Edinburgh

|

Edinburgh

Dùn Èideann

|

|

|---|---|

| City of Edinburgh | |

|

Skyline of Central Edinburgh, with the

Dugald Stewart Monument(forefront) and

Edinburgh Castle(background)

|

|

|

|

|

| Nicknames:

"

Auld Reekie", "

Edina", "

Athens of the North"

|

|

| Motto(s): | |

|

Edinburgh

localitywithin the

City of Edinburgh council area

|

|

| Coordinates:55°57′12″N03°11′21″W / 55.95333°N 3.18917°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | City of Edinburgh |

| Lieutenancy area | Edinburgh |

| Founded | Before 7th century AD |

| Burgh Charter | 1124 |

| City status | 1633[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Unitary authority |

| • Governing body | The City of Edinburgh Council |

| •Lord Provost of Edinburgh | Robert Aldridge |

| •MSPs |

|

| •MPs |

|

| Area | |

| •Locality | 46 sq mi (119 km2) |

| • Urban

(

Settlement)

[5]

|

49 sq mi (126 km2) |

| •Council area[6] | 102 sq mi (263 km2) |

| Elevation | 154 ft (47 m) |

| Population | |

| •Locality | 506,520 |

| • Density | 11,000/sq mi (4,300/km2) |

| •Urban

(

Settlement)

|

530,990 |

| • Urban density | 11,000/sq mi (4,200/km2) |

| •Metro | 901,455 |

| • Council area | 514,990[disputed–discuss] |

| • Council area density | 5,060/sq mi (1,955/km2) |

| • Language(s) | English Scots |

| GDP | |

| •Council area | £31.802 billion (2022) |

| • Per head | £60,764 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC±0(GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1(BST) |

| Postcode areas | |

| Area code | 0131 |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-EDH |

| ONS code | S12000036 |

| OS grid reference | NT275735 |

| NUTS3 | UKM25 |

| Primary Airport | Edinburgh Airport |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Old and New Towns of Edinburgh |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 728 |

| Inscription | 1995 (19thSession) |

| Official name | The Forth Bridge |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, iv |

| Reference | 1485 |

| Inscription | 2015 (39thSession) |

| Edinburgh |

|---|

|

Edinburgh(/ˈɛdɪnbərə/ED-in-bər-ə,[12][13][14]Scots:[ˈɛdɪnbʌrə];Scottish Gaelic:Dùn Èideann[t̪unˈeːtʲən̪ˠ]) is thecapital cityofScotlandand one of its 32council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by theFirth of Forthestuary and to the south by thePentland Hills. Edinburgh had a population of 506,520 in mid-2020,[8]making it thesecond-most populouscity in Scotland and theseventh-most populousin theUnited Kingdom. The wider metropolitan area has a population of 912,490.[15]

Recognised as the capital of Scotland since at least the 15th century, Edinburgh is the seat of theScottish Government, theScottish Parliament, thehighest courts in Scotland, and thePalace of Holyroodhouse, theofficial residenceof theBritish monarchin Scotland. It is also the annual venue of theGeneral Assembly of the Church of Scotland. The city has long been a centre of education, particularly in the fields of medicine,Scottish law, literature, philosophy, the sciences and engineering. TheUniversity of Edinburgh, founded in 1582 and now one of three in the city, is considered one of the best research institutions in the world. It is the second-largest financial centre in the United Kingdom, the fourth largest in Europe, and the thirteenth largest internationally.[16]

The city is a cultural centre, and is the home of institutions including theNational Museum of Scotland, theNational Library of Scotlandand theScottish National Gallery.[17]The city is also known for theEdinburgh International Festivaland theFringe, the latter being the world's largest annual international arts festival. Historic sites in Edinburgh includeEdinburgh Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the churches ofSt. Giles,Greyfriarsand theCanongate, and the extensive Georgian New Town built in the 18th/19th centuries. Edinburgh'sOld TownandNew Towntogether are listed as aUNESCOWorld Heritage Site,[18]which has been managed byEdinburgh World Heritagesince 1999. The city's historical and cultural attractions have made it the UK's second-most visited tourist destination, attracting 4.9 million visits, including 2.4 million from overseas in 2018.[19][20]

Edinburgh is governed by theCity of Edinburgh Council, a unitary authority. The City of Edinburgh council area had an estimated population of 514,990 in mid-2021,[9]and includes outlying towns and villages which are not part of Edinburgh proper. The city is in theLothianregion and was historically part of theshireofMidlothian(also called Edinburghshire).

Etymology

[edit]"Edin", the root of the city's name, derives fromEidyn, the name for the region inCumbric, theBrittonicCelticlanguage formerly spoken there. The name's meaning is unknown.[21]The district of Eidyn was centred on the stronghold of Din Eidyn, thedunorhillfortof Eidyn.[21]This stronghold is believed to have been located atCastle Rock,[citation needed]now the site ofEdinburgh Castle. A siege of Din Eidyn byOswald, king of theAnglesofNorthumbriain 638 marked the beginning of three centuries of Germanic influence in south east Scotland that laid the foundations for the development ofScots, before the town was ultimately subsumed in 954 by the kingdom known to the English as Scotland.[22]As the language shifted from Cumbric toNorthumbrian Old Englishand thenScots, the Brittonicdinin Din Eidyn was replaced byburh, producingEdinburgh. InScottish Gaelicdinbecomesdùn, producing modernDùn Èideann.[21][23]

Nicknames

[edit]

The city is affectionately nicknamedAuld Reekie,[24][25]Scots forOld Smoky, for the views from the country of the smoke-covered Old Town. A note in a collection of the works of the poet,Allan Ramsay, explains, "Auld Reeky...A name the country people give Edinburgh, from the cloud of smoke or reek that is always impending over it."[26]InWalter Scott's 1820 novelThe Abbot, a character observes that "yonder stands Auld Reekie—you may see the smoke hover over her at twenty miles' distance".[27]In 1898,Thomas Carlylecomments on the phenomenon: "Smoke cloud hangs over old Edinburgh, for, ever sinceAeneas Silvius's time and earlier, the people have the art, very strange to Aeneas, of burning a certain sort of black stones, and Edinburgh with its chimneys is called 'Auld Reekie' by the country people".[28]The 19th-century historianRobert Chambersasserted that the sobriquet could not be traced before the reign ofCharles IIin the late 17th century. He attributed the name to aFifelaird, Durham of Largo, who regulated the bedtime of his children by the smoke rising above Edinburgh from the fires of the tenements. "It's time now bairns, to tak' the beuks, and gang to our beds, for yonder's Auld Reekie, I see, putting on her nicht -cap!".[29]

Edinburgh has been popularly called theAthens of the Northsince the early 19th century.[30]References to Athens, such asAthens of BritainandModern Athens, had been made as early as the 1760s. The similarities were seen to be topographical but also intellectual. Edinburgh's Castle Rock reminded returninggrand touristsof theAthenianAcropolis, as did aspects of theneoclassical architectureand layout ofNew Town.[30]Both cities had flatter, fertile agricultural land sloping down to aportseveral miles away (respectively,LeithandPiraeus). Intellectually, theScottish Enlightenment, with itshumanistandrationalistoutlook, was influenced byAncient Greek philosophy.[31]In 1822, artistHugh William Williamsorganized an exhibition that showed his paintings of Athens alongside views of Edinburgh, and the idea of a direct parallel between both cities quickly caught the popular imagination.[32]When plans were drawn up in the early 19th century to architecturally developCalton Hill, the design of theNational Monumentdirectly copied Athens'Parthenon.[33]Tom Stoppard's character Archie ofJumperssaid, perhaps playing onReykjavíkmeaning "smoky bay", that the "Reykjavík of the South" would be more appropriate.[34]

The city has also been known by severalLatin names, such asEdinburgum, while the adjectival formsEdinburgensisandEdinensisare used in educational and scientific contexts.[35][36]

Edinais a late 18th-century poetical form used by the Scots poetsRobert FergussonandRobert Burns. "Embra" or "Embro" are colloquialisms from the same time,[37]as inRobert Garioch'sEmbro to the Ploy.[38]

Ben Jonsondescribed it as "Britaine's other eye",[39]and Sir Walter Scott referred to it as "yon Empress of the North".[40]Robert Louis Stevenson, also a son of the city, wrote that Edinburgh "is what Paris ought to be".[41]

History

[edit]Early history

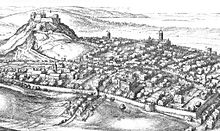

[edit]

The earliest known human habitation in the Edinburgh area was atCramond, where evidence was found of aMesolithiccamp site dated to c. 8500 BC.[42]Traces of laterBronze AgeandIron Agesettlements have been found on Castle Rock,Arthur's Seat,Craiglockhart Hilland thePentland Hills.[43]

When theRomansarrived in Lothian at the end of the 1st century AD, they found aBrittonicCeltic tribe whose name they recorded as theVotadini.[44]The Votadini transitioned into theGododdinkingdom in theEarly Middle Ages, with Eidyn serving as one of the kingdom's districts. During this period, the Castle Rock site, thought to have been the stronghold of Din Eidyn, emerged as the kingdom's major centre.[45]The medieval poemY Gododdindescribes a war band from across the Brittonic world who gathered in Eidyn before a fateful raid; this may describe a historical event around AD 600.[46][47][48]

In 638, the Gododdin stronghold was besieged by forces loyal toKing OswaldofNorthumbria, and around this time control of Lothian passed to theAngles. Their influence continued for the next three centuries until around 950, when, during the reign ofIndulf, son ofConstantine II, the "burh" (fortress), named in the 10th-centuryPictish Chronicleasoppidum Eden,[49]was abandoned to the Scots. It thenceforth remained, for the most part, under their jurisdiction.[50]

Theroyal burghwas founded byKing David Iin the early 12th century on land belonging to the Crown, though the date of its charter is unknown.[51]The first documentary evidence of the medievalburghis aroyal charter,c. 1124–1127, by King David I granting atoftinburgo meo de Edenesburgto thePriory of Dunfermline.[52]Theshireof Edinburgh seems to have also been created in the reign of David I, possibly covering all of Lothian at first, but by 1305 the eastern and western parts of Lothian had becomeHaddingtonshireandLinlithgowshire, leaving Edinburgh as the county town of a shire covering the central part of Lothian, which was called Edinburghshire orMidlothian(the latter name being an informal, but commonly used, alternative until the county's name was legally changed in 1947).[53][54]

Edinburgh was largely under English control from 1291 to 1314 and from 1333 to 1341, during theWars of Scottish Independence. When theEnglish invaded Scotland in 1298,Edward I of Englandchose not to enter Edinburgh but passed by it with his army.[55]

In the middle of the 14th century, the French chroniclerJean Froissartdescribed it as the capital of Scotland (c. 1365), andJames III(1451–88) referred to it in the 15th century as "the principal burgh of our kingdom".[56]In 1482 James III "granted and perpetually confirmed to the said Provost, Bailies, Clerk, Council, and Community, and their successors, the office ofSheriffwithin the Burgh for ever, to be exercised by the Provost for the time as Sheriff, and by the Bailies for the time as Sheriffsdepute conjunctly and severally; with full power to hold Courts, to punish transgressors not only by banishment but by death, to appoint officers of Court, and to do everything else appertaining to the office of Sheriff; as also to apply to their own proper use the fines and escheats arising out of the exercise of the said office."[57]Despite beingburnt by the Englishin 1544, Edinburgh continued to develop and grow,[58]and was at the centre of events in the 16th-centuryScottish Reformation[59]and 17th-centuryWars of the Covenant.[60]In 1582, Edinburgh's town council was given aroyal charterby KingJames VIpermitting the establishment of a university;[61]founded asTounis College(Town's College), the institution developed into theUniversity of Edinburgh, which contributed to Edinburgh's central intellectual role in subsequent centuries.[62]

17th century

[edit]

In 1603, KingJames VIof Scotland succeeded to the English throne, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England in apersonal unionknown as theUnion of the Crowns, though Scotland remained, in all other respects, a separate kingdom.[63]In 1638,King Charles I'sattempt to introduceAnglicanchurch forms in Scotland encountered stiffPresbyterianopposition culminating in the conflicts of theWars of the Three Kingdoms.[64]Subsequent Scottish support forCharles Stuart's restoration to the throne of England resulted in Edinburgh's occupation byOliver Cromwell'sCommonwealth of Englandforces – theNew Model Army– in 1650.[65]

In the 17th century, Edinburgh's boundaries were still defined by the city's defensivetown walls. As a result, the city's growing population was accommodated by increasing the height of the houses. Buildings of 11 storeys or more were common,[66]and have been described as forerunners of the modern-day skyscraper.[67][68]Most of these old structures were replaced by the predominantlyVictorianbuildings seen in today's Old Town. In 1611 an act of parliament created theHigh Constables of Edinburghto keep order in the city, thought to be the oldest statutory police force in the world.[69]

18th century

[edit]

Following theTreaty of Unionin 1706, the Parliaments of England and Scotland passedActs of Unionin 1706 and 1707 respectively, uniting the two kingdoms in theKingdom of Great Britaineffective from 1 May 1707.[70]As a consequence, theParliament of Scotlandmerged with theParliament of Englandto form theParliament of Great Britain, which sat atWestminsterin London. The Union was opposed by many Scots, resulting in riots in the city.[71]

By the first half of the 18th century, Edinburgh was described as one of Europe's most densely populated, overcrowded and unsanitary towns.[72][73]Visitors were struck by the fact that the social classes shared the same urban space, even inhabiting the sametenementbuildings; although here a form of social segregation did prevail, whereby shopkeepers and tradesmen tended to occupy the cheaper-to-rent cellars and garrets, while the more well-to-do professional classes occupied the more expensive middle storeys.[74]

During theJacobite rising of 1745, Edinburgh was briefly occupied by the Jacobite "Highland Army" before its march into England.[75]After its eventual defeat atCulloden, there followed a period of reprisals and pacification, largely directed at the rebelliousclans.[76]In Edinburgh, the Town Council, keen to emulate London by initiating city improvements and expansion to the north of the castle,[77]reaffirmed its belief in the Union and loyalty to theHanoverianmonarchGeorge IIIby its choice of names for the streets of the New Town: for example,RoseStreet andThistleStreet; and for the royal family,George Street,Queen Street, Hanover Street, Frederick Street andPrinces Street(in honour of George's two sons).[78]The consistently geometric layout of the plan for the extension of Edinburgh was the result of a major competition in urban planning staged by the Town Council in 1766.[79]

In the second half of the century, the city was at the heart of theScottish Enlightenment,[80]when thinkers like David Hume, Adam Smith,James HuttonandJoseph Blackwere familiar figures in its streets. Edinburgh became a major intellectual centre, earning it the nickname "Athens of the North" because of its manyneo-classicalbuildings and reputation for learning, recalling ancient Athens.[81]In the 18th-century novelThe Expedition of Humphry ClinkerbyTobias Smollettone character describes Edinburgh as a "hotbed of genius".[82]Edinburgh was also a major centre for the Scottish book trade. The highly successful London booksellerAndrew Millarwas apprenticed there to James McEuen.[83]

From the 1770s onwards, the professional and business classes gradually deserted the Old Town in favour of the more elegant "one-family" residences of the New Town, a migration that changed the city's social character. According to the foremost historian of this development, "Unity of social feeling was one of the most valuable heritages of old Edinburgh, and its disappearance was widely and properly lamented."[84]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]

Despite an enduring myth to the contrary,[85]Edinburgh became an industrial centre[86]with its traditional industries of printing, brewing and distilling continuing to grow in the 19th century and joined by new industries such asrubber works,engineering worksand others. By 1821, Edinburgh had been overtaken byGlasgowas Scotland's largest city.[87]The city centre between Princes Street and George Street became a major commercial and shopping district, a development partly stimulated by the arrival of railways in the 1840s. The Old Town became an increasingly dilapidated, overcrowded slum with high mortality rates.[88]Improvements carried out under Lord ProvostWilliam Chambersin the 1860s began the transformation of the area into the predominantlyVictorianOld Town seen today.[89]More improvements followed in the early 20th century as a result of the work ofPatrick Geddes,[90]but relative economic stagnation during the two world wars and beyond saw the Old Town deteriorate further before majorslum clearancein the 1960s and 1970s began to reverse the process. University building developments which transformed theGeorge Squareand Potterrow areas proved highly controversial.[91]

Since the 1990s a new "financial district", including theEdinburgh International Conference Centre, has grown mainly on demolished railway property to the west of the castle, stretching intoFountainbridge, a run-down 19th-century industrial suburb which has undergone radical change since the 1980s with the demise of industrial and brewery premises. This ongoing development has enabled Edinburgh to maintain its place as the United Kingdom's second largest financial and administrative centre after London.[92][93]Financial services now account for a third of all commercial office space in the city.[94]The development ofEdinburgh Park, a new business and technology park covering 38 acres (15 ha), 4 mi (6 km) west of the city centre, has also contributed to the District Council's strategy for the city's major economic regeneration.[94]

In 1998, theScotland Act, which came into force the following year, established adevolvedScottish Parliament and Scottish Executive (renamed the Scottish Government since September 2007[95]). Both based in Edinburgh, they are responsible for governing Scotland whilereserved matterssuch as defence, foreign affairs and some elements of income tax remain the responsibility of theParliament of the United Kingdomin London.[96]

21st century

[edit]In 2022, Edinburgh was affected by the2022 Scotland bin strikes.[97]In 2023, Edinburgh became the first capital city in Europe to sign the globalPlant Based Treaty, which was introduced atCOP26in 2021 in Glasgow.[98]Green Party councillor Steve Burgess introduced the treaty. The Scottish Countryside Alliance and other farming groups called the treaty "anti-farming".[99]

Geography

[edit]Location

[edit]Situated in Scotland'sCentral Belt, Edinburgh lies on the southern shore of the Firth of Forth. The city centre is2+1⁄2mi (4.0 km) southwest of the shoreline ofLeithand 26 mi (42 km) inland, as the crow flies, from the east coast of Scotland and theNorth SeaatDunbar.[100]While the early burgh grew up near the prominent Castle Rock, the modern city is often said to be built onseven hills, namelyCalton Hill,Corstorphine Hill, Craiglockhart Hill,Braid Hill,Blackford Hill, Arthur's Seat and the Castle Rock,[101]giving rise to allusions to theseven hills of Rome.[102]

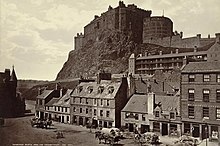

Cityscape

[edit]Occupying a narrow gap between the Firth of Forth to the north and thePentland Hillsand their outrunners to the south, the city sprawls over a landscape which is the product of early volcanic activity and later periods of intensive glaciation.[103]: 64–65 Igneous activity between 350 and 400 million years ago, coupled withfaulting, led to the creation of toughbasaltvolcanic plugs, which predominate over much of the area.[103]: 64–65 One such example is the Castle Rock which forced the advancing ice sheet to divide, sheltering the softer rock and forming a 1 mi-long (1.6 km) tail of material to the east, thus creating a distinctivecrag and tailformation.[103]: 64–65 Glacial erosion on the north side of the crag gouged a deep valley later filled by the now drainedNor Loch. These features, along with another hollow on the rock's south side, formed an ideal natural strongpoint upon which Edinburgh Castle was built.[103]: 64–65 Similarly, Arthur's Seat is the remains of a volcano dating from theCarboniferous period, which was eroded by a glacier moving west to east during the ice age.[103]: 64–65 Erosive action such aspluckingandabrasionexposed the rocky crags to the west before leaving a tail of deposited glacial material swept to the east.[104]This process formed the distinctiveSalisbury Crags, a series ofteschenitecliffs between Arthur's Seat and the location of the early burgh.[105]The residential areas ofMarchmontandBruntsfieldare built along a series ofdrumlinridges south of the city centre, which weredepositedas the glacier receded.[103]: 64–65

Other prominent landforms such as Calton Hill and Corstorphine Hill are also products of glacial erosion.[103]: 64–65 The Braid Hills and Blackford Hill are a series of small summits to the south of the city centre that command expansive views looking northwards over the urban area to the Firth of Forth.[103]: 64–65

Edinburgh is drained by the river named theWater of Leith, which rises at the Colzium Springs in the Pentland Hills and runs for 18 miles (29 km) through the south and west of the city, emptying into the Firth of Forth at Leith.[106]The nearest the river gets to the city centre is atDean Villageon the north-western edge of the New Town, where a deep gorge is spanned byThomas Telford'sDean Bridge, built in 1832 for the road toQueensferry. TheWater of Leith Walkwayis a mixed-usetrailthat follows the course of the river for 19.6 km (12.2 mi) from Balerno to Leith.[107]

Excepting the shoreline of the Firth of Forth, Edinburgh is encircled by agreen belt, designated in 1957, which stretches fromDalmenyin the west toPrestongrangein the east.[108]With an average width of 3.2 km (2 mi) the principal objectives of the green belt were to contain the outward expansion of the city and to prevent the agglomeration of urban areas.[108]Expansion affecting the green belt is strictly controlled but developments such asEdinburgh Airportand theRoyal Highland ShowgroundatInglistonlie within the zone.[108]Similarly, suburbs such asJuniper Greenand Balerno are situated on green belt land.[108]One feature of the Edinburgh green belt is the inclusion of parcels of land within the city which are designated green belt, even though they do not connect with the peripheral ring. Examples of these independent wedges of green belt includeHolyrood Parkand Corstorphine Hill.[108]

Areas

[edit]

Early settlements

[edit]Edinburgh includes former towns and villages that retain much of their original character as settlements in existence before they were absorbed into the expanding city of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[109]Many areas, such asDalry, contain residences that are multi-occupancy buildings known astenements, although the more southern and western parts of the city have traditionally been less built-up with a greater number of detached and semi-detached villas.[110]

The historic centre of Edinburgh is divided in two by the broad green swathe ofPrinces Street Gardens. To the south, the view is dominated by Edinburgh Castle, built high on Castle Rock, and the long sweep of the Old Town descending towards Holyrood Palace. To the north lie Princes Street and the New Town.

TheWest Endincludes the financial district, with insurance and banking offices as well as the Edinburgh International Conference Centre.

Old and New Towns

[edit]Edinburgh's Old and New Towns were listed as a UNESCOWorld Heritage Sitein 1995 in recognition of the unique character of the Old Town with its medieval street layout and the planned Georgian New Town, including the adjoining Dean Village and Calton Hill areas. There are over 4,500listed buildingswithin the city,[18]a higher proportion relative to area than any other city in the United Kingdom.

The castle is perched on top of a rocky crag (the remnant of an extinct volcano) and theRoyal Mileruns down the crest of a ridge from it terminating at Holyrood Palace. Minor streets (called closes orwynds) lie on either side of the main spine forming a herringbone pattern.[111]Due to space restrictions imposed by the narrowness of this landform, the Old Town became home to some of the earliest "high rise" residential buildings. Multi-storey dwellings known aslandswere the norm from the 16th century onwards with ten and eleven storeys being typical and one even reaching fourteen or fifteen storeys.[112]Numerous vaults below street level were inhabited to accommodate the influx of incomers, particularlyIrish immigrants, during theIndustrial Revolution. The street has several fine public buildings such as St Giles' Cathedral, theCity Chambersand theLaw Courts. Other places of historical interest nearby areGreyfriars KirkyardandMary King's Close. TheGrassmarket, running deep below the castle is connected by the steep double terraced Victoria Street. The street layout is typical of the old quarters of many Northern European cities.

The New Town was an 18th-century solution to the problem of an increasingly crowded city which had been confined to the ridge sloping down from the castle. In 1766 a competition to design a "New Town" was won byJames Craig, a 27-year-old architect.[113]The plan was a rigid, ordered grid, which fitted in well withEnlightenmentideas of rationality. The principal street was to beGeorge Street, running along the natural ridge to the north of what became known as the "Old Town". To either side of it are two other main streets: Princes Street and Queen Street. Princes Street has become Edinburgh's main shopping street and now has few of itsGeorgianbuildings in their original state. The three main streets are connected by a series of streets running perpendicular to them. The east and west ends of George Street are terminated bySt Andrew SquareandCharlotte Squarerespectively. The latter, designed byRobert Adam, influenced the architectural style of the New Town into the early 19th century.[114]Bute House, the official residence of theFirst Minister of Scotland, is on the north side of Charlotte Square.[115]

The hollow between the Old and New Towns was formerly theNor Loch, which was created for the town's defence but came to be used by the inhabitants for dumping theirsewage. It was drained by the 1820s as part of the city's northward expansion. Craig's original plan included an ornamental canal on the site of the loch,[78]but this idea was abandoned.[116]Soil excavated while laying the foundations of buildings in the New Town was dumped on the site of thelochto create the slope connecting the Old and New Towns known asThe Mound.

In the middle of the 19th century theNational Gallery of ScotlandandRoyal Scottish Academy Buildingwere built on The Mound, and tunnels for the railway line betweenHaymarketandWaverleystations were driven through it.

Southside

[edit]The Southside is a residential part of the city, which includes the districts ofSt Leonards,Marchmont,Morningside,Newington,Sciennes,the GrangeandBlackford. The Southside is broadly analogous to the area covered formerly by theBurgh Muir, and was developed as a residential area after the opening of theSouth Bridgein the 1780s. The Southside is particularly popular with families (many state and private schools are here), young professionals and students (the central University of Edinburgh campus is based aroundGeorge Squarejust north of Marchmont andthe Meadows), andNapier University(with major campuses around Merchiston and Morningside). The area is also well provided with hotel and "bed and breakfast" accommodation for visiting festival-goers. These districts often feature in works of fiction. For example,Church Hillin Morningside, was the home ofMuriel Spark's Miss Jean Brodie,[117]andIan Rankin'sInspector Rebuslives in Marchmont and works in St Leonards.[118]

Leith

[edit]

Leithwas historically the port of Edinburgh, an arrangement of unknown date that was confirmed by the royal charter Robert the Bruce granted to the city in 1329.[119]The port developed a separate identity from Edinburgh, which to some extent it still retains, and it was a matter of great resentment when the two burghs merged in 1920 into the City of Edinburgh.[120]Even today the parliamentary seat is known as "Edinburgh North and Leith". The loss of traditional industries and commerce (thelast shipyardclosed in 1983) resulted in economic decline.[121]The Edinburgh Waterfront development has transformed old dockland areas from Leith to Granton into residential areas with shopping and leisure facilities and helped rejuvenate the area. With the redevelopment, Edinburgh has gained the business of cruise liner companies which now provide cruises to Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, and the Netherlands.

The coastal suburb ofPortobellois characterised by Georgian villas, Victorian tenements, a beach andpromenadeand cafés, bars, restaurants and independent shops. There are rowing and sailing clubs, a restored Victorian swimming pool, andVictorian Turkish baths.

Urban area

[edit]Theurban areaof Edinburgh is almost entirely within theCity of Edinburgh Councilboundary, merging withMusselburghin East Lothian. Towns within easy reach of the city boundary includeInverkeithing,Haddington,Tranent,Prestonpans,Dalkeith,Bonnyrigg,Loanhead,Penicuik,Broxburn,LivingstonandDunfermline. Edinburgh lies at the heart of the Edinburgh & South East Scotland City region with a population in 2014 of 1,339,380.[122][123]

Climate

[edit]Like most of Scotland, Edinburgh has a cooltemperatemaritime climate(Cfb) which, despite its northerly latitude, is milder than places which lie at similar latitudes such asMoscowandLabrador.[124]The city's proximity to the sea mitigates any large variations in temperature or extremes of climate. Winter daytime temperatures rarely fall below freezing while summer temperatures are moderate, rarely exceeding 22 °C (72 °F).[124]The highest temperature recorded in the city was 31.6 °C (88.9 °F) on 25 July 2019[124]at Gogarbank, beating the previous record of 31 °C (88 °F) on 4 August 1975 at Edinburgh Airport.[125]The lowest temperature recorded in recent years was −14.6 °C (5.7 °F) during December 2010 at Gogarbank.[126]

Given Edinburgh's position between the coast and hills, it is renowned as "the windy city", with the prevailing wind direction coming from the south-west, which is often associated with warm, unstable air from theNorth Atlantic Currentthat can give rise to rainfall – although considerably less than cities to the west, such as Glasgow.[124]Rainfall is distributed fairly evenly throughout the year.[124]Winds from an easterly direction are usually drier but considerably colder, and may be accompanied byhaar, a persistent coastal fog. Vigorous Atlantic depressions, known asEuropean windstorms, can affect the city between October and April.[124]

Located slightly north of the city centre, the weather station at theRoyal Botanic Garden Edinburgh(RBGE) has been an official weather station for theMet Officesince 1956. The Met Office operates its own weather station at Gogarbank on the city's western outskirts, nearEdinburgh Airport.[127]This slightly inland station has a slightly wider temperature span between seasons, is cloudier and somewhat wetter, but differences are minor.

Temperature and rainfall records have been kept at the Royal Observatory since 1764.[128]

| Climate data for Edinburgh (RBGE),[a]elevation: 23 m (75 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1960–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.8 (73.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

27.8 (82.0) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.4 (88.5) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

8.0 (46.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

9.9 (49.8) |

7.3 (45.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.5 (40.1) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.5 (40.1) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) |

1.7 (35.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.7 (49.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.1 (43.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15.5 (4.1) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−6.1 (21.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

1.1 (34.0) |

4.4 (39.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.7 (25.3) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 64.7 (2.55) |

53.1 (2.09) |

48.5 (1.91) |

40.8 (1.61) |

47.6 (1.87) |

66.2 (2.61) |

72.1 (2.84) |

71.6 (2.82) |

54.9 (2.16) |

75.7 (2.98) |

65.3 (2.57) |

67.4 (2.65) |

727.7 (28.65) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.4 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 8.6 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 11.5 | 10.4 | 9.9 | 11.7 | 11.7 | 12.3 | 128.3 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 55.2 | 82.2 | 117.3 | 157.3 | 194.7 | 161.8 | 169.9 | 160.0 | 130.1 | 99.4 | 72.1 | 49.2 | 1,449.1 |

| Averageultraviolet index | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Source:Met Office,[129]KNMI[130]and Weather Atlas[131] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Edinburgh (Gogarbank),[b]elevation: 57 m (187 ft), 1991–2020 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

4.6 (40.3) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

13.4 (56.1) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

9.8 (49.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

1.6 (34.9) |

2.7 (36.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.0 (51.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

6.5 (43.7) |

3.6 (38.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

| Averageprecipitationmm (inches) | 73.0 (2.87) |

61.1 (2.41) |

52.5 (2.07) |

45.9 (1.81) |

50.2 (1.98) |

68.8 (2.71) |

71.9 (2.83) |

74.7 (2.94) |

55.2 (2.17) |

82.7 (3.26) |

73.7 (2.90) |

74.9 (2.95) |

784.3 (30.88) |

| Average precipitation days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 13.3 | 10.7 | 10.3 | 9.2 | 10.8 | 11.1 | 11.4 | 11.2 | 10.5 | 13.0 | 12.9 | 13.1 | 137.4 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 47.4 | 77.5 | 111.0 | 147.7 | 189.5 | 159.4 | 160.9 | 145.7 | 125.5 | 94.1 | 66.9 | 37.8 | 1,363.4 |

| Source:Met Office[132] | |||||||||||||

Demography

[edit]Current

[edit]

The most recent official population estimates (2020) are 506,520 for the locality (includesCurrie),[8]530,990 for the Edinburgh settlement (includesMusselburgh).[8]

Edinburgh has a high proportion of young adults, with 19.5% of the population in their 20s (exceeded only by Aberdeen) and 15.2% in their 30s which is the highest in Scotland. The proportion of Edinburgh's population born in the UK fell from 92% to 84% between 2001 and 2011, while the proportion of White Scottish-born fell from 78% to 70%. Of those Edinburgh residents born in the UK, 335,000 or 83% were born in Scotland, with 58,000 or 14% being born in England.[133]

| Ethnic Group | 1991[134][135] | 2001[136][137] | 2011[136][137] | 2022[138] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 409,044 | 97.64% | 430,369 | 95.9% | 437,167 | 91.7% | 436,742 | 84.9% |

| White:Scottish | – | – | 354,053 | 78.9% | 334,987 | 70.2% | 298,533 | 58.0% |

| White:Other British | – | – | 51,407 | 11.4% | 56,132 | 11.7% | 69,829 | 13.6% |

| White:Irish | 5,518 | 1.31% | 6,470 | 1.4% | 8,603 | 1.8% | 10,326 | 2.0% |

| White:Gypsy/Traveller[note 1] | – | – | – | – | 388 | – | 256 | – |

| White:Polish[note 1] | – | – | – | – | 12,820 | 2.68% | 16,351 | 3.18% |

| White:Other | – | – | 18,439 | 4.1% | 24,237 | 5.1% | 41,449 | 8.1% |

| Asian,Asian ScottishorAsian British: Total | 6,979 | 1.66% | 11,600 | 2.5% | 26,264 | 5.5% | 44,070 | 8.6% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British:Indian | 1,176 | 0.28% | 2,384 | 0.53% | 6,470 | 1.35% | 12,414 | 2.41% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British:Pakistani | 2,625 | 0.62% | 3,928 | 0.87% | 5,858 | 1.22% | 7,454 | 1.45% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British:Bangladeshi | 328 | – | 636 | 0.14% | 1,277 | 0.26% | 2,685 | 0.52% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British:Chinese | 1,940 | 0.46% | 3,532 | 0.78% | 8,076 | 1.69% | 15,076 | 2.93% |

| Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British:Asian Other | 910 | 0.21% | 1,201 | 0.26% | 4,583 | 0.96% | 6,441 | 1.25% |

| Black,Black ScottishorBlack British[note 2] | 1,171 | 0.3% | 1,577 | 0.3% | 5,505 | 1.2% | 10,881 | 2.1% |

| African: Total | 603 | - | 1,285 | 0.2% | 4,474 | 0.9% | 9,462 | 1.84% |

| African:African,African ScottishorAfrican British | 603 | – | 1,285 | 0.2% | 4,364 | 0.91% | 809 | 0.16% |

| African:Other African | – | – | – | – | 110 | – | 8,653 | 1.68% |

| CaribbeanorBlack: Total | 568 | – | 292 | – | 1,031 | 0.2% | 1,419 | 0.3% |

| Caribbean | 175 | – | 292 | – | 505 | 0.1% | 477 | 0.1% |

| Black | – | – | – | – | 403 | – | 80 | – |

| Caribbean or Black:Other | 393 | – | – | – | 123 | – | 862 | 0.17% |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups: Total | – | – | 2,776 | 0.6% | 4,087 | 0.8% | 12,882 | 2.5% |

| Other: Total | 1,720 | 0.41% | 2,047 | 0.45% | 3,603 | 0.8% | 9,966 | 1.9% |

| Other:Arab[note 1] | – | – | – | – | 2,500 | 0.52% | 4,119 | 0.8% |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | 1,720 | 0.41% | 2,047 | 0.45% | 1,103 | 0.23% | 5,849 | 1.14% |

| Total: | 418,914 | 100% | 448,624 | 100% | 476,626 | 100% | 514,543 | 100% |

Some 16,000 people or 3.2% of the city's population are ofPolishdescent. 77,800 people or 15.1% of Edinburgh's population class themselves as Non-White which is an increase from 8.2% in 2011 and 4% in 2001. Of the Non-White population, the largest group by far areAsian, totalling about 44 thousand people. Within the Asian population, people ofChinesedescent are now the largest sub-group, with 15,076 people, amounting to about 2.9% of the city's total population. The city's population ofIndiandescent amounts to 12,414 (2.4% of the total population), while there are some 7,454 ofPakistanidescent (1.5% of the total population). Although they account for only 2,685 people or 0.5% of the city's population, Edinburgh has the highest number and proportion of people ofBangladeshidescent in Scotland. Close to 12,000 people were born in African countries (2.3% of the total population) and over 13,000 in the Americas. With the notable exception of Inner London, Edinburgh has a higher number of people born in the United States (over 6,500) than any other city in the UK.[138]

The proportion of people residing in Edinburgh born outside the UK was 23.5% in 2022, compared with 15.9% in 2011 and 8.3% in 2001. Below are the largest overseas-born groups in Edinburgh according to the 2022 census, alongside the two previous censuses.

| Place of birth | 2022[139] | 2011[140] | 2001[141] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13,842 | 11,651 | 416 | |

| 9,445 | 4,888 | 1,733 | |

| 8,229 | 4,188 | 978 | |

| 6,539 | 3,715 | 2,184 | |

| 4,885 | 1,716 | 1,257 | |

| 4,837 | 2,011 | 1,058 | |

| 4,774 | 4,743 | 3,324 | |

| 3,843 | 3,526 | 2,760 | |

| 3,556 | 1,622 | 1,416 | |

| 3,220 | 2,472 | 1,663 | |

| 2,978 | 1,186 | 231 | |

| 2,973 | 2,039 | 1,412 | |

| 2,464 | 1,824 | 1,331 | |

| 2,377 | 992 | 575 | |

| 2,189 | 2,086 | 2,012 | |

| 2,079 | 1,760 | 1,332 | |

| Overall – all overseas-born | 120,978 | 75,698 | 37,420 |

Historical

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 82,560 | — |

| 1811 | 102,987 | +24.7% |

| 1821 | 138,235 | +34.2% |

| 1831 | 161,909 | +17.1% |

| 1841 | 166,450 | +2.8% |

| 1851 | 193,929 | +16.5% |

| 1901 | 303,638 | +56.6% |

| 1911 | 320,318 | +5.5% |

| 1921 | 420,264 | +31.2% |

| 1931 | 439,010 | +4.5% |

| 1951 | 466,761 | +6.3% |

| Source: [142] |

||

A census by the Edinburgh presbytery in 1592 recorded a population of 8,003 adults spread equally north and south of the High Street which runs along the spine of the ridge sloping down from the Castle.[143]In the 18th and 19th centuries, the population expanded rapidly, rising from 49,000 in 1751 to 136,000 in 1831, primarily due to migration from rural areas.[103]: 9 As the population grew, problems of overcrowding in the Old Town, particularly in the crampedtenementsthat lined the present day Royal Mile and theCowgate, were exacerbated.[103]: 9 Poor sanitary arrangements resulted in a high incidence of disease,[103]: 9 with outbreaks ofcholeraoccurring in 1832, 1848 and 1866.[144]

The construction of the New Town from 1767 onwards witnessed the migration of the professional and business classes from the difficult living conditions in the Old Town to the lower density, higher quality surroundings taking shape on land to the north.[145]Expansion southwards from the Old Town saw more tenements being built in the 19th century, giving rise toVictoriansuburbs such asDalry, Newington, Marchmont and Bruntsfield.[145]

Early 20th-century population growth coincided with lower-density suburban development. As the city expanded to the south and west, detached and semi-detached villas with large gardens replaced tenements as the predominant building style. Nonetheless, the 2001 census revealed that over 55% of Edinburgh's population were still living in tenements or blocks of flats, a figure in line with other Scottish cities, but much higher than other British cities, and even central London.[146]

From the early to mid 20th century, the growth in population, together with slum clearance in the Old Town and other areas, such asDumbiedykes,Leith, andFountainbridge, led to the creation of new estates such asStenhouseandSaughton,CraigmillarandNiddrie,PiltonandMuirhouse,Piershill, andSighthill.[147]

Religion

[edit]

In 2018, theChurch of Scotlandhad 20,956 members in 71 congregations in thePresbytery of Edinburgh.[149]Its most prominent church is St Giles' on the Royal Mile, first dedicated in 1243 but believed to date from before the 12th century.[150]Saint Gilesis historically the patron saint of Edinburgh.[151]St Cuthbert's, situated at the west end of Princes Street Gardens in the shadow of Edinburgh Castle and St Giles' can lay claim to being the oldest Christian sites in the city,[152]though the present St Cuthbert's, designed byHippolyte Blanc, was dedicated in 1894.[153]

Other Church of Scotland churches includeGreyfriars Kirk, theCanongate Kirk,The New Town Churchand theBarclay Church. TheChurch of Scotland Officesare in Edinburgh,[154]as is theAssembly Hallwhere the annualGeneral Assemblyis held.[155]

TheRoman Catholic Archdiocese of St Andrews and Edinburghhas 27 parishes across the city.[156]TheArchbishop of St Andrews and Edinburghhas his official residence inGreenhill,[157]the diocesan offices are in nearbyMarchmont,[158]and its cathedral isSt Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh. TheDiocese of Edinburghof theScottish Episcopal Churchhas over 50 churches, half of them in the city.[159]Its centre is the late 19th-centuryGothicstyleSt Mary's Cathedralin the West End's Palmerston Place.[160]Orthodox Christianity is represented by Pan,RomanianandRussianOrthodox churches, includingSt Andrew's Orthodox Church, part of theGreek Orthodox Archdiocese of Thyateira and Great Britain.[161]There are several independent churches in the city, bothCatholicandProtestant, includingCharlotte Chapel,Carrubbers Christian Centre,Bellevue ChapelandSacred Heart.[162]There are also churches belonging toQuakers,Christadelphians,[163]Seventh-day Adventists,Church of Christ, Scientist,The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints(LDS Church) andElim Pentecostal Church.

Muslims have several places of worship across the city.Edinburgh Central Mosque, the largest Islamic place of worship, is located in Potterrow on the city's Southside, near Bristo Square. Construction was largely financed by a gift from KingFahd of Saudi Arabia[164]and was completed in 1998.[165]There is also anAhmadiyyaMuslim community.[166]

The first recorded presence of aJewish communityin Edinburgh dates back to the late 18th century.[167]Edinburgh'sOrthodoxsynagogue, opened in 1932, is in Salisbury Road and can accommodate a congregation of 2000. ALiberal Jewish congregationalso meets in the city.

ASikhgurdwaraand aHindumandirare located in Leith.[168][169]The city also has aBrahma Kumariscentre in the Polwarth area.[170]

The Edinburgh Buddhist Centre, run by theTriratna Buddhist Community, formerly situated in Melville Terrace, now runs sessions at the Healthy Life Centre, Bread Street.[171]Other Buddhist traditions are represented by groups which meet in the capital: the Community of Interbeing (followers ofThich Nhat Hanh),Rigpa, Samye Dzong,Theravadin,Pure LandandShambala. There is aSōtō ZenPriory in Portobello[172]and a Theravadin Thai Buddhist Monastery in Slateford Road.[173]

Edinburgh is home to aBaháʼícommunity,[174]and aTheosophical Societymeets in Great King Street.[175]

Edinburgh has an Inter-Faith Association.[176]

Edinburgh has over 39graveyards and cemeteries, many of which are listed and of historical character, including several former church burial grounds.[177]Examples includeOld Calton Burial Ground,Greyfriars KirkyardandDean Cemetery.[178][179][180]

Economy

[edit]

Edinburgh has the strongest economy of any city in the United Kingdom outside London and the highest percentage of professionals in the UK with 43% of the population holding a degree-level or professional qualification.[181]According to the Centre for International Competitiveness, it is the most competitive large city in the United Kingdom.[182]It also has the highestgross value addedper employee of any city in the UK outside London, measuring £57,594 in 2010.[183]It was named European Best Large City of the Future for Foreign Direct Investment and Best Large City for Foreign Direct Investment Strategy in theFinancial Timesmagazine in 2012.[184]

As the centre ofScotland's governmentandlegal system, the public sector plays a central role in Edinburgh's economy. Many departments of the Scottish Government are in the city, including the headquarters of the government atSt Andrew's House, the official residence of theFirst MinisteratBute Houseand Scottish Government offices atVictoria Quay. Other major sectors across the city include administrative and support services, the education sector, public administration and defence, the health and social care sector, scientific and technical services, and construction and manufacturing.[185]When the £1.3bn Edinburgh & South East Scotland City Region Deal[186]was signed in 2018, the region's Gross Value Added (GVA) contribution to theScottish economywas cited as £33bn, or 33% of the country's output. The City Region Deal funds a range of "Data Driven Innovation" hubs which are using data to innovate in the region, recognising the region's strengths in technology and data science, the growing importance of the data economy, and the need to tackle the digital skills gap, as a route to social and economic prosperity.[187][188][189]

Tourism is also an important element in the city's economy. As a World Heritage Site, tourists visit historical sites such as Edinburgh Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse and the Old and New Towns. Their numbers are augmented in August each year during theEdinburgh Festivals, which attracts 4.4 million visitors,[190]and generates over £100M for the local economy.[191]In March 2010, unemployment in Edinburgh was comparatively low at 3.6%, and it remains consistently below the Scottish average of 4.5%.[190]In 2022 Edinburgh was the second most visited city in the United Kingdom, behindLondon, by overseas visitors.[192]

Culture

[edit]Festivals and celebrations

[edit]Edinburgh festivals

[edit]

The city hosts a series of festivals that run between the end of July and early September each year. The best known of these events are theEdinburgh Festival Fringe, the Edinburgh International Festival, theEdinburgh Military Tattoo, theEdinburgh Art Festivaland theEdinburgh International Book Festival.[193]

The longest established of these festivals is the Edinburgh International Festival, which was first held in 1947[194]and consists mainly of a programme of high-profile theatre productions and classical music performances, featuring international directors, conductors, theatre companies and orchestras.[195]

This has since been overtaken in size by the Edinburgh Fringe which began as a programme of marginal acts alongside the "official" Festival and has become the world's largest performing arts festival. In 2017, nearly 3400 different shows were staged in 300 venues across the city.[196][197]Comedy has become one of the mainstays of the Fringe, with numerous well-known comedians getting their first 'break' there, often by being chosen to receive theEdinburgh Comedy Award.[198]The Edinburgh Military Tattoo, occupies the Castle Esplanade every night for three weeks each August, with massedpipe bandsandmilitary bandsdrawn from around the world. Performances end with a short fireworks display.

As well as the summer festivals,many other festivals are held during the rest of the year, including theEdinburgh International Film Festival[199]andEdinburgh International Science Festival.[200]

The summer of 2020 was the first time in its 70-year history that the Edinburgh festival was not run, being cancelled due to theCOVID-19 pandemic.[201]This affected many of the tourist-focused businesses in Edinburgh which depend on the various festivals over summer to return an annual profit.[202]

Edinburgh's Hogmanay

[edit]

The annual EdinburghHogmanaycelebration was originally an informal street party focused on theTron Kirkin the Old Town's High Street. Since 1993, it has been officially organised with the focus moved to Princes Street. In 1996, over 300,000 people attended, leading to ticketing of the main street party in later years up to a limit of 100,000 tickets.[203]Hogmanay now covers four days of processions, concerts and fireworks, with the street party beginning on Hogmanay. Alternative tickets are available for entrance into the Princes Street Gardens concert andCèilidh, where well-known artists perform and ticket holders can participate in traditional Scottish cèilidh dancing. The event attracts thousands of people from all over the world.[203]

Beltane and other festivals

[edit]On the night of 30 April theBeltane Fire Festivaltakes place on Calton Hill, involving a procession followed by scenes inspired bypaganold spring fertility celebrations.[204]At the beginning of October each year theDussehraHindu Festival is also held on Calton Hill.[205]

Music, theatre and film

[edit]

Outside the Festival season, Edinburgh supports several theatres and production companies. TheRoyal Lyceum Theatrehas its own company, while theKing's Theatre,Edinburgh Festival TheatreandEdinburgh Playhousestage large touring shows. TheTraverse Theatrepresents a more contemporary repertoire.Amateur theatre companiesproductions are staged at theBedlam Theatre,Church Hill TheatreandKing's Theatreamong others.[206]

TheUsher Hallis Edinburgh's premier venue for classical music, as well as occasional popular music concerts.[207]It was the venue for theEurovision Song Contest 1972. Other halls staging music and theatre includeThe Hub, theAssembly Roomsand theQueen's Hall. TheScottish Chamber Orchestrais based in Edinburgh.[208]

Edinburgh has one repertory cinema,The Cameo, and formerly, theEdinburgh Filmhouseas well as the independentDominion Cinemaand a range ofmultiplexes.[209]

Edinburgh has a healthy popular music scene. Occasionally large concerts are staged atMurrayfieldandMeadowbank, while mid-sized events take place at smaller venues such as 'The Corn Exchange', 'The Liquid Rooms' and 'The Bongo Club'. In 2010,PRS for Musiclisted Edinburgh among the UK's top ten 'most musical' cities.[210]Several city pubs are well known for their live performances offolk music. They include 'Sandy Bell's' in Forrest Road, 'Captain's Bar' in South College Street and 'Whistlebinkies' in South Bridge.

Like many other cities in the UK, numerous nightclub venues hostElectronic dance musicevents.[211]

Edinburgh is home to a flourishing group of contemporary composers such asNigel Osborne, Peter Nelson, Lyell Cresswell,Hafliði Hallgrímsson, Edward Harper, Robert Crawford, Robert Dow andJohn McLeod. McLeod's music is heard regularly on BBC Radio 3 and throughout the UK.[212]

Media

[edit]Newspapers

[edit]The main local newspaper is theEdinburgh Evening News. It is owned and published alongside its sister titlesThe ScotsmanandScotland on SundaybyJPIMedia.[213]Student newspapers include,The JournalScotland wide Universities, andThe StudentUniversity of Edinburghwhich was founded in 1887. Community newspapers includeThe Spurtlefrom Broughton,Spokes Bulletin, andThe Edinburgh Reporter.

Radio

[edit]The city has many commercial radio stations includingForth 1, a station which broadcasts mainstream chart music, Greatest Hits Edinburgh on DAB which plays classic hits and Edge Radio.[214]Capital ScotlandandHeart Scotlandalso have transmitters covering Edinburgh. Along with the UK national radio stations,BBC Radio Scotlandand the Gaelic language serviceBBC Radio nan Gàidhealare also broadcast. DAB digital radio is broadcast over two local multiplexes.BFBSRadio broadcasts from studios on the base at Dreghorn Barracks across the city on 98.5FM as part of its UK Bases network. Small scale DAB started October 2022 with numerous community stations on board.

Television

[edit]Television, along with most radio services, is broadcast to the city from theCraigkelly transmitting stationsituated in Fife on the opposite side of the Firth of Forth[215]and theBlack Hill transmitting stationinNorth Lanarkshireto the west.

There are no television stations based in the city. Edinburgh Television existed in the late 1990s to early 2003[216]andSTV Edinburghexisted from 2015 to 2018.[217][218]

Museums, libraries and galleries

[edit]

Edinburgh has many museums and libraries. These include theNational Museum of Scotland, theNational Library of Scotland,National War Museum, theMuseum of Edinburgh,Surgeons' Hall Museum, theWriters' Museum, theMuseum of ChildhoodandDynamic Earth. TheMuseum on The Moundhas exhibits on money and banking.[219]

Edinburgh Zoo, covering 82 acres (33 ha) on Corstorphine Hill, is the second most visited paid tourist attraction in Scotland,[220]and was previously home to twogiant pandas, Tian Tian and Yang Guang, on loan from the People's Republic of China. Edinburgh is also home toThe Royal Yacht Britannia, decommissioned in 1997 and now a five-star visitor attraction and evening events venue permanently berthed atOcean Terminal.

Edinburgh contains Scotland's threeNational Galleriesof Art as well as numerous smaller art galleries.[221]The national collection is housed in theScottish National Gallery, located on The Mound, comprising the linked National Gallery of Scotland building and theRoyal Scottish Academy building. Contemporary collections are shown in theScottish National Gallery of Modern Artwhich occupies a split site at Belford. TheScottish National Portrait Galleryon Queen Street focuses on portraits and photography.

The council-ownedCity Art Centrein Market Street mounts regular art exhibitions. Across the road,The Fruitmarket Galleryoffers world-class exhibitions of contemporary art, featuring work by British and international artists with both emerging and established international reputations.[222]

The city hosts several of Scotland's galleries and organisations dedicated to contemporary visual art. Significant strands of this infrastructure includeCreative Scotland,Edinburgh College of Art,Talbot Rice Gallery(University of Edinburgh),Collective Gallery(based at theCity Observatory) and theEdinburgh Annuale.

There are also many small private shops/galleries that provide space to showcase works from local artists.[223]

Shopping

[edit]The locale aroundPrinces Streetis the main shopping area in the city centre, with souvenir shops, chain stores such asBoots the Chemist,Edinburgh Woollen Mill, andH&M.[224]George Street, north of Princes Street, has several upmarket shops and independent stores.[224]At the east end of Princes Street, the redevelopedSt James Quarteropened its doors in June 2021,[225]while next to theBalmoral Hoteland Waverley Station isWaverley Market.Multrees Walkis a pedestrian shopping district, dominated by the presence ofHarvey Nichols, and other names includingLouis Vuitton,MulberryandMichael Kors.[224]

Edinburgh also has substantial retail parks outside the city centre. These includeThe Gyle Shopping Centreand Hermiston Gait in the west of the city,Cameron Toll Shopping Centre, Straiton Retail Park (actually just outside the city, in Midlothian) andFort Kinnairdin the south and east, andOcean Terminalin the north on theLeithwaterfront.[226]

Government and politics

[edit]Government

[edit]

Following local government reorganisation in 1996, the City of Edinburgh Council constitutes one of the32 council areas of Scotland.[227]Like all otherlocal authorities of Scotland, the council has powers over most matters of local administration such as housing, planning,local transport, parks, economic development and regeneration.[228]The council comprises 63 electedcouncillors, returned from 17multi-member electoral wardsin the city.[229]Following the2007 City of Edinburgh Council electionthe incumbentLabour Partylost majority control of the council after 23 years to aLiberal Democrat/SNPcoalition.[230]

After the 2017 election, the SNP and Labour formed a coalition administration, which lasted until the next election in 2022. The2022 City of Edinburgh Council electionresulted in the most politically balanced council in the UK, with 19 SNP, 13 Labour, 12 Liberal Democrat, 10 Green and 9 Conservative councillors. A minority Labour administration was formed, being voted in by Scottish Conservative and Scottish Liberal Democrat councillors. The SNP and Greens presented a coalition agreement, but could not command majority support in the council. This caused controversy amongst the Scottish Labour Party group for forming an administration supported by Conservatives and led to the suspension of two Labour councillors on the council for abstaining on the vote to approve the new administration.[231]The city'scoat of armswas registered by theLord Lyon King of Armsin 1732.[232]

Politics

[edit]Edinburgh, like all of Scotland, is represented in theScottish Parliament, situated in theHolyroodarea of the city. For electoral purposes, the city is divided into six constituencies which, along with 3 seats outside of the city, form part of theLothian region.[233]Each constituency elects oneMember of the Scottish Parliament(MSP) by thefirst past the postsystem of election, and the region elects sevenadditional MSPsto produce a result based on a form of proportional representation.[233]

As of the2021 election, the Scottish National Party have four MSPs:Ash DenhamforEdinburgh Eastern,Ben MacphersonforEdinburgh Northern and LeithandGordon MacDonaldforEdinburgh PentlandsandAngus RobertsonforEdinburgh Centralconstituencies.Alex Cole-Hamilton, the Leader of theScottish Liberal DemocratsrepresentsEdinburgh WesternandDaniel Johnsonof theScottish Labour PartyrepresentsEdinburgh Southernconstituency. In addition, the city is also represented by seven regional MSPs representing the Lothian electoral region: The Conservatives have three regional MSPs:Jeremy Balfour,Miles BriggsandSue Webber, Labour have two regional MSPs:Sarah BoyackandFoysol Choudhury; two Scottish Green regional MSPs were elected: Green's Co-LeaderLorna SlaterandAlison Johnstone. However, following her election as thePresiding Officerof the 6th Session of the Scottish Parliament on 13 May 2021, Alison Johnstone has abided by the established parliamentary convention for speakers and renounced all affiliation with her former political party for the duration of her term as Presiding Officer. So she presently sits as an independent MSP for the Lothians Region.[citation needed]

Edinburgh is also represented in theHouse of Commons of the United Kingdomby fiveMembers of Parliament. The city is divided intoEdinburgh North and Leith,Edinburgh East,Edinburgh South,Edinburgh South West, andEdinburgh West,[234]each constituency electing one member by the first past the post system. Since the2019 UK General election, Edinburgh is represented by threeScottish National PartyMPs (Deirdre Brock, Edinburgh North and Leith/Tommy Sheppard, Edinburgh East/Joanna Cherry, Edinburgh South West), oneLiberal DemocratMP in Edinburgh West (Christine Jardine) and oneLabourMP in Edinburgh South (Ian Murray).

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]

Edinburgh Airportis Scotland's busiest airport and the principal international gateway to the capital, handling over 14.7 million passengers; it was also thesixth-busiest airport in the United Kingdomby total passengers in 2019.[235][236]In anticipation of rising passenger numbers, the former operator of the airportBAAoutlined a draft masterplan in 2011 to provide for the expansion of the airfield and the terminal building. In June 2012,Global Infrastructure Partnerspurchased the airport for £807 million.[237]The possibility of building a second runway to cope with an increased number of aircraft movements has also been mooted.[238]

Buses

[edit]

Travel in Edinburgh is undertaken predominantly by bus.Lothian Buses, the successor company to Edinburgh Corporation Transport Department, operate the majority ofcity bus serviceswithin the city and to surrounding suburbs, with the most routes running via Princes Street. Services further afield operate from theEdinburgh Bus StationoffSt Andrew Squareand Waterloo Place and are operated mainly byStagecoach East Scotland,Scottish Citylink,National Express CoachesandBorders Buses.

Lothian Buses andMcGill's Scotland Eastoperate the city's branded publictour buses. Thenight busservice and airport buses are mainly operated by Lothian Buses link.[239]In 2019, Lothian Buses recorded 124.2 million passenger journeys.[240]

To tackletraffic congestion, Edinburgh is now served by sixpark & ridesites on the periphery of the city at Sheriffhall (in Midlothian),Ingliston,Riccarton,Inverkeithing(in Fife),NewcraighallandStraiton(in Midlothian). Areferendumof Edinburgh residents in February 2005 rejected a proposal to introducecongestion chargingin the city.[241]

Railway

[edit]

Edinburgh Waverleyis the second-busiest railway station in Scotland, with onlyGlasgow Centralhandling more passengers. On the evidence of passenger entries and exits between April 2015 and March 2016, Edinburgh Waverley is the fifth-busiest station outside London; it is also the UK's second biggest station in terms of the number of platforms and area size.[242]Waverley is the terminus for most trains arriving fromLondon King's Crossand the departure point for manyrail services within Scotlandoperated byScotRail.

To the west of the city centre liesHaymarket station, which is an important commuter stop. Opened in 2003,Edinburgh Parkstation serves the Gyle business park in the west of the city and the nearbyGogarburnheadquarters of the Royal Bank of Scotland. TheEdinburgh Crossrailroute connects Edinburgh Park with Haymarket, Edinburgh Waverley and the suburban stations ofBrunstaneandNewcraighallin the east of the city.[243]There are also commuter lines toEdinburgh Gateway,South Gyleand Dalmeny, the latter servingSouth Queensferryby the Forth Bridges, and toWester HailesandCurriehillin the south-west of the city.

Trams

[edit]

Edinburgh Tramsbecame operational on 31 May 2014. The city had been without a tram system sinceEdinburgh Corporation Tramwaysceased on 16 November 1956.[244]Following parliamentary approval in 2007, construction began in early 2008. The first stage of the project was expected to be completed by July 2011[245]but, following delays caused by extra utility work and a long-running contractual dispute between the council and the main contractor,Bilfinger SE, the project was rescheduled.[246][247][248]The line opened in 2014 but had been cut short to 8.7 mi (14.0 km) in length, running fromEdinburgh AirportToYork Placein the east end of the city.

The line was later extended north ontoLeithandNewhavenopening a further eight stops to passengers in June 2023. The York Place stop was replaced by a new island stop atPicardy Place. The original plan would have seen a second line run from Haymarket throughRavelstonandCraigleithtoGranton Squareon theWaterfront Edinburgh.This was shelved in 2011 but is now once again under consideration, as is another line potentially linking the south of the city and theBioquarter.[249]There were also long-term plans for lines running west from the airport toRathoandNewbridgeand another connectingGrantonto Newhaven via Lower Granton Road. Lothian Buses and Edinburgh Trams are both owned and operated byTransport for Edinburgh.

Despite its modern transport links, in January 2021 Edinburgh was named the most congested city in the UK for the fourth year running, though has since fallen to 7th place in 2022[250][251]

Education

[edit]Schools

[edit]There are 18 nursery, 94 primary and 23 secondaryschoolsadministered by the City of Edinburgh Council.[252]Edinburgh is home toThe Royal High School, one of theoldest schools in the countryandthe world. The city also has severalindependent, fee-paying schoolsincludingEdinburgh Academy,Fettes College,George Heriot's School,George Watson's College,Merchiston Castle School,Stewart's Melville CollegeandThe Mary Erskine School. In 2009, the proportion of pupils attending independent schools was 24.2%, far above the Scottish national average of just over 7% and higher than in any other region of Scotland.[253]In August 2013, the City of Edinburgh Council opened the city's first stand-alone Gaelic primary school,Bun-sgoil Taobh na Pàirce.[254]

College and university

[edit]

There are three universities in Edinburgh: theUniversity of Edinburgh,Heriot-Watt UniversityandEdinburgh Napier University.

Established by royal charter in 1583, the University of Edinburgh is one of Scotland'sancient universitiesand is the fourth oldest in the country afterSt Andrews,GlasgowandAberdeen.[255]Originally centred onOld Collegethe university expanded to premises on The Mound, the Royal Mile and George Square.[255]Today, theKing's Buildingsin the south of the city contain most of the schools within the College of Science and Engineering. In 2002, themedical schoolmoved to purpose built accommodation adjacent to the newRoyal Infirmary of EdinburghatLittle France. The university is placed 16th in the QS World University Rankings for 2022.[256]

Heriot-Watt University is based at theRiccartoncampus in the west of Edinburgh. Originally established in 1821, as the world's firstmechanics' institute, it was granted university status by royal charter in 1966. It has other campuses in the Scottish Borders, Orkney, United Arab Emirates and Putrajaya in Malaysia. It takes the nameHeriot-Wattfrom Scottish inventorJames Wattand Scottish philanthropist and goldsmithGeorge Heriot. Heriot-Watt University has been named International University of the Year byThe Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide 2018. In the latest Research Excellence Framework, it was ranked overall in the Top 25% of UK universities and 1st in Scotland for research impact.

Edinburgh Napier University was originally founded as the Napier College, which was renamed Napier Polytechnic in 1986 and gained university status in 1992.[257]Edinburgh Napier University has campuses in the south and west of the city, including the formerMerchiston TowerandCraiglockhart Hydropathic.[257]It is home to theScreen Academy Scotland.

Queen Margaret Universitywas located in Edinburgh before it moved to a new campus just outside the city boundary on the edge ofMusselburghin 2008.[258]Until 2012, further education colleges in the city includedJewel and Esk College(incorporatingLeith Nautical Collegefounded in 1903),Telford College, opened in 1968, andStevenson College, opened in 1970. These have now been amalgamated to formEdinburgh College.Scotland's Rural Collegealso has a campus in south Edinburgh. Other institutions include theRoyal College of Surgeons of Edinburghand theRoyal College of Physicians of Edinburghwhich were established by royal charter in 1506 and 1681 respectively. The Trustees Drawing Academy of Edinburgh, founded in 1760, became theEdinburgh College of Artin 1907.[259]

Healthcare

[edit]

The mainNHS Lothianhospitals serving the Edinburgh area are theRoyal Infirmary of Edinburgh, which includes theUniversity of Edinburgh Medical School, and theWestern General Hospital,[260]which has a large cancer treatment centre and nurse-led Minor Injuries Clinic.[261]TheRoyal Edinburgh Hospitalin Morningside specialises in mental health. TheRoyal Hospital for Children and Young People, colloquially referred to asthe Sick Kids, is a specialistpaediatricshospital.

There are two private hospitals: Murrayfield Hospital in the west of the city and Shawfair Hospital in the south; both are owned bySpire Healthcare.[260]

Sport

[edit]Football

[edit]Men's

[edit]Edinburgh has fourfootballclubs that play in theScottish Professional Football League(SPFL):Heart of Midlothian, founded in 1874,Hibernian, founded in 1875,Edinburgh City F.C., founded in 1966 andSpartans, founded in 1951.

Heart of Midlothian and Hibernian are known locally as "Hearts" and "Hibs", respectively. Both play in theScottish Premiership.[262]They are the oldest city rivals in Scotland and theEdinburgh derbyis one of the oldest derby matches in world football. Both clubs have won theScottish league championshipfour times. Hearts have won theScottish Cupeight times and theScottish League Cupfour times. Hibs have won the Scottish Cup and the Scottish League Cup three times each.Edinburgh Citywere promoted toScottish League Twoin the 2015–16 season, becoming the first club to win promotion to the SPFL via the pyramid system playoffs.

Edinburgh was also home to four otherformer Scottish Football League clubs: the originalEdinburgh City(founded in 1928),Leith Athletic,Meadowbank ThistleandSt Bernard's. Meadowbank Thistle played atMeadowbank Stadiumuntil 1995, when the club moved toLivingstonand becameLivingston F.C. TheScottish national teamhas very occasionally played atEaster RoadandTynecastle, although its normalhome stadiumisHampden Parkin Glasgow. St Bernard's'New Logie Greenwas used to host the1896 Scottish Cup Final, the only time the match has been played outside Glasgow.[263]

The city also plays host toLowland Football LeagueclubsCivil Service Strollers,Edinburgh UniversityandSpartans, as well asEast of Scotland LeagueclubsCraigroyston,Edinburgh United,Heriot-Watt University,Leith Athletic,Lothian Thistle Hutchison Vale, andTynecastle.

Women's

[edit]In women's football,Hearts,HibsandSpartansplay in theSWPL 1.[264]Hutchison ValeandBoroughmuir Thistleplay in theSWPL 2.[265]

Rugby

[edit]TheScotland national rugby union teamplay atMurrayfield Stadium, and the professionalEdinburgh Rugbyteam play at the nextdoorEdinburgh Rugby Stadium; both are owned by theScottish Rugby Unionand are also used for other events, including music concerts. Murrayfield is the largest capacity stadium in Scotland, seating 67,144 spectators.[266]Edinburgh is also home toScottish PremiershipteamsBoroughmuir RFC,Currie RFC, theEdinburgh Academicals,Heriot's Rugby ClubandWatsonians RFC.[267]

The Edinburgh Academicals ground atRaeburn Placewas the location of the world's first international rugby game on 27 March 1871, between Scotland and England.[268]

Rugby leagueis represented by theEdinburgh Eagleswho play in theRugby League Conference Scotland Division. Murrayfield Stadium has hosted theMagic Weekendwhere allSuper Leaguematches are played in the stadium over one weekend.

-

Edinburgh Marathon

-

Murrayfield Ice Rink

Other sports

[edit]TheScottish cricket team, which represents Scotland internationally, play their home matches at theGrange cricket club.[269]

TheEdinburgh Capitalsare the latest of a succession ofice hockeyclubs in the Scottish capital. Previously Edinburgh was represented by theMurrayfield Racers (2018), the originalMurrayfield Racers(who folded in 1996)and the Edinburgh Racers. The club play their home games at theMurrayfield Ice Rinkand have competed in the eleven-team professionalScottish National League (SNL)since the 2018–19 season.[270]

Next door to Murrayfield Ice Rink is a 7-sheeter dedicatedcurlingfacility where curling is played from October to March each season.

Caledonia Prideare the only women's professional basketball team in Scotland. Established in 2016, the team compete in the UK wideWomen's British Basketball Leagueand play their home matches at theOriamNational Performance Centre. Edinburgh also has several men's basketball teams within the Scottish National League.Boroughmuir Blaze,City of Edinburgh KingsandEdinburgh Lionsall compete in Division 1 of the National League, andPleasance B.C.compete in Division 2.

TheEdinburgh Diamond Devilsis a baseball club which won its first Scottish Championship in 1991 as the "Reivers". 1992 saw the team repeat the achievement, becoming the first team to do so in league history. The same year saw the start of their first youth team, the Blue Jays. The club adopted its present name in 1999.[271]

Edinburgh has also hosted national and international sports events including theWorld Student Games, the1970 British Commonwealth Games,[272]the1986 Commonwealth Games[272]and the inaugural 2000 Commonwealth Youth Games.[273]For the 1970 Games the city built Olympic standard venues and facilities including Meadowbank Stadium and theRoyal Commonwealth Pool. The Pool underwent refurbishment in 2012 and hosted the Diving competition in the2014 Commonwealth Gameswhich were held in Glasgow.[274]

InAmerican football, theScottish ClaymoresplayedWLAF/NFL Europegames at Murrayfield, including theirWorld Bowl 96victory. From 1995 to 1997 they played all their games there, from 1998 to 2000 they split their home matches between Murrayfield and Glasgow's Hampden Park, then moved to Glasgow full-time, with one final Murrayfield appearance in 2002.[275]The city's most successful non-professional team are theEdinburgh Wolveswho play at Meadowbank Stadium.[276]

TheEdinburgh Marathonhas been held annually in the city since 2003 with more than 16,000 runners taking part on each occasion.[277]Its organisers have called it "the fastest marathon in the UK" due to the elevation drop of 40 m (130 ft).[278]The city also organises a half-marathon, as well as10 km(6.2 mi) and5 km(3.1 mi) races, including a 5 km (3 mi) race on 1 January each year.

Edinburgh has aspeedwayteam, theEdinburgh Monarchs, which, since the loss of its stadium in the city, has raced at the Lothian Arena inArmadale, West Lothian. The Monarchs have won thePremier Leaguechampionship five times in their history, in 2003[279]and again in 2008,[280]2010, 2014 and 2015.

For basketball, the city has a basketball club,Edinburgh Tigers.[citation needed]

People

[edit]