant denominations and theEasternandOriental Orthodoxamong others. TheDiocese of Eastern Pennsylvania(Orthodox Church in America) andGreek Orthodox Archdiocese of America(Ecumenical Patriarchate) divide the Eastern Orthodox in Philadelphia. TheRussian OrthodoxSt. Andrew's Cathedralis in the city. The same study says that other religions collectively compose about 8% of the population, includingJudaism,Hinduism,Islam,Buddhism, andSikhism.[142]Philadelphia has the fifth-largestMuslimpopulation among U.S. cities.[143]The remaining 24% claimedno religious affiliation.

The Philadelphiametropolitan area'sJewishpopulation was estimated at 206,000 in 2001, which was the sixth-largest in the U.S. at that time.[144]Jewish traders were operating in southeastern Pennsylvania long beforeWilliam Penn. Jews in Philadelphia took a prominent part in theWar of Independence. Although the majority of the early Jewish residents were of Portuguese or Spanish descent, some among them had emigrated from Germany andPoland. About the beginning of the 19th century, a number of Jews from the latter countries, finding the services of theCongregation Mickvé Israelunfamiliar to them, resolved to form a new congregation which would use the ritual to which they had been accustomed.

African diasporic religionsare practiced in some Latino and Hispanic and Caribbean communities in North and West Philadelphia.[145][146]

Languages

As of 2010[update], 79.12% (1,112,441) of Philadelphia residents age 5 and older spoke English at home as aprimary language, while 9.72% (136,688) spoke Spanish, 1.64% (23,075) Chinese, 0.89% (12,499)Vietnamese, 0.77% (10,885) Russian, 0.66% (9,240) French, 0.61% (8,639)other Asian languages, 0.58% (8,217)African languages, 0.56% (7,933)Cambodian(Mon-Khmer), and Italian was spoken as amain languageby 0.55% (7,773) of the population over the age of five. In total, 20.88% (293,544) of Philadelphia's population age 5 and older spoke amother languageother than English.[147]

Poverty

Philadelphia is home to many food poverty programs, of which two of the largest arePhilabundancewhich claims to feed 90000 people per week.[148][149][150][151]andShare Food Programwhich claims to feed 1 million people per month.[152]

Economy

| Top publicly traded companies headquartered in Philadelphia |

||

| Corporation | 2019 rank |

Revenue (billions) |

| Comcast | 32 | 94.5 |

| Aramark | 198 | 15.8 |

| FMC | 556 | 4.7 |

| Urban Outfitters | 634 | 4.0 |

| Carpenter Technology | 940 | 2.2 |

| Source:Fortune[153] | ||

Philadelphia's close geographical and transportation connections to other large metropolitan economies along theEastern Seaboardof the United States have been cited as offering a significant competitive advantage for business creation andentrepreneurship.[154]The city is the center of economic activity in bothPennsylvaniaand the four-stateDelaware Valleymetropolitan region. FiveFortune 500companies are headquartered in the city. As of 2021[update], the Philadelphia metropolitan area is estimated to produce agross metropolitan product(GMP) of US$479 billion,[155]an increase from the $445 billion calculated by theBureau of Economic Analysisfor 2017,[156]representing theninth-largest U.S. metropolitan economy.

Philadelphia's economic sectors includefinancial services, health care,biotechnology, information technology, trade and transportation, manufacturing,oil refining,food processing, and tourism. Metropolitan Philadelphia is one of the top five Americanventure capitalhubs, credited to its proximity to New York City'sfinancialandtech and biotechnology ecosystems.[21]Financial activities account for the largest economic sector of the metropolitan area, which is one of the largesthealth educationand research centers in the United States. The city's two largest employers are the federal and city governments. Philadelphia's largest private employer is theUniversity of Pennsylvania, followed by theChildren's Hospital of Philadelphia.[157]A study commissioned by the city's government in 2011 projected 40,000 jobs would be added to the city within 25 years, raising the number of jobs from 675,000 in 2010 to an estimated 715,000 by 2035.[158]

Corporations

ThePhiladelphia Stock Exchange, acquired byNasdaqin 2007, is a global leader inoptionstrading.[22]The city is home to the headquarters of cable television andinternet service providerComcast, insurance companiesCigna,Colonial Penn, andIndependence Blue Cross, food services companyAramark, chemical makersFMC CorporationandRohm and Haas, pharmaceutical companiesGlaxoSmithKline,Amicus Therapeutics,Spark Therapeutics,apparelretailersFive BelowandUrban Outfittersand its subsidiaryAnthropologie, automotive parts retailerPep Boys, and stainless steel producerCarpenter Technology Corporation.

Other corporation headquarters in the city includeRiteAid,Crown Holdings, andBrandywine Realty Trust. The headquarters ofBoeing Rotorcraft Systemsand its mainrotorcraftfactory are in the Philadelphia suburb ofRidley Park;The Vanguard Group, and the U.S. headquarters ofSiemens Healthineersare headquartered inMalvern, Pennsylvania, a Philadelphia suburb.HealthcareconglomerateAmerisourceBergenis located in suburbanConshohocken, Pennsylvania. Across theDelaware Riverin adjacentCamden County, New Jersey,Campbell Soup CompanyandSubaru USAare both headquartered in the city ofCamden, andTD Bank (USA)is headquartered innearbysuburbanCherry Hill, New Jersey.

Tech and biotech

Philadelphia is a hub forinformation technologyandbiotechnology.[160]Philadelphia and Pennsylvania are attracting newlife sciencesventures.[161]The Philadelphia metropolitan area, comprising the Delaware Valley, has become a growing hub forventure capitalfunding.[161]

Tourism

Philadelphia's history attracts many tourists, with theIndependence National Historical Park, which includes theLiberty Bell,Independence Hall, and other historic sites, received over 5 million visitors in 2016.[162]The city welcomed 42 million domestic tourists in 2016 who spent $6.8 billion, generating an estimated $11 billion in total economic impact in the city and surrounding four counties of Pennsylvania.[28]The annualNaked Bike Rideattracts participants from around the United States and internationally to Philadelphia.

Trade and transportation

Philadelphia International Airportis undergoing a $900 millioninfrastructuralexpansion to increase passenger capacity and augment passenger experience;[163][164]while thePort of Philadelphia, having experienced the highest percentage growth bytonnageloaded in 2017 among major U.S. seaports, was in the process of doubling its shippingcapacityto accommodate super-sizedpost-Panamaxshipping vessels in 2018.[165]Philadelphia's30th Street Stationis the third-busiestAmtrakrail hub, followingPenn StationinManhattanandUnion Stationin Washington, D.C., transporting over 4 millioninter-city railpassengers annually.[166]

Education

Primary and secondary education

Education in Philadelphia is provided by many private and public institutions. TheSchool District of Philadelphiais the local school district, operatingpublic schools, in all of the city.[167]The Philadelphia School District is the eighth-largestschool districtin the nation[168]with 142,266 students in 218 traditional public schools and 86charter schoolsas of 2014[update].[169]

The city's K-12 enrollment in district–run schools dropped from 156,211 students in 2010 to 130,104 students in 2015. During the same time period, the enrollment in charter schools increased from 33,995 students in 2010 to 62,358 students in 2015.[157]This consistent drop in enrollment led the city to close 24 of its public schools in 2013.[170]During the 2014 school year, the city spent an average of $12,570 per pupil, below the average among comparable urban school districts.[157]

Graduation rates among district-run schools, meanwhile, steadily increased in the ten years from 2005. In 2005, Philadelphia had a district graduation rate of 52%. This number increased to 65% in 2014, still below the national and state averages. Scores on the state's standardized test, thePennsylvania System of School Assessment(PSSA) trended upward from 2005 to 2011 but subsequently decreased. In 2005, the district-run schools scored an average of 37.4% on math and 35.5% on reading. The city's schools reached their peak scores in 2011 with 59.0% on math and 52.3% on reading. In 2014, the scores dropped significantly to 45.2% on math and 42.0% on reading.[157]

Of the city's public high schools, including charter schools, only four performed above the national average on theSAT(1497 out of 2400[171]) in 2014:Masterman,Central,Girard Academic Music Program, andMaST Community Charter School. All other district-run schools were below average.[157]

Higher education

Medical and research facilities of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine and theChildren's Hospital of Philadelphia. Philadelphia has the third-largest student concentration on theEast Coast, with more than 120,000 college and university students enrolled within the city and nearly 300,000 in the metropolitan area.[172]More than 80 colleges, universities, trade, and specialty schools are in the Philadelphia region. One of the founding members of theAssociation of American Universitiesis in the city, theUniversity of Pennsylvania, anIvy Leagueinstitution with claims to be theFirst university in the United States.[173][38]

The city's largest university by student enrollment isTemple University, followed byDrexel University.[174]The city's nationally ranked research universities comprise the University of Pennsylvania, Temple University, Drexel University, andThomas Jefferson University. Philadelphia is also home to five schools of medicine:Drexel University College of Medicine,Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania,Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine,Temple University School of Medicine, and Thomas Jefferson University'sSidney Kimmel Medical College. Hospitals, universities, and higher education research institutions in Philadelphia's four congressional districts received more than $252 million inNational Institutes of Healthgrants in 2015.[175]

Other institutions of higher learning within the city's borders include:

- Chestnut Hill College

- Community College of Philadelphia

- Curtis Institute of Music

- Holy Family University

- La Salle University

- Moore College of Art and Design

- Peirce College

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

- Saint Joseph's University

- The Restaurant School at Walnut Hill College

- University of the Arts

Culture

Philadelphia is home to manynational historical sitesthat relate to the founding of the United States.Independence National Historical Parkis the center of these historical landmarks and one of the country's 22UNESCOWorld Heritage Sites.Independence Hall, where theDeclaration of Independencewas signed, and theLiberty Bellis housed, are among the city's most popular attractions. Other national historic sites include the homes ofEdgar Allan PoeandThaddeus Kosciuszko, and early government buildings, including theFirstand theSecond Bank of the United States,Fort Mifflin, and theGloria Dei (Old Swedes') Church.[176]Philadelphia alone has 67National Historic Landmarks, the third most of any city in the country.[176]

Philadelphia's major science museums include theFranklin Institute, which contains theBenjamin Franklin National Memorial, theAcademy of Natural Sciences, theMütter Museum, and theUniversity of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. History museums include theNational Constitution Center, theMuseum of the American Revolution, thePhiladelphia History Museum, theNational Museum of American Jewish History, theAfrican American Museum in Philadelphia, theHistorical Society of Pennsylvania, the Masonic Library and Museum of Pennsylvania in theMasonic Temple, and theEastern State Penitentiary. Philadelphia is home to the United States's firstzoo[177]andhospital,[178]as well asFairmount Park, one of America's oldest and largest urban parks,[27]founded in 1855.[179]

The city is home to important archival repositories, including theLibrary Company of Philadelphia, established in 1731 byBenjamin Franklinat 1314Locust Street,[180]and theAthenaeum of Philadelphia, founded in 1814.[181]ThePresbyterian Historical Societyis the country's oldest denominational historical society, organized in 1852.[182]

Arts

The city is home to multiple art museums, including thePennsylvania Academy of the Fine Artsand theRodin Museum, which holds the largest collection of work byAuguste Rodinoutside France. The city's largest art museum, thePhiladelphia Museum of Art, is one of thelargest art museums in the world. The long flight ofstepsto the Art Museum's main entrance became famous after the filmRocky(1976).[183]

Annual events include thePhiladelphia Film Festival, held annually each October, the6abc Dunkin' Donuts Thanksgiving Day Parade, the nation's longest-running continuously heldThanksgiving Dayparade, and theMummers Parade, the nation's longest continuously held folk parade, which is held everyNew Year's Daypredominantly onBroad Street.

Areas such asSouth Streetand theOld Citysection of the city have a vibrant night life. TheAvenue of the ArtsinCenter Citycontains many restaurants and theaters, such as theKimmel Center for the Performing Arts, home of thePhiladelphia Orchestra, and theAcademy of Music, home ofOpera Philadelphiaand thePennsylvania Ballet.[183]TheWilma Theatreand thePhiladelphia Theatre Companyat theSuzanne Roberts Theatreproduce a variety of new plays.[184][185]Several blocks to the east are theLantern Theater CompanyatSt. Stephens Episcopal Church;[186]and theWalnut Street Theatre, aNational Historic Landmarkstated to be the oldest and most subscribed-totheatrein theEnglish-speaking world, founded in 1809.[187]In May 2019, the Walnut Street Theatre announced a major expansion to begin in 2020.[188]New Freedom Theatre, Pennsylvania's oldest African-American theatre, is located on North Broad Street.

Philadelphia has morepublic artthan any other American city.[189]In 1872, theAssociation for Public Art, formerly the Fairmount Park Art Association, was created as the first private association in the United States dedicated to integrating public art andurban planning.[190]In 1959, lobbying by the Artists Equity Association helped create thePercent for Artordinance, the first for a U.S. city.[191]The program, which has funded more than 200 pieces of public art, is administered by the Philadelphia Office of Arts and Culture, the city's art agency.[192]The city has more murals than any other American city, due to the 1984 creation of the Department of Recreation'sMural Arts Program, which seeks to beautify neighborhoods and provide an outlet forgraffitiartists. The program has funded more than 2,800muralsby professional, staff and volunteer artists and educated more than 20,000 youth in underserved neighborhoods throughout Philadelphia.[193]

The city is home to a number of art organizations, including the regional art advocacy nonprofit Philadelphia Tri-State Artists Equity,[194]thePhiladelphia Sketch Club, one of the country's oldest artists' clubs,[195]andThe Plastic Club, started by women excluded from the Sketch Club.[196]ManyOld Cityart galleries stay open late on theFirst Fridayevent of each month.[197]

Music

ThePhiladelphia Orchestrais generally considered one of thetop five orchestrasin the United States. The orchestra performs at theKimmel Center[198]and has asummer concert seriesat theMann Center for the Performing Arts.[199]Opera Philadelphiaperforms at the nation's oldest continually operating opera house—theAcademy of Music.[183]ThePhiladelphia Boys Choir & Choralehas performed its music all over the world.[200]ThePhilly Popsplays orchestral versions of popularjazz,swing,Broadway, andbluessongs at the Kimmel Center and other venues within themid-Atlanticregion.[201]TheCurtis Institute of Musicis one of the world's premierconservatoriesand among the most selective institutes of higher education in the nation.[202]

Philadelphia has played a prominent role in themusic of the United States. The culture ofAmerican popular musichas been influenced by significant contributions of Philadelphia area musicians and producers, in both the recording and broadcasting industries. In 1952, the teen dance party program calledBandstandpremiered on local television, hosted byBob Horn. The show was renamedAmerican Bandstandin 1957, when it began national syndication onABC, hosted byDick Clarkand produced in Philadelphia until 1964 when it moved to Los Angeles.[203]Promoters marketed youthful musical artists known asteen idolsto appeal to the young audience. Philadelphia-born singers such asFrankie Avalon,James Darren,Eddie Fisher,Fabian Forte, andBobby Rydell, along withSouth Philly-raisedChubby Checker, topped the music charts, establishing a clean-cutrock and rollimage.

Philly soulmusic of the late 1960s–1970s is a highly produced version ofsoul musicwhich led to later forms of popular music such asdiscoandurban contemporaryrhythm and blues.[204]On July 13, 1985,John F. Kennedy Stadiumwas the American venue for theLive Aidconcert.[205]The city also hosted theLive 8concert, which attracted about 700,000 people to theBenjamin Franklin Parkwayon July 2, 2005.[206]

Notable rock and pop musicians from Philadelphia and its suburbs includeBill Haley & His Comets,Nazz,Todd Rundgren,Hall & Oates,the Hooters,Cinderella,DJ Jazzy Jeff & the Fresh Prince,Ween,Schoolly D,Pink,the Roots,Beanie Sigel,State Property,Lisa "Left Eye" Lopes,Meek Mill,Lil Uzi Vert, and others.

Cuisine

The city is known for itshoagies,stromboli,roast pork sandwich,scrapple,soft pretzels,water ice,Irish potato candy,tastykakes, and thecheesesteaksandwich which was developed by Italian immigrants.[207]The Philadelphia area has many establishments that serve cheesesteaks, including restaurants,taverns,delicatessensand pizza parlors.[208][209][210]The originator of the thinly-sliced steak sandwich in the 1930s, initially without cheese, isPat's King of Steaks, which faces its rivalGeno's Steaks, founded in 1966,[211]across the intersection of 9th Street and Passyunk Avenue in theItalian MarketofSouth Philadelphia.[212]

McGillin's Olde Ale House, opened in 1860 on Drury Street inCenter City, is the oldest continuously operated tavern in the city.[213]TheCity Tavernis a replica of a historic 18th-century building first opened in 1773, demolished in 1854 after a fire, and rebuilt in 1975 on the same site as part ofIndependence National Historical Park.[214]The tavern offers authentic 18th-century recipes, served in seven period dining rooms, three wine cellar rooms and an outdoor garden.[215]

TheReading Terminal Marketis a historicfood marketfounded in 1893 in theReading Terminalbuilding, a designated National Historic Landmark. The enclosed market is one of the oldest and largest markets in the country, hosting over a hundred merchants offeringPennsylvania Dutchspecialties,artisan cheeseand meat, locally grown groceries, and specialty and ethnic foods.[216]

Dialect

The traditional Philadelphia accent is considered by somelinguiststo be the most distinctive accent in North America.[217]The Philadelphia dialect, which is spread throughout theDelaware ValleyandSouth Jersey, is part of a largerMid-Atlantic American Englishfamily, a designation that also includes theBaltimore dialect. Additionally, it shares many similarities with theNew York accent. Owing to over a century of linguistic data collected by researchers at theUniversity of Pennsylvaniaunder sociolinguistWilliam Labov, the Philadelphia dialect has been one of the best-studied forms ofAmerican English.[218][219][f]The accent is especially found within the Irish American and Italian American working-class neighborhoods.[220]Philadelphia also has its own unique collection ofneologismsand slang terms.[221]

Sports

Philadelphia's first professional sports team was baseball'sAthletics, organized in 1860.[222]The Athletics were initially anamateur leagueteam thatturned professionalin 1871, and then became a founding team of the currentNational Leaguein 1876.[223]The city is one of 13 U.S. cities to have teams inall four major league sports: thePhiladelphia PhilliesofMajor League Baseball(MLB), thePhiladelphia Eaglesof theNational Football League(NFL), thePhiladelphia Flyersof theNational Hockey League(NHL), and thePhiladelphia 76ersof theNational Basketball Association(NBA).[224]The Phillies, formed in 1883 as the Quakers and renamed in 1884,[225]are the oldest team continuously playing under the same name in the same city in the history of American professional sports.[226]

The Philadelphia metro area is also home to thePhiladelphia UnionofMajor League Soccer(MLS). The Union began playing their home games in 2010 atPPLPark, asoccer-specific stadiuminChester, Pennsylvania.[227]The stadium's name was changed toTalen EnergyStadium in 2016[228]and toSubaru Parkin 2020.[229]

Philadelphia was the second of eight American cities to have won titles in all four major leagues (MLB, NFL, NHL and NBA), and also has a title in soccer from the now-defunctNorth American Soccer Leaguein the 1970s. The city's professional teams and their fans endured 25 years without a championship, from the 76ers1983 NBA Finalswin[230]until the Phillies2008 World Serieswin.[231][232]The lack of championships was sometimes attributed in jest to theCurse of Billy PennafterOne Liberty Placebecame the first building to surpass the height of theWilliam Pennstatue on top ofCity Hall'stower in 1987.[233]After nine years passed without another championship, the Eagles won their firstSuper Bowlfollowing the2017 season.[234]In 2004,ESPNplaced Philadelphia second on its list of The Fifteen Most Tortured Sports Cities.[235][236]Fans of the Eagles and Phillies were singled out as the worst fans in the country byGQmagazine in 2011, which used the subtitle of "Meanest Fans in America" to summarize incidents of drunken behavior and a history ofbooing.[237][238]

Major professional sports teams that originated in Philadelphia but later moved to other cities include theGolden State Warriorsbasketball team, which played in Philadelphia from 1946 to 1962[239]and theOakland Athleticsbaseball team, which was originally thePhiladelphia Athleticsand played in Philadelphia from 1901 to 1954.[240]

Philadelphia is home to professional, semi-professional, and elite amateur teams incricket,rugby league(Philadelphia Fight), andrugby union. Major running events in the city include thePenn Relays(track and field), thePhiladelphia Marathon, and theBroad Street Run. TheCollegiate Rugby Championshipis played every June atTalen Energy StadiuminChester.[241]

Rowing has been popular in Philadelphia since the 18th century.[242]Boathouse Rowis a symbol of Philadelphia's rich rowing history, and eachBig Fivemember has its own boathouse.[243]Philadelphia hosts numerous local and collegiate rowing clubs and competitions, including the annualDad Vail Regatta, which is the largestintercollegiate rowingevent inNorth Americawith more than 100 U.S. and Canadian colleges and universities participating;[244]the annualStotesbury Cup Regatta, which is billed as the world's oldest and largest rowing event for high school students;[245][246]and theHead of the Schuylkill Regatta.[247]The regattas are held on theSchuylkill Riverand organized by theSchuylkill Navy, an association of area rowing clubs that has produced numerousOlympic rowers.[248]

ThePhiladelphia Spinnerswere a professionalultimateteam inMajor League Ultimate(MLU) until 2016. The Spinners were one of the original eight teams of theAmerican Ultimate Disc League(AUDL) that began in 2012. They played atFranklin Fieldand won the inaugural AUDL championship and the final MLU championship in 2016.[249]The MLU was suspended indefinitely by its investors in December 2016.[250]As of 2018[update], thePhiladelphia Phoenixcontinue to play in the AUDL.[251]

Philadelphia is home to thePhiladelphia Big 5, a group of fiveNCAA Division Icollege basketballprograms. The Big 5 includeLa Salle,Penn,Saint Joseph's,Temple, andVillanovauniversities.[252]The sixth NCAA Division I school in Philadelphia isDrexel University. Villanova won the1985,[253]2016,[254]and2018[255]championship of theNCAA Division I men's basketball tournament. Philadelphia will be one of the eleven US host cities for the2026 FIFA World Cup.[256]

| Team | League | Sport | Venue | Capacity | Founded | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philadelphia Phillies | MLB | Baseball | Citizens Bank Park | 46,528 | 1883 | 1980, 2008 |

| Philadelphia Eagles | NFL | American football | Lincoln Financial Field | 69,176 | 1933 | 1948, 1949, 1960, 2017 |

| Philadelphia 76ers | NBA | Basketball | Wells Fargo Center | 21,600 | 1963 | 1966–67,1982–83 |

| Philadelphia Flyers | NHL | Ice hockey | Wells Fargo Center | 19,786 | 1967 | 1973–74,1974–75 |

| Philadelphia Union | MLS | Soccer | Subaru Park | 18,500 | 2010 | none |

| Philadelphia Wings | NLL | Lacrosse | Wells Fargo Center | 19,786 | 2018 | none |

Law and government

Philadelphia County is alegal nullity. All county functions were assumed by the city in 1952.[257]The city has been coterminous with the county since 1854.[63]

Philadelphia's 1952Home RuleCharterwas written by the City Charter Commission, which was created by thePennsylvania General Assemblyin an act of April 1949, and a city ordinance of June 1949. The existingcity councilreceived a proposed draft in February 1951, and the electors approved it in an election held in April 1951.[258]The first elections under the new Home Rule Charter were held in November 1951, and the newly elected officials took office in January 1952.[257]

The city uses thestrong-mayorversion of the mayor–council form of government, which is led by one mayor in whomexecutive authorityis vested. The mayor has the authority to appoint and dismiss members of all boards and commissions without the approval of the city council. Electedat-large, the mayor is limited to two consecutive four-year terms, but can run for the position again after an intervening term.[258]

Courts

Philadelphia Countyis coterminous with theFirst Judicial District of Pennsylvania. The Philadelphia CountyCourt of Common Pleasis thetrial courtofgeneral jurisdictionfor the city, hearingfelony-level criminal cases and civil suits above the minimum jurisdictional limit of $10,000. The court hasappellate jurisdictionover rulings from theMunicipaland Traffic Courts, and some administrative agencies and boards. The trial division has 70 commissioned judges elected by the voters, along with about one thousand other employees.[259]The court has a family division with 25 judges[260]and an orphans' court with three judges.[261]

As of 2018[update], the city'sDistrict AttorneyisLarry Krasner, a Democrat.[262]The last Republican to hold the office isRonald D. Castille, who left in 1991 and later served as the Chief Justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court from 2008 to 2014.[263]

ThePhiladelphia Municipal Courthandles traffic cases, misdemeanor and felony criminal cases with maximum incarceration of five years, and civil cases involving $12,000 or less ($15,000 in real estate and school tax cases), and all landlord-tenant disputes. The municipal court has 27 judges elected by the voters.[264]

Pennsylvania's threeappellate courtsalso have sittings in Philadelphia. TheSupreme Court of Pennsylvania, the court of last resort in the state, regularly hears arguments inPhiladelphia City Hall.[265]TheSuperior Court of Pennsylvaniaand theCommonwealth Court of Pennsylvaniaalso sit in Philadelphia several times a year.[266][267]Judges for these courts are elected at large.[268]The state Supreme Court and Superior Court have deputyprothonotaryoffices in Philadelphia.[269][270]

Philadelphia is home to the federalUnited States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvaniaand theCourt of Appeals for the Third Circuit, both of which are housed in theJames A. Byrne United States Courthouse.[271][272]

Politics

The current mayor isCherelle Parkerwho won the election in November 2023.[273]Parker's predecessor,Jim Kenney, served two terms from 2016 to January 2024.[274]Parker is a member of theDemocratic Party. For over seven decades, since 1952, everyPhiladelphia mayorhas been a Democrat.

Philadelphia City Councilis the legislative branch which consists of ten council members representing individual districts and seven members electedat-large, all of whom are elected to four-year terms.[275]Democrats are currently the majority and hold 14 seats including nine of the ten districts and five at-large seats. Republicans hold one seat: theNortheast-basedTenth District. TheWorking Families Partyholds two at-large seats making them the Council's minority party. The current council president isKenyatta Johnson.[276]

Philadelphia's political structure consists of a system of wards and divisions. There are 66 wards with 11 to 51 divisions each for a total of 1703 divisions. Each division elects two committee people who are supposed to live within the division boundaries, and committee people select a leader for their ward.[277]Democrats and Republicans elect their own committee people every four years. The committee person's role is to serve as a point of contact between voters and party officials and help get out the vote.[278]Most wards are closed which means the ward leader makes sole endorsement decisions; open wards allow committee people to weigh in on these decisions.[279]There are groups such asOpen Wards Philadelphiaand individuals who are working to elect ward leaders who promote an open ward system.[280]

Chart of voter registration

| Philadelphia County voter registration statistics as of March 4, 2024[281] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political Party | Total Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 775,851 | 75.00% | |||

| Republican | 117,639 | 11.37% | |||

| No Party Affiliation | 114,990 | 11.11% | |||

| Minor parties | 25,924 | 2.50% | |||

| Total | 1,034,404 | 100.00% | |||

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 132,870 | 17.86% | 604,175 | 81.21% | 6,921 | 0.93% |

| 2016 | 108,748 | 15.32% | 584,025 | 82.30% | 16,845 | 2.37% |

| 2012 | 96,467 | 13.97% | 588,806 | 85.24% | 5,503 | 0.80% |

| 2008 | 117,221 | 16.33% | 595,980 | 83.00% | 4,824 | 0.67% |

| 2004 | 130,099 | 19.30% | 542,205 | 80.44% | 1,765 | 0.26% |

| 2000 | 100,959 | 17.99% | 449,182 | 80.04% | 11,039 | 1.97% |

| 1996 | 85,345 | 16.00% | 412,988 | 77.44% | 34,944 | 6.55% |

| 1992 | 133,328 | 20.90% | 434,904 | 68.16% | 69,826 | 10.94% |

| 1988 | 219,053 | 32.45% | 449,566 | 66.60% | 6,358 | 0.94% |

| 1984 | 267,178 | 34.60% | 501,369 | 64.94% | 3,555 | 0.46% |

| 1980 | 244,108 | 33.99% | 421,253 | 58.66% | 52,739 | 7.34% |

| 1976 | 239,000 | 32.03% | 494,579 | 66.28% | 12,618 | 1.69% |

| 1972 | 344,096 | 43.89% | 431,736 | 55.07% | 8,138 | 1.04% |

| 1968 | 254,153 | 29.90% | 525,768 | 61.85% | 70,196 | 8.26% |

| 1964 | 239,733 | 26.24% | 670,645 | 73.42% | 3,094 | 0.34% |

| 1960 | 291,000 | 31.79% | 622,544 | 68.02% | 1,733 | 0.19% |

| 1956 | 383,414 | 42.97% | 507,289 | 56.85% | 1,618 | 0.18% |

| 1952 | 396,874 | 41.40% | 557,352 | 58.15% | 4,321 | 0.45% |

| 1948 | 425,962 | 48.12% | 432,699 | 48.88% | 26,636 | 3.01% |

| 1944 | 346,380 | 40.96% | 496,367 | 58.70% | 2,883 | 0.34% |

| 1940 | 354,878 | 39.81% | 532,149 | 59.69% | 4,459 | 0.50% |

| 1936 | 329,881 | 36.94% | 539,757 | 60.45% | 23,310 | 2.61% |

| 1932 | 331,092 | 54.54% | 260,276 | 42.88% | 15,651 | 2.58% |

| 1928 | 420,320 | 59.99% | 276,573 | 39.48% | 3,703 | 0.53% |

| 1924 | 347,457 | 77.73% | 54,213 | 12.13% | 45,352 | 10.15% |

| 1920 | 307,826 | 73.43% | 90,151 | 21.50% | 21,235 | 5.07% |

| 1916 | 194,163 | 66.81% | 90,800 | 31.25% | 5,638 | 1.94% |

| 1912 | 91,944 | 36.53% | 66,308 | 26.35% | 93,438 | 37.12% |

| 1908 | 185,263 | 69.09% | 75,310 | 28.09% | 7,568 | 2.82% |

| 1904 | 227,709 | 80.85% | 48,784 | 17.32% | 5,161 | 1.83% |

| 1900 | 173,657 | 73.93% | 58,179 | 24.77% | 3,053 | 1.30% |

| 1896 | 176,462 | 72.06% | 63,323 | 25.86% | 5,102 | 2.08% |

| 1892 | 116,685 | 57.45% | 84,470 | 41.59% | 1,947 | 0.96% |

| 1888 | 111,358 | 54.20% | 92,786 | 45.16% | 1,300 | 0.63% |

| 1884 | 101,288 | 58.00% | 71,288 | 40.82% | 2,057 | 1.18% |