Auckland

Auckland(/ˈɔːklənd/AWK-lənd;[6]Māori:Tāmaki Makaurau) is a large metropolitan city in theNorth Islandof New Zealand. It has an urban population of about 1,478,800 (June 2023).[4]It is located in the greaterAuckland Region, the area governed byAuckland Council, which includes outlying rural areas and the islands of theHauraki Gulf, and which has a total population of 1,739,300 as of June 2023.[4]It is themost populous cityof New Zealand and thefifth largest cityin Oceania. WhileEuropeanscontinue to make up the plurality of Auckland's population, the city became multicultural andcosmopolitanin the late-20th century, withAsiansaccounting for 31% of the city's population in 2018.[7]Auckland has the fourth largestforeign-bornpopulation in the world, with 39% of its residents born overseas.[8]With its large population ofPasifika New Zealanders, the city is also home to the biggest ethnicPolynesianpopulation in the world.[9]TheMāori-languagename for Auckland isTāmaki Makaurau, meaning "Tāmaki desired by many", in reference to the desirability of its natural resources and geography.Tāmakimeans "omen".[10][11]

Auckland lies between theHauraki Gulfto the east, theHunua Rangesto the south-east, theManukau Harbourto the south-west, and theWaitākere Rangesand smaller ranges to the west and north-west. The surrounding hills are covered inrainforestand the landscape is dotted with 53 volcanic centres that make up theAuckland Volcanic Field. The central part of the urban area occupies a narrowisthmusbetween the Manukau Harbour on theTasman Seaand theWaitematā Harbouron the Pacific Ocean. Auckland is one of the few cities in the world to have a harbour on each of two separate major bodies of water.

TheAuckland isthmuswas first settledc. 1350and was valued for its rich and fertile land. TheMāoripopulation in the area is estimated to have peaked at 20,000 before the arrival of Europeans.[12]After aBritish colonywas established in New Zealand in 1840,William Hobson, then Lieutenant-Governor of New Zealand, chose Auckland as its newcapital.Ngāti Whātua Ōrākeimade a strategic gift of land to Hobson for the new capital. Hobson named the area afterGeorge Eden, Earl of Auckland, BritishFirst Lord of the Admiralty. Māori–European conflict over land in the region led to war in the mid-19th century. In 1865, Auckland was replaced byWellingtonas the capital, but continued to grow, initially because of its port and the logging and gold-mining activities in its hinterland, and later because of pastoral farming (especially dairy farming) in the surrounding area, and manufacturing in the city itself.[13]It has been the nation's largest city throughout most of its history. Today,Auckland's central business districtis New Zealand's leading economic hub.

TheUniversity of Auckland, founded in 1883, is the largest university in New Zealand. The city's significant tourist attractions include national historic sites, festivals, performing arts, sports activities and a variety of cultural institutions, such as theAuckland War Memorial Museum, theMuseum of Transport and Technology, and theAuckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Its architectural landmarks include theHarbour Bridge, theTown Hall, theFerry Buildingand theSky Tower, which is the second-tallest building in theSouthern HemisphereafterThamrin Nine.[14]The city is served byAuckland Airport, which handles around 2 million international passengers a month. Despite being one of the mostexpensivecities in the world,[15]Auckland is one of the world'smost liveable cities, ranking third in the 2019 Mercer Quality of Living Survey and at first place in a 2021 ranking of theGlobal Liveability RankingbyThe Economist.[16][17][18]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

TheAuckland isthmuswas settled byMāoriaround 1350, and was valued for its rich and fertile land. Manypā(fortified villages) were created, mainly on the volcanic peaks. By the early 1700s,Te Waiohua, a confederation of tribes such asNgā Oho, Ngā Riki and Ngā Iwi, became the main influential force on the Auckland isthmus,[20][21]with majorpālocated atMaungakiekie / One Tree Hill,Māngere MountainandMaungataketake.[22]The confederation came to an end around 1741, whenparamount chiefKiwi Tāmakiwas killed in battle byNgāti WhātuahapūTe Taoūchief Te Waha-akiaki.[23]From the 1740s onwards,Ngāti Whātua Ōrākeibecame the major influential force on the Auckland isthmus.[20]The Māori population in the area is estimated to have been about 20,000 before the arrival of Europeans.[24][25]The introduction of firearms at the end of the eighteenth century, which began inNorthland, upset the balance of power and led to devastatingintertribal warfarebeginning in 1807, causingiwiwho lacked the new weapons to seek refuge in areas less exposed to coastal raids. As a result, the region had relatively low numbers of Māori when settlement byEuropean New Zealandersbegan.[26][27]

On 20 March 1840 in theManukau Harbourarea where Ngāti Whātua farmed, paramount chiefApihai Te Kawausigned theTreaty of Waitangi.[28]Ngāti Whātua sought British protection fromNgāpuhias well as a reciprocal relationship with theCrownand theChurch. Soon after signing the treaty, Ngāti Whātua Ōrākei made a strategic gift of 3,500 acres (1,400 ha) of land on theWaitematā Harbourto the new Governor of New Zealand,William Hobson, for the newcapital, which Hobson named forGeorge Eden, Earl of Auckland, thenViceroy of India.[29][30][31]Auckland was founded on 18 September 1840 and was officially declared New Zealand's capital in 1841,[32][33]and the transfer of the administration from Russell (nowOld Russell) in the Bay of Islands was completed in 1842. However, even in 1840Port Nicholson(later renamedWellington) was seen as a better choice for an administrative capital because of its proximity to theSouth Island, and Wellington became the capital in 1865. After losing its status as capital, Auckland remained the principal city of theAuckland Provinceuntil the provincial system was abolished in 1876.[34]

In response to the ongoing rebellion byHōne Hekein the mid-1840s, the government encouraged retired but fit British soldiers and their families to migrate to Auckland to form a defence line around the port settlement as garrison soldiers. By the time the firstFenciblesarrived in 1848, theNorthern Warhad concluded. Outlying defensive towns were then constructed to the south, stretching in a line from the port village ofOnehungain the west toHowickin the east. Each of the four settlements had about 800 settlers; the men were fully armed in case of emergency, but spent nearly all their time breaking in the land and establishing roads.[citation needed]

In the early 1860s, Auckland became a base against theMāori King Movement,[36]and the 12,000 Imperial soldiers stationed there led to a strong boost to local commerce.[37]This, andcontinued road building towards the southinto theWaikatoregion, enabledPākehā(European New Zealanders) influence to spread from Auckland. The city's population grew fairly rapidly, from 1,500 in 1841 to 3,635 in 1845,[37]then to 12,423 by 1864. The growth occurred similarly to othermercantile-dominated cities, mainly around the port and with problems of overcrowding and pollution. Auckland's population of ex-soldiers was far greater than that of other settlements: about 50 per cent of the population was Irish, which contrasted heavily with the majority English settlers in Wellington,ChristchurchorNew Plymouth. The majority of settlers in the early period were assisted by receiving cheap passage to New Zealand.[38]

Modern history

[edit]

Trams and railway lines shaped Auckland's rapid expansion in the early first half of the 20th century. However, after the Second World War, the city's transport system and urban form became increasingly dominated by the motor vehicle.[citation needed]Arterial roads and motorways became both defining and geographically dividing features of the urban landscape. They also allowed further massive expansion that resulted in the growth of suburban areas such as theNorth Shore(especially after the construction of theAuckland Harbour Bridgein the late 1950s), andManukau Cityin the south.[39]

Economic deregulation in the mid-1980s led to very dramatic changes to Auckland's economy, and many companies relocated their head offices from Wellington to Auckland. The region was now the nerve centre of the entire national economy. Auckland also benefited from a surge in tourism, which brought 75 per cent of New Zealand's international visitors through its airport. Auckland's port handled 31 per cent of the country's container trade in 2015.[40]

The face of urban Auckland changed when the government's immigration policy began allowing immigrants from Asia in 1986. This has led to Auckland becoming a multicultural city, with people of all ethnic backgrounds. According to the 1961 census data, Māori and Pacific Islanders comprised 5 per cent of Auckland's population; Asians less than 1 per cent.[41]By 2006, the Asian population had reached 18.0 per cent in Auckland, and 36.2 per cent in the central city. New arrivals from Hong Kong,TaiwanandKoreagave a distinctive character to the areas where they clustered, while a range of other immigrants introduced mosques,Hindutemples,halalbutchers and ethnic restaurants to the suburbs.[40]

Geography

[edit]

Scope

[edit]The boundaries of Auckland are imprecisely defined. The Aucklandurban area, as it is defined byStatistics New Zealandunder theStatistical Standard for Geographic Areas 2018(SSGA18), spans 607.07 square kilometres (234.39 sq mi) and extends toLong Bayin the north,Swansonin the north-west, and Runciman in the south.[3]Auckland'sfunctional urban area(commuting zone) extends from just south ofWarkworthin the north toMeremerein the south, incorporating theHibiscus Coastin the northeast,Helensville,Parakai,Muriwai,Waimauku,Kumeū-Huapai, andRiverheadin the northwest,Beachlands-Pine HarbourandMaraetaiin the east, andPukekohe,Clarks Beach,Patumāhoe,Waiuku,TuakauandPōkeno(the latter two in the Waikato region) in the south.[42]Auckland formsNew Zealand's largest urban area.[4]

The Auckland urban area lies within theAuckland Region, an administrative region that takes its name from the city. The region encompasses the city centre, as well as suburbs, surrounding towns, nearshore islands, and rural areas north and south of the urban area.[43]

TheAuckland central business districtis the most built-up area of the region. The CBD covers 433 hectares (1,070 acres) in a triangular area,[44]and is bounded by theAuckland waterfronton the Waitematā Harbour[45]and the inner-city suburbs ofPonsonby,NewtonandParnell.[44]

Harbours and gulf

[edit]

The central areas of the city are located on theAuckland isthmus, less than two kilometres wide at its narrowest point, betweenMāngere Inletand theTamaki River. There are two harbours surrounding this isthmus:Waitematā Harbourto the north, which extends east to theHauraki Gulfand thence to the Pacific Ocean, andManukau Harbourto the south, which opens west to theTasman Sea.

Bridges span parts of both harbours, notably theAuckland Harbour Bridgecrossing the Waitematā Harbour west of the central business district. TheMāngere Bridgeand theUpper Harbour Bridgespan the upper reaches of the Manukau and Waitematā Harbours, respectively. In earlier times,portagescrossed the narrowest sections of the isthmus.[46][47]

Several islands of the Hauraki Gulf are administered as part of the Auckland Region, though they are not part of the Auckland urban area. Parts ofWaiheke Islandeffectively function as Auckland suburbs, while various smaller islands near Auckland are mostly zoned 'recreational open space' or are nature sanctuaries.[citation needed]

Climate

[edit]Under theKöppen climate classification, Auckland has anoceanic climate(Köppen climate classificationCfb). However, under theTrewartha climate classificationand according to theNational Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research(NIWA), the city's climate is classified ashumid subtropical climatewith warm summers and mild winters (Trewartha climate classificationCfbl).[48][49]It is the warmest main centre of New Zealand. The average daily maximum temperature is 23.7 °C (74.7 °F) in February and 14.7 °C (58.5 °F) in July. The maximum recorded temperature is 34.4 °C (93.9 °F) on 12 February 2009,[50]while the minimum is −3.9 °C (25.0 °F), although there is also an unofficial low of −5.7 °C (21.7 °F) recorded atRiverhead Forestin June 1936.[51]

Snowfallis extremely rare: the most significant fall since the start of the 20th century was on 27 July 1939, when snow fell just before dawn and five centimetres (2 in) of snow reportedly lay onMount Eden.[52][53]Snowflakes were also seen on 28 July 1930 and 15 August 2011.[54][55][56]

Frostsin Auckland are infrequent and often localised. Henderson Riverpark receives an annual average of 27.4ground frostsper year, while Auckland Airport receives an annual average of 8.7 ground frosts per year.[57]

Averagesea temperaturearound Auckland varies throughout the year. The water temperature is warmest in February when it averages 21 °C (70 °F), while in August, the water temperature is at its coolest, averaging 14 °C (57 °F).[58]

Prevailing windsin Auckland are predominantly from the southwest. The mean annual wind speed for Auckland Airport is 18 kilometres per hour (11 mph).[59]During the summer months there is often asea breezein Auckland which starts in the morning and dies down again in the evening.[60]The early morning calm on the isthmus during settled weather, before the sea breeze rises, was described as early as 1853: "In all seasons, the beauty of the day is in the early morning. At that time, generally, a solemn stillness holds, and a perfect calm prevails...".[61]

Fogis a common occurrence for Auckland, especially in autumn and winter. Whenuapai Airport experiences an average of 44 fog days per year.[62]

Auckland occasionally suffers from air pollution due tofine particleemissions.[63]There are also occasional breaches of guideline levels ofcarbon monoxide.[64]While maritime winds normally disperse the pollution relatively quickly it can sometimes become visible as smog, especially on calm winter days.[65]

| Climate data forAuckland Airport(17km S of Auckland, 7m ASL, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1962–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

21.0 (69.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.6 (74.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.5 (86.9) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 27.4 (81.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26 (79) |

24 (75) |

21.2 (70.2) |

18.9 (66.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 23.9 (75.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

22.9 (73.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

15.5 (59.9) |

14.6 (58.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.0 (68.0) |

20.5 (68.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

16.6 (61.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) |

16.6 (61.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

10.8 (51.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

8.3 (46.9) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.0 (59.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

12.4 (54.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.6 (36.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.6 (40.3) |

6.7 (44.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.5 (50.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

8.7 (47.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.9 (39.0) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

7.0 (44.6) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 58.1 (2.29) |

63.1 (2.48) |

75.0 (2.95) |

87.1 (3.43) |

119.8 (4.72) |

119.4 (4.70) |

136.9 (5.39) |

117.2 (4.61) |

100.1 (3.94) |

91.6 (3.61) |

68.9 (2.71) |

81.7 (3.22) |

1,118.9 (44.05) |

| Average rainy days(≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.8 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 9.6 | 13.0 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 14.7 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 130.1 |

| Averagerelative humidity(%) | 76.8 | 80.1 | 82.1 | 83.1 | 86.5 | 87.7 | 87.7 | 85.0 | 80.7 | 79.7 | 76.1 | 76.6 | 81.8 |

| Mean monthlysunshine hours | 240.3 | 203.4 | 200.8 | 169.3 | 149.1 | 126.1 | 133.9 | 153.7 | 159.0 | 180.5 | 203.8 | 201.9 | 2,121.8 |

| Averageultraviolet index | 12 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 7 |

| Source 1: NIWA Climate Data[66][67] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: MetService[68][69][70] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Henderson North (13km W of Auckland, 7m ASL, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1985–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.8 (89.2) |

34.0 (93.2) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.5 (77.9) |

27.0 (80.6) |

26.0 (78.8) |

28.4 (83.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

34.0 (93.2) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 29.3 (84.7) |

29.3 (84.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.4 (72.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

18.7 (65.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

21.4 (70.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 25.5 (77.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

21.5 (70.7) |

18.7 (65.7) |

16.2 (61.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.3 (70.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.9 (67.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.5 (52.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.4 (59.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

14.8 (58.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.9 (48.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

6.3 (43.3) |

7.9 (46.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.6 (42.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

2.3 (36.1) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

0.2 (32.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

4.4 (39.9) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 70.7 (2.78) |

74.1 (2.92) |

90.7 (3.57) |

110.4 (4.35) |

140.3 (5.52) |

158.5 (6.24) |

178.3 (7.02) |

151.5 (5.96) |

133.0 (5.24) |

103.8 (4.09) |

88.7 (3.49) |

99.4 (3.91) |

1,399.4 (55.09) |

| Source: NIWA[71][72][73] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Ardmore Airport (27km SE of Auckland, 41m ASL, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1969–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.5 (88.7) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

21.9 (71.4) |

22.0 (71.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

28.0 (82.4) |

32.8 (91.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 28.3 (82.9) |

28.5 (83.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

21.7 (71.1) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.7 (80.1) |

29.1 (84.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

23.8 (74.8) |

21.1 (70.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.2 (59.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

18.5 (65.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

19.9 (67.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.0 (66.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 13.2 (55.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

8.1 (46.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

5.4 (41.7) |

5.7 (42.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

9.1 (48.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.6 (54.7) |

9.5 (49.0) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

0.0 (32.0) |

1.3 (34.3) |

3.2 (37.8) |

4.2 (39.6) |

6.6 (43.9) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.1 (41.2) |

3.8 (38.8) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

3.4 (38.1) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 68.2 (2.69) |

66.6 (2.62) |

80.3 (3.16) |

105.4 (4.15) |

123.9 (4.88) |

140.4 (5.53) |

144.0 (5.67) |

136.5 (5.37) |

113.8 (4.48) |

101.7 (4.00) |

88.6 (3.49) |

90.4 (3.56) |

1,259.8 (49.6) |

| Source: NIWA (rain 1990–2016)[74] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for North Shore (Albany) (12km N of Auckland, 64m ASL, 1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

17.9 (64.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.4 (66.9) |

21.3 (70.3) |

19.0 (66.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.1 (66.4) |

19.8 (67.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.0 (60.8) |

13.8 (56.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

11.2 (52.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 15.0 (59.0) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

11.0 (51.7) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 67.0 (2.64) |

65.4 (2.57) |

87.5 (3.44) |

92.6 (3.65) |

118.0 (4.65) |

134.0 (5.28) |

145.4 (5.72) |

125.9 (4.96) |

106.4 (4.19) |

88.8 (3.50) |

70.9 (2.79) |

87.5 (3.44) |

1,189.4 (46.83) |

| Source: NIWA[75] | |||||||||||||

Volcanoes

[edit]

The city of Auckland straddles theAuckland Volcanic Field, an area which in the past, produced at least 53 smallvolcaniccentres over the last ~193,000 years, represented by a range of surface features includingmaars(explosion craters),tuff rings,scoriacones, andlavaflows.[76][77]It is fed entirely bybasalticmagmasourced from themantleat a depth of 70–90 km below the city,[76]and is unrelated to the explosive,subduction-driven volcanism of theTaupō Volcanic Zonein the Central North Island region of Aotearoa, New Zealand, ~250 km away. The Auckland Volcanic Field is considered to be amonogenetic volcanic field, with each volcano erupting only a single time, usually over a timeframe of weeks to years before cessation of activity.[77]Future eruptive activity remains a threat to the city, and will likely occur at a new, unknown location within the field.[76]The most recent activity occurred approximately 1450 AD at theRangitoto Volcano.[76]This event was witnessed byMāorioccupants of the area, making it the only eruption within the Auckland Volcanic Field thus far to have been observed by humans.

The Auckland Volcanic Field has contributed greatly to the growth and prosperity of the Auckland Region since the area was settled by humans. Initially, themaunga(scoria cones) were occupied and established aspā(fortified settlements) by Māori due to the strategic advantage their elevation provided in controlling resources and keyportagesbetween theWaitematāandManukauharbours.[77]The rich volcanic soils found in these areas also proved ideal for the cultivation of crops, such askūmara. Following European arrival, many of the maunga were transformed into quarries to supply the growing city with aggregate and building materials, and as a result were severely damaged or entirely destroyed.[77]A number of the smaller maar craters and tuff rings were also removed during earthworks. Most of the remaining volcanic centres are now preserved within recreational reserves administered byAuckland Council, theDepartment of Conservation, and theTūpuna Maunga o Tāmaki Makaurau Authority.

Demographics

[edit]

The Auckland urban area, as defined by Statistics New Zealand, covers 605.67 km2(233.85 sq mi).[3]The urban area has an estimated population of 1,478,800 as of June 2023, 28.3 percent ofNew Zealand's population. The city has a population larger than the entireSouth Island(1,225,000).[4]

The Auckland urban area had a usual resident population of 1,346,091 at the2018 New Zealand census, an increase of 122,343 people (10.0%) since the2013 census, and an increase of 212,484 people (18.7%) since the2006 census. There were 665,202 males and 680,886 females, giving a sex ratio of 0.977 males per female. Of the total population, 269,367 people (20.0%) were aged up to 15 years, 320,181 (23.8%) were 15 to 29, 605,823 (45.0%) were 30 to 64, and 150,720 (11.2%) were 65 or older.[78]

Culture and identity

[edit]Many ethnic groups, since the late 20th century, have had an increasing presence in Auckland, making it by far the country's mostcosmopolitancity. Historically, Auckland's population has been of majorityEuropeanorigin, though the proportion of those of Asian or other non-European origins has increased in recent decades due to theremoval of restrictions directly or indirectly based on race. Europeans continue to make up the plurality of the city's population, but no longer constitute a majority after decreasing in proportion from 54.6% to 48.1% between the 2013 and 2018 censuses.Asiansnow form the second-largest ethnic group, making up nearly one-third of the population. Auckland is home to the largest ethnicPolynesianpopulation of any city in the world, with a sizeable population ofPacific Islanders(Pasifika) and indigenousMāori people.[9][78]

At the 2018 census, 647,811 people (48.1%) living in the Auckland urban area were European/Pākehā, 424,917 (31.6%) were Asian, 235,086 (17.5%) were Pacific peoples, 154,620 (11.5%) were Māori, 33,672 (2.5%) were Middle Eastern, Latin American and/or African (MELAA), and 13,914 (1.0%) were other ethnicities (totals add to more than 100% since people could identify with multiple ethnicities).[78]

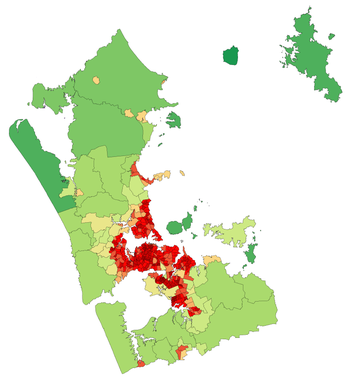

In terms of ethnic distribution, at the2023 censusthe Pasifika population formed the majority in theMāngere-Ōtāhuhu local board areaand the plurality in theŌtara-PapaptoetoeandManurewalocal board areas. The Asian population formed the majority in theHowickandPuketāpapalocal board areas and the plurality in theWhaulocal board area. Europeans formed the plurality in theHenderson-Massey,Maungakiekie-TāmakiandPapakuralocal board areas, and formed the majority in the remaining 11 local board areas. Māori did not form a majority or plurality in any local board area but are in the highest concentrations in the Manurewa and Papakura local board areas.[79]

Immigration to New Zealand is heavily concentrated towards Auckland (partly for job market reasons). This strong focus on Auckland has led the immigration services to award extra points towards immigration visa requirements for people intending to move to other parts of New Zealand.[80]Immigration from overseas into Auckland is partially offset by the net emigration of people from Auckland to other regions of New Zealand.[81]In 2021 and 2022, Auckland recorded its only decreases in population, primarily due to theCOVID-19 pandemicand the associated lack of international migration.[82][83]

At the 2018 Census, 41.6 percent of the Auckland region's population were born overseas; in the local board areas of Upper Harbour, Waitematā, Puketāpapa and Howick, overseas-born residents outnumbered those born in New Zealand.[84]The most common birthplaces of overseas-born residents were mainland China (6.2%), India (4.6%), England (4.4%), Fiji (2.9%), Samoa (2.5%), South Africa (2.4%), Philippines (2.0%), Australia (1.4%), South Korea (1.4%), and Tonga (1.3%).[85]A study from 2016 showed Auckland has the fourth largestforeign-bornpopulation in the world, only behindDubai, Toronto andBrussels, with 39% of its residents born overseas.[86]

Religion

[edit]

Around 48.5 per cent of Aucklanders at the 2013 census affiliated with Christianity and 11.7 per cent affiliated with non-Christian religions, while 37.8 per cent of the population wereirreligiousand 3.8 per cent objected to answering.Roman Catholicismis the largest Christian denomination with 13.3 per cent affiliating, followed byAnglicanism(9.1 per cent) andPresbyterianism(7.4 per cent).[84]

Recent[when?]immigration from Asia has added to the religious diversity of the city, increasing the number of people affiliating withBuddhism,Hinduism,IslamandSikhism, although there are no figures on religious attendance.[87]There is also a small,long-establishedJewish community.[88]

Future growth

[edit]

Auckland is experiencing substantial population growth via immigration (two-thirds of growth) and natural population increases (one-third),[89]and is set to grow to an estimated 1.9 million inhabitants by 2031[90][91]in a medium-variant scenario. This substantial increase in population will have a huge impact on transport, housing and other infrastructure that are, particularly in the case of housing, that are considered to be under pressure already. The high-variant scenario shows the region's population growing to over two million by 2031.[92]

In July 2016, Auckland Council released, as the outcome of a three-year study and public hearings, its Unitary Plan for Auckland. The plan aims to free up to 30 percent more land for housing and allows for greater intensification of the existing urban area, creating 422,000 new dwellings in the next 30 years.[93]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 263,370 | — |

| 1961 | 381,063 | +44.7% |

| 1971 | 548,293 | +43.9% |

| 1981 | 742,786 | +35.5% |

| 1991 | 816,927 | +10.0% |

| 2001 | 991,809 | +21.4% |

| 2006 | 1,074,453 | +8.3% |

| 2013 | 1,415,550 | +31.7% |

| 2018 | 1,571,718 | +11.0% |

| 2023 | 1,656,486 | +5.4% |

| Source:NZ Census | ||

Culture and lifestyle

[edit]|

|

This section needs to be

updated.

(July 2020)

|

Auckland's lifestyle is influenced by the fact that while it is 70 percent rural in land area, 90 percent of Aucklanders live in urban areas.[94]

Positive aspects of Auckland life are its mild climate, plentiful employment and educational opportunities, as well as numerous leisure facilities. Meanwhile, traffic problems, the lack of good public transport, and increasing housing costs have been cited by many Aucklanders as among the strongest negative factors of living there,[95]together with crime that has been rising in recent years.[96]Nonetheless, Auckland ranked third in a survey of the quality of life of 215 major cities of the world (2015 data).[97]

Leisure

[edit]One of Auckland's nicknames, the "City of Sails", is derived from the popularity of sailing in the region.[1]135,000yachtsandlaunchesare registered in Auckland, and around 60,500 of the country's 149,900 registered yachtsmen are from Auckland,[98]with about one in three Auckland households owning a boat.[99]TheViaduct Basin, on the western edge of the CBD, hosted threeAmerica's Cupchallenges (2000 Cup,2003 Cupand2021 Cup).[citation needed]

TheWaitematā Harbouris home to several notable yacht clubs and marinas, including theRoyal New Zealand Yacht SquadronandWesthaven Marina, the largest of theSouthern Hemisphere.[98]The Waitematā Harbour has several swimming beaches, includingMission BayandKohimaramaon the south side of the harbour, and Stanley Bay on the north side. On the eastern coastline of the North Shore, where the Rangitoto Channel divides the inner Hauraki Gulf islands from the mainland, there are popular swimming beaches at Cheltenham and Narrow Neck inDevonport,Takapuna,Milford, and the various beaches further north in the area known as East Coast Bays.[citation needed]

The west coast has popular surf beaches such asPiha,MuriwaiandTe Henga (Bethells Beach). TheWhangaparāoa Peninsula,Orewa,ŌmahaandPākiri, to the north of the main urban area, are also nearby. Many Auckland beaches are patrolled bysurf lifesavingclubs, such asPiha Surf Life Saving Clubthe home ofPiha Rescue. All surf lifesaving clubs are part of theSurf Life Saving Northern Region.[citation needed]

Queen Street,Britomart,Ponsonby Road,Karangahape Road,NewmarketandParnellare major retail areas. Major markets include those held inŌtaraandAvondaleon weekend mornings. A number of shopping centres are located in the middle- and outer-suburbs, withWestfield Newmarket,Sylvia Park,Botany Town CentreandWestfield Albanybeing the largest.[citation needed]

Arts

[edit]A number of arts events are held in Auckland, including theAuckland Festival, the Auckland Triennial, theNew Zealand International Comedy Festival, and theNew Zealand International Film Festival. TheAuckland Philharmoniais the city and region's resident full-time symphony orchestra, performing its own series of concerts and accompanying opera and ballet. Events celebrating the city's cultural diversity include thePasifika Festival, Polyfest, and theAuckland Lantern Festival, all of which are the largest of their kind in New Zealand. Additionally, Auckland regularly hosts theNew Zealand Symphony OrchestraandRoyal New Zealand Ballet. Auckland is part of theUNESCO Creative Cities Networkin the category of music.[100]

Important institutions include theAuckland Art Gallery,Auckland War Memorial Museum,New Zealand Maritime Museum,National Museum of the Royal New Zealand Navy, and theMuseum of Transport and Technology. The Auckland Art Gallery is the largest stand-alone gallery in New Zealand with a collection of over 17,000 artworks, including prominent New Zealand and Pacific Island artists, as well as international painting, sculpture and print collections ranging in date from 1376 to the present day.

In 2009, the Gallery was promised a gift of fifteen works of art by New York art collectors and philanthropistsJulian and Josie Robertson– including well-known paintings byPaul Cézanne,Pablo Picasso,Henri Matisse,Paul GauguinandPiet Mondrian. This is the largest gift ever made to an art museum in Australasia.[101]

Other important art galleries includeMangere Arts Centre,Tautai Pacific Arts Trust,Te Tuhi,Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery,Gow Langsford Gallery, Michael Lett Gallery, Starkwhite, andBergman Gallery.

Parks and nature

[edit]

Auckland Domainis one of the largest parks in the city, it is close to theAuckland CBDand has a good view of theHauraki GulfandRangitoto Island. Smaller parks close to the city centre areAlbert Park,Myers Park,Western ParkandVictoria Park.

While most volcanic cones in theAuckland volcanic fieldhave been affected by quarrying, many of the remaining cones are now within parks, and retain a more natural character than the surrounding city. Prehistoric earthworks and historic fortifications are in several of these parks, includingMaungawhau / Mount Eden,North HeadandMaungakiekie / One Tree Hill.

Other parks around the city are inWestern Springs Reserve, which has a large park bordering theMOTATmuseum and theAuckland Zoo. TheAuckland Botanic Gardensare further south, inManurewa.

Ferries provide transport to parks and nature reserves atDevonport,Waiheke Island, Rangitoto Island andTiritiri Matangi. TheWaitākere RangesRegional Park to the west of Auckland has relatively unspoiledbushterritory, as do theHunua Rangesto the south.

Sport

[edit]Major sporting venues

[edit]Rugby union,cricket,rugby league, association football (soccer) andnetballare widely played and followed. Auckland has a considerable number of rugby union and cricket grounds, and venues for association football, netball, rugby league, basketball, hockey, ice hockey, motorsports, tennis, badminton, swimming, rowing, golf and many other sports.

There are also threeracecourseswithin the city - (Ellerslieand Avondale for thoroughbred racing, andAlexandra Parkforharness racing). A fourth racecourse is located atPukekohe, straddling the boundary between Auckland and the neighbouringWaikatoregion.Greyhound racingis held at Manukau Stadium.

- Eden Parkis the city's primary stadium and a frequent home for internationalrugby unionandcricketmatches, in addition toSuper Rugbymatches where theBluesplay their home games. It is also the home ground ofAucklandin theMitre 10 Cup, andAucklandin domestic cricket.

Eden Parkstadium with statue of Rongomātāne - Mt Smart Stadiumis used mainly forrugby leaguematches and is home to theNew Zealand Warriorsof theNRL, and is also used for concerts, previously hosting the Auckland leg of theBig Day Outmusic festival every January as well as the1990 Commonwealth Games.

- North Harbour Stadiumis mainly used forrugby unionandfootball (soccer)matches, but is also used for concerts. It is the home ground forNorth Harbourin theMitre 10 Cup. In 2019, it became the home field of New Zealand's only professional baseball team,Auckland Tuatara.

- ASB Tennis Centreis Auckland's primary tennis venue, hosting international tournaments for men and women (ASB Classic) in January each year. ASB Bank took over the sponsorship of the men's tournament from 2016, the event formerly being known as theHeineken Open.

- Spark Arena, previously known as Vector Arena, is an indoor auditorium primarily used for concerts and is the home of theNew Zealand Breakersbasketball team. It also hosts internationalnetball.

- Trusts Arenais an indoor venue which primarily hosts netball matches, and is the home of theNorthern Mysticsof theANZ Premiership. It is also where the2007 World Netball Championshipswere held. Since 2015, an annual event on theWorld Series of Dartshas been held there.

- North Shore Events Centreis an indoor arena which is used for a variety of sporting events, as well as concerts and expos. It was formerly home to theNew Zealand Breakersand hosted much of the2009 FIBA Under-19 World Championship.

- Vodafone Events Centreis an indoor arena which hosts a variety of events, and is the home of theNorthern Starsnetball team of theANZ Premiership.

- Pukekohe Park Racewayis a thoroughbred horse-racing venue that used to host a leg of theV8 Supercarsseries annually, along with other motorsports events. The most important horse-racing meeting is held annually at the end of November, featuring the Group 2 Counties Cup and three other stakes races.

- Western Springs Stadiumhas since 1929 hostedspeedway racingduring the summer. It also hosts concerts, with many of New Zealand's largest-ever concerts having taken place at the stadium. It is also the home ofPonsonby RFC.

Major teams

[edit]Sporting teams based in Auckland who compete in national or transnational competitions are as follows:

- Formerly Auckland Blues, theBluescompete inSuper Rugby. Auckland is also home to threeMitre 10 Cuprugby union teams:Auckland,North HarbourandCounties Manukau.

- Previously Auckland Warriors, theNew Zealand Warriorsare a team in Australia'sNational Rugby Leaguecompetition. They play their home games atMt Smart Stadium. TheAkarana FalconsandCounties Manukaucompete in theNational Competition.

- Auckland's men's first class cricket team, theAuckland Aces, play their home matches atEden Park, generally on the outer oval. The women's team, theAuckland Hearts, play at Melville Park inEpsom.

- Auckland FCare a professional football club that will compete in theA-League MenandA-League Womencompetitions. The football club will play their home games atMt Smart Stadium.

- Auckland City,Auckland United, andEastern Suburbsare football teams play in theNorthern League.

- Northern MysticsandNorthern Starsare netball teams who compete in theANZ Premiership. The Mystics play their home games atTrusts Stadiumand the Stars at theVodafone Events Centre.

- New Zealand Breakersare a basketball team who compete in theAustralian National Basketball Leagueand play their home games primarily atSpark Arena. TheAuckland TuataraandFranklin Bullsplay in theNew Zealand National Basketball League.

- Botany SwarmandWest Auckland Admiralscompete in theNew Zealand Ice Hockey League.

- Auckland Tuatarahad previously competed in theAustralian Baseball League.

Major events

[edit]Annual sporting events held in Auckland include:

- TheATP Auckland Openand theWTA Auckland Open(both known for sponsorship reasons as the ASB Classic), are men's and women's tennis tournaments, respectively, which are held annually at theASB Tennis Centrein January. The men's tournament has been held since 1956, and the women's tournament since 1986.

- TheAuckland Super400(known for sponsorship reasons as the ITM Auckland Super 400) was aSupercars Championshiprace held atPukekohe Park Raceway. The race has been held intermittently since 1996

- TheAuckland Marathon(and half-marathon) is an annualmarathon. It is the largest marathon in New Zealand and draws in the vicinity of 15,000 entrants. It has been held annually since 1992.

- TheAuckland Anniversary Regattais a sailing regatta which has been held annually since 1840, the year of Auckland's founding. It is held overAuckland Anniversaryweekend and attracts several hundred entrants each year. It is the largest such regatta, and the oldest sporting event, in New Zealand.

- Auckland Cup Weekis an annualhorse racingcarnival, which has been held in early March since its inception in 2006. It is the richest such carnival in New Zealand, and incorporates several of New Zealand's major thoroughbred horse races, including theAuckland Cup, held since 1874, andNew Zealand Derby, held since 1875.

- TheAuckland Harbour Crossing Swimis an annual summer swimming event. The swim crosses theWaitematā Harbour, from the North Shore to theViaduct Basincovering 2.8 km (often with some considerable counter-currents). The event has been held since 2004 and attracts over a thousand mostly amateur entrants each year, making it New Zealand's largest ocean swim.[102]

- Round the Bays is an annualfun-run. The course travels eastwards along the Auckland waterfront, with the run starting in theCBDand ending inSt Heliers, the total length being 8.4 km (5.2 mi). It is the largest fun-run in New Zealand and attracts tens of thousands of entrants each year, with the number of entrants reported to have peaked at 80,000 in 1982. It has been held annually since1972.[103]

Major events previously held in Auckland include the1950 British Empire Gamesand theCommonwealth Games in 1990,[104]and a number of matches (including the semi-finals and the final) of the1987 Rugby World Cupand2011 Rugby World Cup.[105]Auckland hosted theAmerica's CupandLouis Vuitton Cupin 2000, 2003, and 2021. The2007 World Netball Championshipswere held at theTrusts Stadium. TheITU World Triathlon Seriesheld a Grand Final event in theAuckland CBDfrom 2012 until 2015.[106]TheNRL Auckland Nineswas arugby league ninespreseason competition played atEden Parkfrom 2014 to 2017. The 2017World Masters Gameswere held at a number of venues around Auckland.[107]The Auckland Darts Masters was held annually atThe Trusts Arenafrom 2015 to 2018.

Architecture

[edit]

|

This section

needs expansion. You can help by

adding to it.

(August 2019)

|

Auckland comprises a diversity of architectural styles owing to its early beginnings as a settlement, to theVictorianera right through to the contemporary era of the late 20th century. The city has legislation in effect to protect the remaining heritage, with the key piece of legislation being the Resource Management Act of 1991.[108]Prepared under this legislation is the Auckland Unitary Plan, which indicates how land can be used or developed. Prominent historic buildings in Auckland include theDilworth Building, theAuckland Ferry Terminal, Guardian Trust Building, Old Customs House, Landmark House, theAuckland Town Halland theBritomart Transport Centre–many of these are located on the main thoroughfare of Queen Street.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]|

|

This section has multiple issues.Please help

improve itor discuss these issues on the

talk page.

(Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Auckland is the major economic and financial centre of New Zealand. It has an advancedmarket economywith strengths in finance, commerce, and tourism. Most major international corporations have an Auckland office; the most expensive office space is around lowerQueen Streetand theViaduct Basinin theAuckland CBD, where many financial and business services are located, which constitute a large percentage of the CBD economy.[109]The largest commercial and industrial areas of the Auckland Region are Auckland CBD and the western parts ofManukau, mostly bordering theManukau Harbourand theTamaki Riverestuary.

Auckland is classified by theGlobalization and World Cities Research Networkas a Beta +World City[110]because of its importance in commerce,the arts, and education.

According to the 2013 census, the primary employment industries of Auckland residents are professional, scientific and technical services (11.4 percent), manufacturing (9.9 percent), retail trade (9.7 percent), health care and social assistance (9.1 percent), and education and training (8.3 percent). Manufacturing is the largest employer in the Henderson-Massey, Howick, Māngere-Ōtāhuhu, Ōtara-Papatoetoe, Manurewa and Papakura local board areas, retail trade is the largest employer in the Whau local board area, while professional, scientific and technical services are the largest employer in the remaining urban local board areas.[111]

The sub-national GDP of the Auckland region was estimated at NZ$122 billion in 2022, almost 40 percent of New Zealand's national GDP.[112]The per-capita GDP of Auckland was estimated at $71,978, the third-highest in the country after the Taranaki and Wellington regions, and above the national average of $62,705.[113]

In 2014, the median personal income (for all persons older than 15 years of age, per year) in Auckland was estimated at $41,860, behind only Wellington.[114]

Housing

[edit]

Housing varies considerably between some suburbs havingstate owned housingin the lower income neighbourhoods, to palatial waterfront estates, especially in areas close to theWaitematā Harbour. Traditionally, the most common residence of Aucklanders was a standalone dwelling on a 'quarter acre' (1,000 m2).[90]However, subdividing such properties with 'infill housing' has long been the norm. Auckland's housing stock has become more diverse in recent decades, with many more apartments being built since the 1970s, particularly since the 1990s in the CBD.[115]Nevertheless, the majority of Aucklanders live in single dwelling housing and are expected to continue to do so, even with most of future urban growth being through intensification.[90]

Auckland's housing is amongst the least affordable in the world, based on comparing average house prices with average household income levels[116][117]and house prices have grown way well above the rate of inflation in recent decades.[115]In August 2022, the Real Estate Institute of New Zealand (REINZ) reported the median house price in the Auckland region was $1,100,000, ranging from $900,000 in the former Papakura District area to $1,285,000 in the former North Shore City area, This is compared to a median price of $700,000 outside of Auckland.[118]There is significant public debate around why Auckland's housing is so expensive, often referring to a lack of land supply,[115]the easy availability of credit for residential investment[119]and Auckland's high level of liveability.

In some areas, the Victorianvillashave been torn down to make way for redevelopment. The demolition of the older houses is being combated through increased heritage protection for older parts of the city.[120]Auckland has been described as having 'the most extensive range of timbered housing with its classical details and mouldings in the world', many of them built in the Victorian and Edwardian eras.[121]

Housing crisis

[edit]In the lead-up to 2010, a housing crisis began in Auckland, with the market not being able to sustain the demand for affordable homes. The Housing Accords and Special Housing Areas Act 2013 mandated that a minimum of 10 percent of new builds in certain housing areas be subsidised to make them affordable for buyers who had incomes on par with the national average. In a new subdivision atHobsonville Point, 20 percent of new homes were reduced to below $550,000.[122]Some of the demand for new housing at this time was attributed to the 43,000 people who moved into Auckland between June 2014 and June 2015.[89]Research has found that Auckland is set to become even more densely populated in future which could ease the burden by creating higher density housing in the city centre.[123][124]From around November 2021 to May 2022, house prices dropped 11.68%.[125]It has continued to fall since due to inflation, bank interest rates, and a variety of other factors.[126][127][128][129]

Government

[edit]Local

[edit]

The Auckland Council is thelocal authoritywith jurisdiction over the city of Auckland, along with surrounding rural areas, parkland, and the islands of the Hauraki Gulf.[130]

From 1989 to 2010, Auckland was governed by several city and district councils, with regional oversight byAuckland Regional Council. In the late 2000s, New Zealand's central government and parts of Auckland's society felt that this large number of councils, and the lack of strong regional government (with the Auckland Regional Council having only limited powers), were hindering Auckland's progress.[citation needed]

ARoyal Commission on Auckland Governancewas set up in 2007;[131][132]in 2009, it recommended a unified local governance structure for Auckland by amalgamating the councils.[133]The government subsequently announced that a "super city" would be set up with a single mayor by the time of New Zealand's local body elections in 2010.[134][135]

In October 2010,Manukau CitymayorLen Brownwas elected mayor of the amalgamatedAuckland Council. He was re-elected for a second term in October 2013. Brown did not stand for re-election in the2016 mayoral election, and was succeeded by successful candidatePhil Goffin October 2016.[136]Twenty councillors comprise the remainder of the Auckland Council governing body, elected from thirteen electoral wards.

National

[edit]

Between 1842 and 1865, Auckland was the capital city of New Zealand.[137]Parliament met in what is nowOld Government Houseon theUniversity of Auckland's City campus. The capital was moved to the more centrally locatedWellingtonin 1865.[citation needed]

Auckland, because of its large population, is covered by 23 general electorates and threeMāori electorates,[138]each returning one member to theNew Zealand House of Representatives. TheNational Partyholds 14 general electorates, theLabour Partysix,ACTtwo and theGreensone. The three Māori electorates are held byTe Pāti Māori.

Other

[edit]The administrative offices of theGovernment of the Pitcairn Islandsare situated in Auckland.[139]

Education

[edit]

Primary and secondary

[edit]The Auckland urban area has 340 primary schools, 80 secondary schools, and 29 composite (primary/secondary combined) schools as of February 2012, catering for nearly a quarter of a million students. The majority are state schools, but 63 schools are state-integrated and 39 are private.[141]

The city is home to some of the largest schools in terms of students in New Zealand, includingMt Albert Grammar School, the second-largest school in New Zealand with a student population of 3035,[142]andRangitoto Collegein the East Coast Bays area, the largest school in New Zealand with 3,696 students as of February 2024.[143]

Tertiary

[edit]Auckland has some of the largest universities in the country. Five of New Zealand's eight universities have campuses in Auckland, as well as eight of New Zealand's fifteen polytechnics. TheUniversity of Auckland,Auckland University of Technology,Manukau Institute of Technology, andUnitec Institute of Technologyare all based in Auckland. Despite being based in other regions, theUniversity of Otago,Victoria University of Wellington,Massey University, and several polytechnics have satellite campuses in Auckland.[144]

Auckland is a major centre of overseas language education, with large numbers of foreign students (particularly East Asians) coming to the city for several months or years to learn English or study at universities – although numbers New Zealand-wide have dropped substantially since peaking in 2003.[145]As of 2007[update], there are around 50New Zealand Qualifications Authority(NZQA) certified schools and institutes teaching English in the Auckland area.[146]

Transport

[edit]

TheState Highway networkconnects the different parts of Auckland, withState Highway 1being the major north–south thoroughfare through the city (including both theNorthernandSouthern Motorways) and the main connection to the adjoining regions ofNorthlandandWaikato. TheNorthern Buswayruns alongside part of the Northern Motorway on the North Shore. Other state highways within Auckland includeState Highway 16(the Northwest Motorway),State Highway 18(the Upper Harbour Motorway) andState Highway 20(the Southwest Motorway).State Highway 22is a non-motorway rural arterial connectingPukekoheto the Southern Motorway atDrury.[147]

TheAuckland Harbour Bridge, opened in 1959, is the main connection between theNorth Shoreand the rest of the Auckland region.[148]The bridge provides eight lanes of vehicle traffic and has a moveable median barrier for lane flexibility, but does not provide access for rail, pedestrians or cyclists. TheCentral Motorway Junction, also called 'Spaghetti Junction' for its complexity, is the intersection between the two major motorways of Auckland (State Highway 1 and State Highway 16).[149]

Two of the longest arterial roads within the Auckland Region areGreat North RoadandGreat South Road– the main connections in those directions before the construction of the State Highway network.[147]Numerous arterial roads also provide regional and sub-regional connectivity, with many of these roads (especially on the isthmus) previously used to operate Auckland'sformer tram network.

Auckland has four railway lines (Western,Onehunga,EasternandSouthern). These lines serve the western, southern and eastern parts of Auckland from theWaitematā railway stationin downtown Auckland, the terminal station for all lines, where connections are also available to ferry and bus services. Work began in late 2015 to provide more route flexibility and connect Britomart, now named Waitematā, more directly to the western suburbs on the Western Line via an underground rail tunnel known as theCity Rail Linkproject. Alight rail networkis also planned.

Travel modes

[edit]- Road and rail

Private vehicles are the main form of transportation within Auckland, with around seven percent of journeys in the Auckland region undertaken by bus in 2006,[150]and two percent undertaken by train and ferry.[150]For trips to the city centre at peak times, the use of public transport is much higher, with more than half of trips undertaken by bus, train or ferry.[151]In 2010, Auckland ranked quite low in its use of public transport, having only 46 public transport trips per capita per year,[151][152]while Wellington has almost twice this number at 91, and Sydney has 114 trips.[153]This strong dependence on roads results in substantialtraffic congestionduring peak times.[154]This car reliance means 56% of the city's energy usage goes towards transportation, and CO2emissions will increase by 20% in the next 10 years.[124]

Bus services in Auckland are mostly radial, with few cross-town routes. Late-night services (i.e. past midnight) are limited, even on weekends. A major overhaul of Auckland's bus services was implemented during 2016–18, significantly expanding the reach of frequent bus services: those that operate at least every 15 minutes during the day and early evening, every day of the week.[155]Auckland is connected with other cities through bus services operated byInterCity.

Rail services operate along four lines between the CBD and the west, south and south-east of Auckland, with longer-distance trains operating to Wellington only a few times each week.[156]Following the opening ofWaitematā railway stationin 2003, major investment in Auckland's rail network occurred, involving station upgrades, rolling stock refurbishment and infrastructure improvements.[157]The rail upgrade has includedelectrification of Auckland's rail network, with electric trains constructed byConstrucciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarrilescommencing service in April 2014.[158]A number of proposed projects to further extend Auckland's rail network were included in the 2012 Auckland Plan, including theCity Rail Link, theAuckland Airport Line, theAvondale-Southdown Lineand rail to theNorth Shore.[citation needed]

- Other modes

Auckland's portsare the second largest in the country, behind thePort of Tauranga,[159]and a large part of both inbound and outbound New Zealand commerce travels through them, mostly via the facilities northeast of Auckland CBD. Freight usually arrives at or is distributed from the port via road, though the port facilities also have rail access. Auckland is a major cruise ship stopover point, with the ships usually tying up atPrinces Wharf. Auckland CBD is connected to the coastal suburbs, to the North Shore and to outlying islands by ferry.[citation needed]

- Air

Auckland has various small regional airports andAuckland Airport, the busiest in the country. Auckland Airport, New Zealand's largest, is in the southern suburb of Māngere on the shores of the Manukau Harbour. There are frequent services to Australia, and to other New Zealand destinations. There are also direct connections to many locations in the South Pacific, as well as the United States, China, Asia,Vancouver, London,SantiagoandBuenos Aires.[160]In terms of international flights, Auckland is the second-best connected city in Oceania.[161]

- Policies

Research atGriffith Universityhas indicated that from the 1950s to the 1980s, Auckland engaged in some of the most pro-automobile transport policies anywhere in the world.[162]With public transport declining heavily during the second half of the 20th century (a trend mirrored in most Western countries, such as the US),[163]and increased spending on roads and cars, New Zealand (and specifically Auckland) now has the second-highest vehicle ownership rate in the world, with around 578 vehicles per 1000 people.[164]Auckland has also been called a very pedestrian- and cyclist-unfriendly city, though some efforts are being made to change this,[165]with Auckland being a major participant in the government's "Urban Cycleways" initiative, and with the "SkyPath" project for a walk and cycleway on the Auckland Harbour Bridge having received Council support, and planning consent.[166][167]

Infrastructure and services

[edit]Electricity

[edit]

Vectorowns and operates the majority of the distribution network in urban Auckland,[168]with Counties Energy owning and operating the network south of central Papakura.[169]The city is supplied fromTranspower's national grid from thirteen substations across the city. There are no major electricity generation stations located within the city or north of Auckland, so almost all of the electricity for Auckland and Northland must be transmitted from power stations in the south, mainly fromHuntly Power Stationand theWaikato Riverhydroelectric stations. The city had two natural gas-fired power stations (the 404 MWŌtāhuhu Band the 175 MWSouthdown), but both shut down in 2015.[170][171]

There have been several notable power outages in Auckland.[172]The five-week-long1998 Auckland power crisisblacked out much of the CBD after a cascade failure occurred on the four main underground cables supplying the CBD.[173]The2006 Auckland Blackoutinterrupted supply to the CBD and many inner suburbs after an earth wire shackle at Transpower's Otāhuhu substation broke and short-circuited the lines supplying the inner city.

In 2009, much of the northern and western suburbs, as well as all ofNorthland, experienced a blackout when a forklift accidentally came into contact with the Ōtāhuhu to Henderson 220 kV line, the only major line supplying the region.[174]Transpower spent $1.25 billion in the early 2010s reinforcing the supply into and across Auckland, including a400 kV-capable transmission linefrom the Waikato River to Brownhill substation (operating initially at 220 kV), and 220 kV underground cables between Brownhill and Pakuranga, and betweenPakuranga and Albany via the CBD. These reduced the Auckland Region's reliance on Ōtāhuhu substation and northern and western Auckland's reliance on the Ōtāhuhu to Henderson line.[citation needed]

Natural gas

[edit]Auckland was one of the original nine towns and cities in New Zealand to be supplied with natural gas when theKapuni gas fieldentered production in 1970 and a 340 km long high-pressure pipeline from the field in Taranaki to the city was completed. Auckland was connected to theMaui gas fieldin 1982 following the completion of a high-pressure pipeline from the Maui gas pipeline nearHuntly, via the city, to Whangārei in Northland.[175]

The high-pressure transmission pipelines supplying the city are now owned and operated byFirst Gas, withVectorowning and operating the medium and low-pressure distribution pipelines in the city.[citation needed]

Tourism

[edit]Before theCOVID-19 pandemic, Auckland-related tourism boosted the New Zealand economy.[176]Many tourists visiting New Zealand would arrive viaAuckland Airport, andcruise shipsalso called.

Tourist attractions and landmarks in Auckland include:

- Attractions and buildings

- Aotea Square– a main square in the CBD, adjacent to Queen Street, theAotea Centreand theAuckland Town Hall.

- Auckland Art Gallery– the city's mainart gallery.

- Auckland Civic Theatre– an internationally significantatmospheric theatrebuilt in 1929. It was renovated in 2000 to its original condition.

- Auckland Harbour Bridge– a bridge which spans the Waitematā Harbour. It connects central Auckland and theNorth Shore, and is regarded as an iconic symbol of Auckland.

- Auckland Town Hall– the city'stown hall. Originally built for theAuckland City Councilin 1911, it is now the ceremonial headquarters of theAuckland Council. The hall has a theatre which is known for the quality of its acoustics, and is regularly used for concerts and other live performances.

- Auckland War Memorial Museum– a large multi-exhibition museum in theAuckland Domainin theneo-classicalstyle. It was built in 1929.

- Auckland Zoo– the city's mainzoo, located atWestern Springs.

- Aotea Centre– a civic centre which was completed in 1989. It hosts exhibitions, concerts and other live performances.

- Britomart Transport Centre– the main public transport centre in the CBD. It is an Edwardian building which was formerly the city's Chief Post Office.

- Eden Park– the city's primary stadium and a frequent host of international rugby union and cricket matches. It hosted the 1987 and 2011 Rugby World Cup finals.[177]

- Howick Historical Village– a recreated New Zealand colonial village operating as a living museum.

- Karangahape Road– colloquially known as "K' Road", a street at the southern end of the CBD, adjacent to the suburb ofNewton. It is now known locally for cafes and restaurants, bars, pubs, music venues and shops. Historically it was Auckland'sred-light district.

- Kelly Tarlton's Sea Life Aquarium– an aquarium and Antarctic environment in the eastern suburb ofMission Bay, built in a set of former sewage-storage tanks. It showcases a wide variety of marine animals.

- Museum of Transport and Technology (MOTAT)– a transport and technology museum atWestern Springs.

- New Zealand Maritime Museum– a museum which features exhibitions and collections relating to New Zealand maritime history. It is located at Hobson Wharf, adjacent to theViaduct Harbour.

- Ponsonby– a suburb to the west of central Auckland, known for its range of independent cafes, restaurants, shops and extensive collection of Victorian and Edwardian housing.

- Queen Street– the main commercial thoroughfare of the CBD, running from Karangahape Road downhill to the harbour.

- Rainbow's End– an amusement park with over 20 rides and attractions located adjacent to the Manukau CBD.

- St Patrick's Cathedral– the Catholic Cathedral of Auckland. It is a 19th-century Gothic building, which was renovated from 2003 to 2007 for refurbishment and structural support.

- Sky Tower– the second tallest free-standing structure in the Southern Hemisphere. It is 328 m (1,076 ft).

- Spark Arena– events centre in central Auckland completed in 2007. Holding 12,000 people, it is used for sporting events and concerts.

- Stardome Observatory and Planetarium– a public astronomical observatory situated in the grounds ofMaungakiekie / One Tree Hill.

- Viaduct Harbour– formerly an industrial harbour, the basin was re-developed as a marina and residential area in the 1990s. It served as a base for the America's Cup regattas in 2000 and 2003.

- Natural landmarks

- Auckland Domain– built atop the tuff ring of the Pukekawa volcano in 1843, the domain is the oldest and one of the largest parks in the city. Located at the intersection of the suburbs ofParnell,Newmarket, andGrafton, it is close to the CBD and offers a clear view of the harbour and of Rangitoto Island.Auckland War Memorial Museumis located at the highest point in the park.

- Coast to Coast Walkway – a 16 km walk through and past many of Auckland's natural landmarks and attractions, joining the east and west coasts of Auckland.[178]

- Great Barrier Island– the largest island in the Hauraki Gulf, located 100 km (62 mi) north-east of the Auckland CBD. The island has a population of approximately 1,000 people and is entirely off-grid, relying on renewable solar power and collection of freshwater.[179]

- Maungawhau / Mount Eden– avolcanic conewith a grassycrater. The highest natural point on the Auckland isthmus, it offers 360-degree views of the city and is thus a popular tourist outlook.

- Maungakiekie / One Tree Hill– a volcanic cone that dominates the skyline of the southern inner suburbs. It no longer has a tree on the summit (after a politically motivated attack on the erstwhile tree) but is crowned by anobelisk.

- Rangitoto Island– an island which guards the entrance toWaitematā Harbourand forms a prominent feature on the eastern horizon. The island was formed by a volcanic eruption approximately 600 years ago, making it both the youngest and the largest volcano in theAuckland Volcanic Field. The island reaches a height of 260 m, and offers panoramic views across Auckland.

- Takarunga / Mount VictoriaandMaungauika (North Head)– nearby volcanic cones inDevonport, both of which offer views of theWaitematā Harbourand CBD. Both hills were fortified[why?]with artillery and bunkers in the late 19th century and were maintained as coastal defences until the 1950s.

- Tiritiri Matangi Island- an island in theHauraki Gulflocated 30 km (19 mi) northeast of the Auckland CBD. The island is an open nature-reserve which is managed under the supervision of theDepartment of Conservation. It is specifically noted for its bird life, includingtakahē, North Islandkōkakoandkiwi.

- Waiheke Island– the second-largest island in theHauraki Gulf, located 21.5 km (13.4 mi) east of the Auckland CBD. It is known for its beaches, forests, vineyards and olive groves.

- TheWaitākere Ranges, a range of hills approximately 25 km (16 mi) west of the CBD. The hills run from north to south along the west coast of theNorth Islandfor approximately 25 km (16 mi), and rise to a peak of 474 metres (1,555 ft). A significant portion of the hills lie within a regional park, which includes numerous bush-walking tracks. Coastal cliffs rise to 300 metres (980 ft), intermittently broken up by beaches; popular surf beaches in the area includePiha,Muriwai,Te Henga (Bethells Beach)andKarekare.

Cultural references

[edit]- Advocates of the city sometimes like to quoteRudyard Kipling's invocation its remoteness: "Last, loneliest, loveliest, exquisite, apart", from his poem "The Song of the Cities" (1893).[180]

- Different works ofRobert Heinleinrefer to a fictional human colony onVenusas "New Auckland".[181]

Notable people

[edit]International relationships

[edit]Auckland Council engages internationally through formal sister city relationships, strategic alliances and cooperation arrangements with other cities and countries, and participation in international city networks and forums. Auckland Council maintainsrelationshipswith the following cities and countries.[182][183]

Sister cities

[edit]- Los Angeles, United States (1971)

- Utsunomiya, Japan (1982)

- Fukuoka, Japan (1986)

- Brisbane, Australia (1988)

- Guangzhou, China (1989)[184]

- Kakogawa, Japan (1992)

- Busan, South Korea (1996)

- Taichung, Taiwan (1996)

- Ningbo, China (1998)

- Qingdao, China (2008)

Friendship and Cooperation cities

[edit]- Tomioka, Japan (1983)

- Shinagawa, Japan (1993)

- Galway, Ireland (2002)

- Nadi, Fiji (2006)

- Hamburg, Germany (2007)

- Pohang, South Korea (2008)

- Shanghai, China (2012)

Cooperation countries

[edit]- Cook Islands(2012)

- Samoa(2012)

- Tonga(2012)

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^abIhaka, James (13 October 2006)."Punters love City of Sails - National - NZ Herald News".The New Zealand Herald.Archivedfrom the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved20 May2017.

- ^Rawlings-Way, Charles; Atkinson, Brett (2010).New Zealand(15th ed.). Footscray, Vic.: Lonely Planet. p. 125.ISBN978-1742203645. Retrieved6 October2020.

- ^abc"ArcGIS Web Application".statsnz.maps.arcgis.com.Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved25 April2024.

- ^abcde"Subnational population estimates (RC, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)".Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved25 October2023.(regional councils);"Subnational population estimates (TA, SA2), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)".Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved25 October2023.(territorial authorities);"Subnational population estimates (urban rural), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996-2023 (2023 boundaries)".Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved25 October2023.(urban areas)

- ^"Quarterly Economic Monitor | Auckland | Gross domestic product".Archivedfrom the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved1 July2022.

- ^Deverson, Tony; Kennedy, Graeme, eds. (2005)."Auckland".The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary.Oxford University Press.doi:10.1093/acref/9780195584516.001.0001.ISBN978-0-19-558451-6.Archivedfrom the original on 21 November 2022. Retrieved21 November2022.

- ^"New Zealand's population reflects growing diversity | Stats NZ".www.stats.govt.nz.Archivedfrom the original on 11 August 2023. Retrieved17 November2021.

- ^Peacock, Alice (17 January 2016)."Auckland a melting pot - ranked world's fourth most cosmopolitan city".Stuff.Archivedfrom the original on 21 October 2022. Retrieved31 July2023.

- ^ab"Auckland and around".Rough Guideto New Zealand, Fifth Edition. Archived fromthe originalon 27 February 2008. Retrieved16 February2010.

- ^"About Auckland".The Auckland Plan 2050.Archivedfrom the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved3 January2019.

- ^"tamaki - Te Aka Māori Dictionary".tamaki - Te Aka Māori Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved1 April2024.

- ^Ferdinand von Hochstetter(1867).New Zealand. p. 243.Archivedfrom the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved19 June2008.

- ^Margaret McClure, Auckland region,http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/auckland-regionArchived5 November 2013 at theWayback Machine

- ^"Tallest building in southern hemisphere approved".ABC News. 18 March 2013.Archivedfrom the original on 24 December 2022. Retrieved4 May2022.

- ^"Auckland among world's most expensive cities".The New Zealand Herald. 31 December 2016.Archivedfrom the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved29 August2017.

- ^"Global Liveability Index 2021".The Economist.Archivedfrom the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved9 June2021.

- ^"Best UK cities revealed in Mercer's quality of life rankings for 2019".Evening Standard. 13 March 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved31 May2019.

- ^"Quality of Living City Ranking".Mercer. 2019.Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved31 May2019.

- ^Mackintosh, Lucy (2021).Shifting Grounds: Deep Histories of Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland.Bridget Williams Books. p. 125.ISBN978-1-988587-33-2.

- ^abTaonui, Rāwiri (8 February 2005)."The tribes of Tāmaki".Te Ara.Archivedfrom the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved17 March2021.

- ^Te Ākitai Waiohua(24 August 2010)."CULTURAL VALUES ASSESSMENT BY TE ĀKITAI WAIOHUA for MATUKUTŪREIA QUARRY PRIVATE PLAN CHANGE"(PDF). Auckland Council. Retrieved4 February2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^"ca 1720".Manukau's Journey - Ngā Tapuwae o Manukau. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections. MJ_0015.Archivedfrom the original on 4 July 2021. Retrieved17 March2021.

- ^Fox, Aileen(1977)."Pa of the Auckland Isthmus: An Archaeological Analysis".Records of the Auckland Institute and Museum.14: 1–24.ISSN0067-0464.JSTOR42906245.WikidataQ58677038.

- ^Ferdinand von Hochstetter(1867).New Zealand. p. 243.Archivedfrom the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved19 June2008.

- ^Sarah Bulmer."City without a state? Urbanisation in pre-European Taamaki-makau-rau (Auckland, New Zealand)"(PDF). Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 9 June 2007. Retrieved3 October2007.

- ^"Ngāti Whātua – European contact".Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.Archivedfrom the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved3 October2007.

- ^Michael King(2003).The Penguin History of New Zealand. Auckland, N.Z.: Penguin Books. p. 135.ISBN0-14-301867-1.

- ^"Āpihai Te Kawau".New Zealand History. NZ Government.Archivedfrom the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved27 June2021.

- ^"Apihai Te Kawau". Ngāti Whātua-o-Ōrākei.Archivedfrom the original on 11 August 2019. Retrieved11 August2019.

- ^"Cultural Values Assessment in Support of the Notices of Requirement for the Proposed City Rail Link Project"(PDF). Auckland Transport. pp. 14–16.Archived(PDF)from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved3 May2021.

- ^Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Orakei Claim(PDF)(Report) (1991 ed.). Wellington, New Zealand: The Waitangi Tribunal. November 1987. p. 23.ISBN0-86472-084-X.Archived(PDF)from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved5 May2021.

- ^Social and Economic Research and Monitoring team (2010).Brief history of Auckland's urban form. Auckland Regional Council.ISBN978-1-877540-57-8.

- ^Stone, R. C. J.(2001).From Tamaki-makau-rau to Auckland. Auckland University Press.ISBN1869402596.

- ^McKinnon, Malcolm (ed.)."Colonial and provincial government - Julius Vogel and the abolition of provincial government".Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.Archivedfrom the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved20 October2021.

- ^"The long lost diorama of Auckland which reveals the city of 1939".thespinoff.co.nz. 25 March 2018.Archivedfrom the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved17 March2019.

- ^"Slide to war - The Treaty in practice | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". Nzhistory.net.nz.Archivedfrom the original on 24 October 2016. Retrieved20 September2017.

- ^abO'Malley, Vincent (6 December 2016)."'The great war for NZ broke out less than 50 km from Queen St': Vincent O'Malley on the Waikato War and the making of Auckland (".Spinoff.Archivedfrom the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved30 December2016.

- ^The Aotearoa History Show Episode 4 - Te Tiriti o Waitangi. YouTube,RNZ&NZ on Air. 14 October 2019. Event occurs at 4:50 to 5:10.Archivedfrom the original on 8 April 2024. Retrieved13 April2024.

- ^Plan 2050, Auckland."What Manakau will look like in the future".aucklandcouncil.govt.nz.Archivedfrom the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved17 November2021.