Medicine

Medicineis thescience[1]andpractice[2]of caring for patients, managing thediagnosis,prognosis,prevention,treatment,palliationof theirinjuryordisease, andpromoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety ofhealth carepractices evolved to maintain and restorehealthby thepreventionand treatment ofillness. Contemporary medicine appliesbiomedical sciences,biomedical research,genetics, andmedical technologytodiagnose, treat, and prevent injury and disease, typically throughpharmaceuticalsorsurgery, but also through therapies as diverse aspsychotherapy,external splints and traction,medical devices,biologics, andionizing radiation, amongst others.[3]

Medicine has been practiced sinceprehistoric times, and for most of this time it was anart(an area of creativity and skill), frequently having connections to thereligiousandphilosophicalbeliefs of local culture. For example, amedicine manwould applyherbsand sayprayersfor healing, or an ancientphilosopherandphysicianwould applybloodlettingaccording to the theories ofhumorism. In recent centuries, since theadvent of modern science, most medicine has become a combination of art and science (bothbasicandapplied, under theumbrellaofmedical science). For example, while stitching technique forsuturesis an art learned through practice, knowledge of what happens at thecellularandmolecularlevel in the tissues being stitched arises through science.

Prescientific forms of medicine, now known astraditional medicineorfolk medicine, remain commonly used in the absence of scientific medicine and are thus calledalternative medicine. Alternative treatments outside of scientific medicine with ethical, safety and efficacy concerns are termedquackery.

Etymology

[edit]Medicine (UK:/ˈmɛdsɪn/,US:/ˈmɛdɪsɪn/) is the science and practice of thediagnosis,prognosis,treatment, andpreventionofdisease.[4][5]The word "medicine" is derived fromLatinmedicus, meaning "a physician".[6][7]

Clinical practice

[edit]

Medical availability and clinical practice vary across the world due to regional differences incultureandtechnology. Modern scientific medicine is highly developed in theWestern world, while indeveloping countriessuch as parts of Africa or Asia, the population may rely more heavily ontraditional medicinewith limited evidence and efficacy and no required formal training for practitioners.[8]

In thedeveloped world,evidence-based medicineis not universally used in clinical practice; for example, a 2007 survey of literature reviews found that about 49% of the interventions lacked sufficient evidence to support either benefit or harm.[9]

In modern clinical practice,physiciansandphysician assistantspersonally assess patients todiagnose, prognose, treat, and prevent disease using clinical judgment. Thedoctor-patient relationshiptypically begins with an interaction with an examination of the patient'smedical historyandmedical record, followed by a medical interview[10]and aphysical examination. Basic diagnosticmedical devices(e.g.,stethoscope,tongue depressor) are typically used. After examining forsignsand interviewing forsymptoms, the doctor may ordermedical tests(e.g.,blood tests), take abiopsy, or prescribepharmaceutical drugsor other therapies.Differential diagnosismethods help to rule out conditions based on the information provided. During the encounter, properly informing the patient of all relevant facts is an important part of the relationship and the development of trust. The medical encounter is then documented in the medical record, which is a legal document in many jurisdictions.[11]Follow-ups may be shorter but follow the same general procedure, and specialists follow a similar process. The diagnosis and treatment may take only a few minutes or a few weeks, depending on the complexity of the issue.

The components of the medical interview[10]and encounter are:

- Chief complaint (CC): the reason for the current medical visit. These are thesymptoms. They are in the patient's own words and are recorded along with the duration of each one. Also calledchief concernorpresenting complaint.

- Current activity: occupation, hobbies, what the patient actually does.

- Family history(FH): listing of diseases in the family that may impact the patient. Afamily treeis sometimes used.

- History of presentillness(HPI): the chronological order of events of symptoms and further clarification of each symptom. Distinguishable from history of previous illness, often called past medical history (PMH).Medical historycomprises HPI and PMH.

- Medications(Rx): what drugs the patient takes includingprescribed,over-the-counter, andhome remedies, as well as alternative andherbal medicines or remedies.Allergiesare also recorded.

- Past medical history (PMH/PMHx): concurrent medical problems, past hospitalizations and operations, injuries, pastinfectious diseasesorvaccinations, history of known allergies.

- Review of systems (ROS) orsystems inquiry: a set of additional questions to ask, which may be missed on HPI: a general enquiry (have you noticed anyweight loss, change in sleep quality, fevers, lumps and bumps? etc.), followed by questions on the body's main organ systems (heart,lungs,digestive tract,urinary tract, etc.).

- Social history (SH): birthplace, residences, marital history, social and economic status, habits (includingdiet, medications,tobacco, alcohol).

The physical examination is the examination of the patient for medical signs of disease that are objective and observable, in contrast to symptoms that are volunteered by the patient and are not necessarily objectively observable.[12]The healthcare provider uses sight, hearing, touch, and sometimes smell (e.g., in infection,uremia,diabetic ketoacidosis). Four actions are the basis of physical examination:inspection,palpation(feel),percussion(tap to determine resonance characteristics), andauscultation(listen), generally in that order, although auscultation occurs prior to percussion and palpation for abdominal assessments.[13]

The clinical examination involves the study of:[14]

- Abdomenandrectum

- Cardiovascular(heartandblood vessels)

- General appearance of the patient and specific indicators of disease (nutritional status, presence of jaundice, pallor orclubbing)

- Genitalia (and pregnancy if the patient is or could be pregnant)

- Head,eye,ear, nose, and throat (HEENT)[14]

- Musculoskeletal(including spine and extremities)

- Neurological(consciousness, awareness, brain, vision,cranial nerves, spinal cord andperipheral nerves)

- Psychiatric(orientation,mental state, mood, evidence of abnormal perception or thought).

- Respiratory(large airways andlungs)[14]

- Skin

- Vital signs including height, weight, body temperature,blood pressure,pulse, respiration rate, and hemoglobinoxygen saturation[14]

It is to likely focus on areas of interest highlighted in the medical history and may not include everything listed above.

The treatment plan may include ordering additionalmedical laboratorytests andmedical imagingstudies, starting therapy, referral to aspecialist, or watchful observation. A follow-up may be advised. Depending upon thehealth insuranceplan and themanaged caresystem, various forms of "utilization review", such as prior authorization of tests, may place barriers on accessing expensive services.[15]

The medical decision-making (MDM) process includes the analysis and synthesis of all the above data to come up with a list of possible diagnoses (the differential diagnoses), along with an idea of what needs to be done to obtain a definitive diagnosis that would explain the patient's problem.

On subsequent visits, the process may be repeated in an abbreviated manner to obtain any new history, symptoms, physical findings, lab or imaging results, or specialistconsultations.

Institutions

[edit]

Contemporary medicine is, in general, conducted withinhealth care systems. Legal,credentialing, and financing frameworks are established by individual governments, augmented on occasion by international organizations, such as churches. The characteristics of any given health care system have a significant impact on the way medical care is provided.

From ancient times, Christian emphasis on practical charity gave rise to the development of systematic nursing and hospitals, and theCatholic Churchtoday remains the largest non-government provider of medical services in the world.[16]Advanced industrial countries (with the exception of theUnited States)[17][18]and many developing countries provide medical services through a system ofuniversal health carethat aims to guarantee care for all through asingle-payer health caresystem or compulsory private or cooperative health insurance. This is intended to ensure that the entire population has access to medical care on the basis of need rather than ability to pay. Delivery may be via private medical practices, state-owned hospitals and clinics, or charities, most commonly a combination of all three.

Mosttribalsocieties provide no guarantee of healthcare for the population as a whole. In such societies, healthcare is available to those who can afford to pay for it, have self-insured it (either directly or as part of an employment contract), or may be covered by care financed directly by the government or tribe.

Transparency of information is another factor defining a delivery system. Access to information on conditions, treatments, quality, and pricing greatly affects the choice of patients/consumers and, therefore, the incentives of medical professionals. While the US healthcare system has come under fire for its lack of openness,[19]new legislation may encourage greater openness. There is a perceived tension between the need for transparency on the one hand and such issues as patient confidentiality and the possible exploitation of information for commercial gain on the other.

Thehealth professionalswho provide care in medicine comprise multipleprofessions, such asmedics,nurses,physiotherapists, andpsychologists. These professions will have their ownethical standards, professional education, and bodies. The medical profession has been conceptualized from asociological perspective.[20]

Delivery

[edit]Provision of medical care is classified into primary, secondary, and tertiary care categories.[21]

Primary caremedical services are provided byphysicians,physician assistants,nurse practitioners, or other health professionals who have first contact with a patient seeking medical treatment or care.[22]These occur in physician offices,clinics,nursing homes, schools, home visits, and other places close to patients. About 90% of medical visits can be treated by the primary care provider. These include treatment of acute and chronic illnesses,preventive careandhealth educationfor all ages and both sexes.

Secondary caremedical services are provided bymedical specialistsin their offices or clinics or at local community hospitals for a patient referred by a primary care provider who first diagnosed or treated the patient.[23]Referrals are made for those patients who required the expertise or procedures performed by specialists. These include bothambulatory careandinpatientservices,emergency departments,intensive care medicine, surgery services,physical therapy,labor and delivery,endoscopyunits, diagnostic laboratory and medical imaging services,hospicecenters, etc. Some primary care providers may also take care of hospitalized patients and deliver babies in a secondary care setting.

Tertiary caremedical services are provided by specialist hospitals or regional centers equipped with diagnostic and treatment facilities not generally available at local hospitals. These includetrauma centers,burntreatment centers, advancedneonatologyunit services,organ transplants, high-risk pregnancy,radiationoncology, etc.

Modern medical care also depends on information – still delivered in many health care settings on paper records, but increasingly nowadays byelectronic means.

In low-income countries, modern healthcare is often too expensive for the average person. International healthcare policy researchers have advocated that "user fees" be removed in these areas to ensure access, although even after removal, significant costs and barriers remain.[24]

Separation of prescribing and dispensingis a practice in medicine and pharmacy in which the physician who provides amedical prescriptionis independent from thepharmacistwho provides theprescription drug. In the Western world there are centuries of tradition for separating pharmacists from physicians. In Asian countries, it is traditional for physicians to also provide drugs.[25]

Branches

[edit]

Working together as aninterdisciplinary team, many highly trainedhealth professionalsbesides medical practitioners are involved in the delivery of modern health care. Examples include:nurses,emergency medical techniciansandparamedics, laboratory scientists,pharmacists,podiatrists,physiotherapists,respiratory therapists,speech therapists,occupational therapists, radiographers,dietitians, andbioengineers,medical physicists,surgeons,surgeon's assistant,surgical technologist.

The scope and sciences underpinning human medicine overlap many other fields. A patient admitted to the hospital is usually under the care of a specific team based on their main presenting problem, e.g., the cardiology team, who then may interact with other specialties, e.g., surgical, radiology, to help diagnose or treat the main problem or any subsequent complications/developments.

Physicians have many specializations and subspecializations into certain branches of medicine, which are listed below. There are variations from country to country regarding which specialties certain subspecialties are in.

The main branches of medicine are:

- Basic sciences of medicine; this is what every physician is educated in, and some return to inbiomedical research.

- Interdisciplinary fields, where different medical specialties are mixed to function in certain occasions.

- Medical specialties

Basic sciences

[edit]- Anatomyis the study of the physical structure oforganisms. In contrast tomacroscopicorgross anatomy,cytologyandhistologyare concerned with microscopic structures.

- Biochemistryis the study of the chemistry taking place in living organisms, especially the structure and function of their chemical components.

- Biomechanicsis the study of the structure and function of biological systems by means of the methods ofMechanics.

- Biophysicsis an interdisciplinary science that uses the methods ofphysicsandphysical chemistryto study biological systems.

- Biostatisticsis the application of statistics to biological fields in the broadest sense. A knowledge of biostatistics is essential in the planning, evaluation, and interpretation of medical research. It is also fundamental toepidemiologyand evidence-based medicine.

- Cytologyis the microscopic study of individualcells.

- Embryologyis the study of the early development of organisms.

- Endocrinologyis the study of hormones and their effect throughout the body of animals.

- Epidemiologyis the study of the demographics of disease processes, and includes, but is not limited to, the study of epidemics.

- Geneticsis the study of genes, and their role inbiological inheritance.

- Gynecologyis the study of female reproductive system.

- Histologyis the study of the structures ofbiological tissuesby lightmicroscopy,electron microscopyandimmunohistochemistry.

- Immunologyis the study of theimmune system, which includes the innate and adaptive immune system in humans, for example.

- Lifestyle medicineis the study of thechronic conditions, and how to prevent, treat and reverse them.

- Medical physicsis the study of the applications of physics principles in medicine.

- Microbiologyis the study ofmicroorganisms, includingprotozoa,bacteria,fungi, andviruses.

- Molecular biologyis the study of molecular underpinnings of the process ofreplication,transcriptionandtranslationof the genetic material.

- Neuroscienceincludes those disciplines of science that are related to the study of thenervous system. A main focus of neuroscience is thebiologyand physiology of the human brain andspinal cord. Some related clinical specialties includeneurology,neurosurgeryandpsychiatry.

- Nutrition science(theoretical focus) anddietetics(practical focus) is the study of the relationship of food and drink to health and disease, especially in determining an optimal diet. Medical nutrition therapy is done by dietitians and is prescribed fordiabetes,cardiovascular diseases, weight and eatingdisorders, allergies,malnutrition, andneoplasticdiseases.

- Pathology as a scienceis the study of disease – the causes, course, progression and resolution thereof.

- Pharmacologyis the study of drugs and their actions.

- Photobiologyis the study of the interactions betweennon-ionizing radiationand living organisms.

- Physiologyis the study of the normal functioning of the body and the underlying regulatory mechanisms.

- Radiobiologyis the study of the interactions betweenionizing radiationand living organisms.

- Toxicologyis the study of hazardous effects of drugs andpoisons.

Specialties

[edit]|

|

The examples and perspective in this section

deal primarily with UK and do not represent aworldwide viewof the subject.

(February 2023)

|

In the broadest meaning of "medicine", there are many different specialties. In the UK, most specialities have their own body or college, which has its own entrance examination. These are collectively known as the Royal Colleges, although not all currently use the term "Royal". The development of a speciality is often driven by new technology (such as the development of effective anaesthetics) or ways of working (such as emergency departments); the new specialty leads to the formation of a unifying body of doctors and the prestige of administering their own examination.

Within medical circles, specialities usually fit into one of two broad categories: "Medicine" and "Surgery". "Medicine" refers to the practice of non-operative medicine, and most of its subspecialties require preliminary training in Internal Medicine. In the UK, this was traditionally evidenced by passing the examination for the Membership of theRoyal College of Physicians(MRCP) or the equivalent college in Scotland or Ireland. "Surgery" refers to the practice of operative medicine, and most subspecialties in this area require preliminary training in General Surgery, which in the UK leads to membership of theRoyal College of Surgeons of England(MRCS). At present, some specialties of medicine do not fit easily into either of these categories, such as radiology, pathology, or anesthesia. Most of these have branched from one or other of the two camps above; for example anaesthesia developed first as afacultyof the Royal College of Surgeons (for which MRCS/FRCS would have been required) before becoming theRoyal College of Anaesthetistsand membership of the college is attained by sitting for the examination of the Fellowship of the Royal College of Anesthetists (FRCA).

Surgical specialty

[edit]

Surgeryis an ancient medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a patient to investigate or treat apathologicalcondition such as disease orinjury, to help improve bodily function or appearance or to repair unwanted ruptured areas (for example,a perforated ear drum). Surgeons must also manage pre-operative, post-operative, and potential surgical candidates on the hospital wards. In some centers,anesthesiologyis part of the division of surgery (for historical and logistical reasons), although it is not a surgical discipline. Other medical specialties may employ surgical procedures, such asophthalmologyanddermatology, but are not considered surgical sub-specialties per se.

Surgical training in the U.S. requires a minimum of five years of residency after medical school. Sub-specialties of surgery often require seven or more years. In addition, fellowships can last an additional one to three years. Because post-residency fellowships can be competitive, many trainees devote two additional years to research. Thus in some cases surgical training will not finish until more than a decade after medical school. Furthermore, surgical training can be very difficult and time-consuming.

Surgical subspecialties include those a physician may specialize in after undergoing general surgery residency training as well as several surgical fields with separate residency training. Surgical subspecialties that one may pursue following general surgery residency training:[26]

- Bariatric surgery

- Cardiovascular surgery– may also be pursued through a separate cardiovascular surgery residency track

- Colorectal surgery

- Endocrine surgery

- General surgery

- Hand surgery

- Hepatico-Pancreatico-Biliary Surgery

- Minimally invasive surgery

- Pediatric surgery

- Plastic surgery– may also be pursued through a separate plastic surgery residency track

- Surgical critical care

- Surgical oncology

- Transplant surgery

- Trauma surgery

- Vascular surgery– may also be pursued through a separate vascular surgery residency track

Other surgical specialties within medicine with their own individual residency training:

- Dermatology

- Neurosurgery

- Ophthalmology

- Oral and maxillofacial surgery

- Orthopedic surgery

- Otorhinolaryngology

- Podiatric surgery– do not undergo medical school training, but rather separate training in podiatry school

- Urology

Internal medicine specialty

[edit]Internal medicineis themedical specialtydealing with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of adult diseases.[27]According to some sources, an emphasis on internal structures is implied.[28]In North America, specialists in internal medicine are commonly called "internists". Elsewhere, especially inCommonwealthnations, such specialists are often calledphysicians.[29]These terms,internistorphysician(in the narrow sense, common outside North America), generally exclude practitioners of gynecology and obstetrics, pathology, psychiatry, and especially surgery and its subspecialities.

Because their patients are often seriously ill or require complex investigations, internists do much of their work in hospitals. Formerly, many internists were not subspecialized; suchgeneral physicianswould see any complex nonsurgical problem; this style of practice has become much less common. In modern urban practice, most internists are subspecialists: that is, they generally limit their medical practice to problems of one organ system or to one particular area of medical knowledge. For example,gastroenterologistsandnephrologistsspecialize respectively in diseases of the gut and the kidneys.[30]

In the Commonwealth of Nations and some other countries, specialistpediatriciansandgeriatriciansare also described asspecialist physicians(or internists) who have subspecialized by age of patient rather than by organ system. Elsewhere, especially in North America, general pediatrics is often a form ofprimary care.

There are many subspecialities (or subdisciplines) ofinternal medicine:

-

- Angiology/Vascular Medicine

- Bariatrics

- Cardiology

- Critical care medicine

- Endocrinology

- Gastroenterology

- Geriatrics

- Hematology

- Hepatology

- Infectious disease

- Nephrology

- Neurology

- Oncology

- Pediatrics

- Pulmonology/Pneumology/Respirology/chest medicine

- Rheumatology

- Sports Medicine

Training in internal medicine (as opposed to surgical training), varies considerably across the world: see the articles onmedical educationfor more details. In North America, it requires at least three years of residency training after medical school, which can then be followed by a one- to three-year fellowship in the subspecialties listed above. In general, resident work hours in medicine are less than those in surgery, averaging about 60 hours per week in the US. This difference does not apply in the UK where all doctors are now required by law to work less than 48 hours per week on average.

Diagnostic specialties

[edit]- Clinical laboratorysciencesare the clinical diagnostic services that apply laboratory techniques to diagnosis and management of patients. In the United States, these services are supervised by a pathologist. The personnel that work in thesemedical laboratorydepartments are technically trained staff who do not hold medical degrees, but who usually hold an undergraduatemedical technologydegree, who actually perform thetests,assays, and procedures needed for providing the specific services. Subspecialties includetransfusion medicine,cellular pathology,clinical chemistry,hematology,clinical microbiologyandclinical immunology.

- Clinical neurophysiologyis concerned with testing the physiology or function of the central and peripheral aspects of the nervous system. These kinds of tests can be divided into recordings of: (1) spontaneous or continuously running electrical activity, or (2) stimulus evoked responses. Subspecialties includeelectroencephalography,electromyography,evoked potential,nerve conduction studyandpolysomnography. Sometimes these tests are performed by techs without a medical degree, but the interpretation of these tests is done by a medical professional.

- Diagnosticradiologyis concerned with imaging of the body, e.g. byx-rays, x-raycomputed tomography,ultrasonography, andnuclear magnetic resonancetomography. Interventional radiologists can access areas in the body under imaging for an intervention or diagnostic sampling.

- Nuclear medicineis concerned with studying human organ systems by administering radiolabelled substances (radiopharmaceuticals) to the body, which can then be imaged outside the body by agamma cameraor a PET scanner. Each radiopharmaceutical consists of two parts: a tracer that is specific for the function under study (e.g., neurotransmitter pathway, metabolic pathway, blood flow, or other), and a radionuclide (usually either a gamma-emitter or a positron emitter). There is a degree of overlap between nuclear medicine and radiology, as evidenced by the emergence of combined devices such as the PET/CT scanner.

- Pathology as a medical specialtyis the branch of medicine that deals with the study of diseases and the morphologic, physiologic changes produced by them. As a diagnostic specialty, pathology can be considered the basis of modern scientific medical knowledge and plays a large role inevidence-based medicine. Many modern molecular tests such asflow cytometry,polymerase chain reaction(PCR),immunohistochemistry,cytogenetics, gene rearrangements studies andfluorescent in situ hybridization(FISH) fall within the territory of pathology.

Other major specialties

[edit]The following are some major medical specialties that do not directly fit into any of the above-mentioned groups:

- Anesthesiology(also known asanaesthetics): concerned with the perioperative management of the surgical patient. The anesthesiologist's role during surgery is to prevent derangement in the vital organs' (i.e. brain, heart, kidneys) functions and postoperative pain. Outside of the operating room, the anesthesiology physician also serves the same function in the labor and delivery ward, and some are specialized in critical medicine.

- Emergency medicineis concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of acute or life-threatening conditions, includingtrauma, surgical, medical, pediatric, and psychiatric emergencies.

- Family medicine,family practice,general practiceorprimary careis, in many countries, the first port-of-call for patients with non-emergency medical problems. Family physicians often provide services across a broad range of settings including office based practices, emergency department coverage, inpatient care, and nursing home care.

- Medical geneticsis concerned with the diagnosis and management of hereditary disorders.

- Neurologyis concerned with diseases of the nervous system. In the UK, neurology is a subspecialty of general medicine.

- Obstetricsandgynecology(often abbreviated asOB/GYN(American English) orObs & Gynae(British English)) are concerned respectively with childbirth and the female reproductive and associated organs.Reproductive medicineandfertility medicineare generally practiced by gynecological specialists.

- Pediatrics(AE) orpaediatrics(BE) is devoted to the care of infants, children, and adolescents. Like internal medicine, there are many pediatric subspecialties for specific age ranges, organ systems, disease classes, and sites of care delivery.

- Pharmaceutical medicineis the medical scientific discipline concerned with the discovery, development, evaluation, registration, monitoring and medical aspects of marketing of medicines for the benefit of patients and public health.

- Physical medicine and rehabilitation(orphysiatry) is concerned with functional improvement after injury, illness, orcongenital disorders.

- Podiatric medicineis the study of, diagnosis, and medical and surgical treatment of disorders of the foot, ankle, lower limb, hip and lower back.

- Preventive medicineis the branch of medicine concerned with preventing disease.

- Community healthorpublic healthis an aspect of health services concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based onpopulation healthanalysis.

- Psychiatryis the branch of medicine concerned with thebio-psycho-socialstudy of theetiology, diagnosis, treatment and prevention ofcognitive,perceptual,emotionalandbehavioraldisorders. Related fields includepsychotherapyandclinical psychology.

Interdisciplinary fields

[edit]Some interdisciplinary sub-specialties of medicine include:

- Addiction medicinedeals with the treatment of addiction.

- Aerospace medicinedeals with medical problems related to flying andspace travel.

- Biomedical Engineeringis a field dealing with the application ofengineeringprinciples to medical practice.

- Clinical pharmacologyis concerned with how systems oftherapeuticsinteract with patients.

- Conservation medicinestudies the relationship between human and non-human animal health, and environmental conditions. Also known as ecological medicine,environmental medicine, ormedical geology.

- Disaster medicinedeals with medical aspects of emergency preparedness, disaster mitigation and management.

- Diving medicine(orhyperbaric medicine) is the prevention and treatment of diving-related problems.

- Evolutionary medicineis a perspective on medicine derived through applyingevolutionarytheory.

- Forensic medicinedeals with medical questions inlegalcontext, such as determination of the time and cause of death, type of weapon used to inflict trauma, reconstruction of the facial features using remains of deceased (skull) thus aiding identification.

- Gender-based medicinestudies the biological and physiological differences between the human sexes and how that affects differences in disease.

- Health informaticsis a relatively recent field that deal with the application of computers andinformation technologyto medicine.

- Hospice and Palliative Medicineis a relatively modern branch of clinical medicine that deals with pain and symptom relief and emotional support in patients withterminal illnessesincluding cancer andheart failure.

- Hospital medicineis the general medical care of hospitalized patients. Physicians whose primary professional focus is hospital medicine are calledhospitalistsin the United States andCanada. The term Most Responsible Physician (MRP) or attending physician is also used interchangeably to describe this role.

- Laser medicineinvolves the use of lasers in the diagnostics or treatment of various conditions.

- Many otherhealth sciencefields, e.g.dietetics

- Medical ethicsdeals withethicalandmoralprinciples that apply values and judgments to the practice of medicine.

- Medical humanitiesincludes thehumanities(literature,philosophy,ethics, history and religion),social science(anthropology,cultural studies,psychology,sociology), and the arts (literature, theater, film, andvisual arts) and their application tomedical educationand practice.

- Nosokineticsis the science/subject of measuring and modelling the process of care in health and social care systems.

- Nosologyis the classification of diseases for various purposes.

- Occupational medicineis the provision of health advice to organizations and individuals to ensure that the highest standards of health and safety at work can be achieved and maintained.

- Pain management(also calledpain medicine, oralgiatry) is the medical discipline concerned with the relief of pain.

- Pharmacogenomicsis a form ofindividualized medicine.

- Podiatric medicineis the study of, diagnosis, and medical treatment of disorders of the foot, ankle, lower limb, hip and lower back.

- Sexual medicineis concerned with diagnosing, assessing and treating all disorders related to sexuality.

- Sports medicinedeals with the treatment and prevention and rehabilitation of sports/exercise injuries such asmuscle spasms,muscle tears, injuries to ligaments (ligament tears or ruptures) and their repair inathletes,amateurandprofessional.

- Therapeuticsis the field, more commonly referenced in earlier periods of history, of the various remedies that can be used to treat disease and promote health.[31]

- Travel medicineoremporiatricsdeals with health problems of international travelers or travelers across highly different environments.

- Tropical medicinedeals with the prevention and treatment of tropical diseases. It is studied separately in temperate climates where those diseases are quite unfamiliar to medical practitioners and their local clinical needs.

- Urgent carefocuses on delivery of unscheduled, walk-in care outside of the hospital emergency department for injuries and illnesses that are not severe enough to require care in an emergency department. In some jurisdictions this function is combined with the emergency department.

- Veterinary medicine;veterinariansapply similar techniques as physicians to the care of non-human animals.

- Wilderness medicineentails the practice of medicine in the wild, where conventional medical facilities may not be available.

Education and legal controls

[edit]

Medical education and training varies around the world. It typically involves entry level education at a universitymedical school, followed by a period of supervised practice orinternship, orresidency. This can be followed by postgraduate vocational training. A variety of teaching methods have been employed in medical education, still itself a focus of active research. In Canada and the United States of America, a Doctor of Medicine degree, often abbreviated M.D., or aDoctor of Osteopathic Medicinedegree, often abbreviated as D.O. and unique to the United States, must be completed in and delivered from a recognized university.

Since knowledge, techniques, and medical technology continue to evolve at a rapid rate, many regulatory authorities requirecontinuing medical education. Medical practitioners upgrade their knowledge in various ways, includingmedical journals, seminars, conferences, and online programs. A database of objectives covering medical knowledge, as suggested by national societies across the United States, can be searched athttp://data.medobjectives.marian.edu/Archived4 October 2018 at theWayback Machine.[32]

In most countries, it is a legal requirement for a medical doctor to be licensed or registered. In general, this entails a medical degree from a university and accreditation by a medical board or an equivalent national organization, which may ask the applicant to pass exams. This restricts the considerable legal authority of the medical profession to physicians that are trained and qualified by national standards. It is also intended as an assurance to patients and as a safeguard againstcharlatansthat practice inadequate medicine for personal gain. While the laws generally require medical doctors to be trained in "evidence based", Western, orHippocraticMedicine, they are not intended to discourage different paradigms of health.

In the European Union, the profession of doctor of medicine is regulated. A profession is said to be regulated when access and exercise is subject to the possession of a specific professional qualification. The regulated professions database contains a list of regulated professions for doctor of medicine in the EU member states, EEA countries and Switzerland. This list is covered by theDirective 2005/36/EC.

Doctors who are negligent or intentionally harmful in their care of patients can face charges ofmedical malpracticeand be subject to civil, criminal, or professional sanctions.

Medical ethics

[edit]

Medical ethics is a system of moral principles that apply values and judgments to the practice of medicine. As a scholarly discipline, medical ethics encompasses its practical application in clinical settings as well as work on its history, philosophy, theology, and sociology. Six of the values that commonly apply to medical ethics discussions are:

- autonomy– the patient has the right to refuse or choose their treatment. (Latin:Voluntas aegroti suprema lex.)

- beneficence– a practitioner should act in the best interest of the patient. (Latin:Salus aegroti suprema lex.)

- justice– concerns the distribution of scarce health resources, and the decision of who gets what treatment (fairness and equality).

- non-maleficence– "first, do no harm" (Latin:primum non-nocere).

- respect for persons– the patient (and the person treating the patient) have the right to be treated with dignity.

- truthfulnessandhonesty– the concept ofinformed consenthas increased in importance since the historical events of theDoctors' Trialof the Nuremberg trials,Tuskegee syphilis experiment, and others.

Values such as these do not give answers as to how to handle a particular situation, but provide a useful framework for understanding conflicts. When moral values are in conflict, the result may be an ethicaldilemmaor crisis. Sometimes, no good solution to a dilemma in medical ethics exists, and occasionally, the values of the medical community (i.e., the hospital and its staff) conflict with the values of the individual patient, family, or larger non-medical community. Conflicts can also arise between health care providers, or among family members. For example, some argue that the principles of autonomy and beneficence clash when patients refuseblood transfusions, considering them life-saving; and truth-telling was not emphasized to a large extent before the HIV era.

History

[edit]

Ancient world

[edit]Prehistoric medicineincorporated plants (herbalism), animal parts, and minerals. In many cases these materials were used ritually as magical substances by priests,shamans, ormedicine men. Well-known spiritual systems includeanimism(the notion of inanimate objects having spirits),spiritualism(an appeal to gods or communion with ancestor spirits);shamanism(the vesting of an individual with mystic powers); anddivination(magically obtaining the truth). The field ofmedical anthropologyexamines the ways in which culture and society are organized around or impacted by issues of health, health care and related issues.

The earliest known medical texts in the world were found in the ancientSyriancity ofEblaand date back to 2500 BCE.[33][34][35]Other early records on medicine have been discovered fromancient Egyptian medicine,Babylonian Medicine,Ayurvedicmedicine (in theIndian subcontinent),classical Chinese medicine(Alternative medicine) predecessor to the moderntraditional Chinese medicine), andancient Greek medicineandRoman medicine.

In Egypt,Imhotep(3rd millennium BCE) is the first physician in history known by name. The oldestEgyptian medical textis theKahun Gynaecological Papyrusfrom around 2000 BCE, which describes gynaecological diseases. TheEdwin Smith Papyrusdating back to 1600 BCE is an early work on surgery, while theEbers Papyrusdating back to 1500 BCE is akin to a textbook on medicine.[36]

In China, archaeological evidence of medicine in Chinese dates back to theBronze AgeShang dynasty, based on seeds for herbalism and tools presumed to have been used for surgery.[37]TheHuangdi Neijing, the progenitor of Chinese medicine, is a medical text written beginning in the 2nd century BCE and compiled in the 3rd century.[38]

In India, the surgeonSushrutadescribed numerous surgical operations, including the earliest forms ofplastic surgery.[39][unreliable source?][citation needed]Earliest records of dedicated hospitals come from Mihintale inSri Lankawhere evidence of dedicated medicinal treatment facilities for patients are found.[40][41]

In Greece, the ancient Greek physicianHippocrates, the "father of modern medicine",[42][43]laid the foundation for a rational approach to medicine. Hippocrates introduced theHippocratic Oathfor physicians, which is still relevant and in use today, and was the first to categorize illnesses asacute,chronic,endemicand epidemic, and use terms such as, "exacerbation,relapse, resolution, crisis,paroxysm, peak, andconvalescence".[44][45]The Greek physicianGalenwas also one of the greatest surgeons of the ancient world and performed many audacious operations, including brain and eye surgeries. After the fall of theWestern Roman Empireand the onset of theEarly Middle Ages, the Greek tradition of medicine went into decline in Western Europe, although it continued uninterrupted in theEastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire.

Most of our knowledge of ancientHebrew medicineduring the1st millennium BCcomes from theTorah, i.e. the Five Books ofMoses, which contain various health related laws and rituals. The Hebrew contribution to the development of modern medicine started in theByzantine Era, with the physicianAsaph the Jew.[46]

Middle Ages

[edit]

The concept of hospital as institution to offer medical care and possibility of a cure for the patients due to the ideals of Christian charity, rather than just merely a place to die, appeared in theByzantine Empire.[47]

Although the concept ofuroscopywas known to Galen, he did not see the importance of using it to localize the disease. It was under the Byzantines with physicians such ofTheophilus Protospathariusthat they realized the potential in uroscopy to determine disease in a time when no microscope or stethoscope existed. That practice eventually spread to the rest of Europe.[48]

After 750 CE, the Muslim world had the works of Hippocrates, Galen and Sushruta translated intoArabic, andIslamic physiciansengaged in some significant medical research. Notable Islamic medical pioneers include the Persianpolymath,Avicenna, who, along with Imhotep and Hippocrates, has also been called the "father of medicine".[49]He wroteThe Canon of Medicinewhich became a standard medical text at many medieval Europeanuniversities,[50]considered one of the most famous books in the history of medicine.[51]Others includeAbulcasis,[52]Avenzoar,[53]Ibn al-Nafis,[54]andAverroes.[55]PersianphysicianRhazes[56]was one of the first to question the Greek theory ofhumorism, which nevertheless remained influential in both medieval Western and medieval Islamic medicine.[57]Some volumes of Rhazes's workAl-Mansuri, namely "On Surgery" and "A General Book on Therapy", became part of the medical curriculum in European universities.[58]Additionally, he has been described as a doctor's doctor,[59]the father of pediatrics,[56][60]and a pioneer of ophthalmology. For example, he was the first to recognize the reaction of the eye's pupil to light.[60]The PersianBimaristanhospitals were an early example ofpublic hospitals.[61][62]

In Europe,Charlemagnedecreed that a hospital should be attached to each cathedral and monastery and the historianGeoffrey Blaineylikened theactivities of the Catholic Church in health careduring the Middle Ages to an early version of a welfare state: "It conducted hospitals for the old and orphanages for the young; hospices for the sick of all ages; places for the lepers; and hostels or inns where pilgrims could buy a cheap bed and meal". It supplied food to the population during famine and distributed food to the poor. This welfare system the church funded through collecting taxes on a large scale and possessing large farmlands and estates. TheBenedictineorder was noted for setting up hospitals and infirmaries in their monasteries, growing medical herbs and becoming the chief medical care givers of their districts, as at the greatAbbey of Cluny. The Church also established a network ofcathedral schoolsand universities where medicine was studied. TheSchola Medica Salernitanain Salerno, looking to the learning ofGreekandArabphysicians, grew to be the finest medical school in Medieval Europe.[63]

However, the fourteenth and fifteenth centuryBlack Deathdevastated both the Middle East and Europe, and it has even been argued that Western Europe was generally more effective in recovering from the pandemic than the Middle East.[64]In the early modern period, important early figures in medicine and anatomy emerged in Europe, includingGabriele FalloppioandWilliam Harvey.

The major shift in medical thinking was the gradual rejection, especially during theBlack Deathin the 14th and 15th centuries, of what may be called the "traditional authority" approach to science and medicine. This was the notion that because some prominent person in the past said something must be so, then that was the way it was, and anything one observed to the contrary was an anomaly (which was paralleled by a similar shift in European society in general – seeCopernicus's rejection ofPtolemy's theories on astronomy). Physicians likeVesaliusimproved upon or disproved some of the theories from the past. The main tomes used both by medicine students and expert physicians wereMateria MedicaandPharmacopoeia.

Andreas Vesaliuswas the author ofDe humani corporis fabrica, an important book onhuman anatomy.[65]Bacteria and microorganisms were first observed with a microscope byAntonie van Leeuwenhoekin 1676, initiating the scientific fieldmicrobiology.[66]Independently from Ibn al-Nafis,Michael Servetusrediscovered thepulmonary circulation, but this discovery did not reach the public because it was written down for the first time in the "Manuscript of Paris"[67]in 1546, and later published in the theological work for which he paid with his life in 1553. Later this was described byRenaldus ColumbusandAndrea Cesalpino.Herman Boerhaaveis sometimes referred to as a "father of physiology" due to his exemplary teaching in Leiden and textbook 'Institutiones medicae' (1708).Pierre Fauchardhas been called "the father of moderndentistry".[68]

Modern

[edit]

Veterinary medicine was, for the first time, truly separated from human medicine in 1761, when the French veterinarianClaude Bourgelatfounded the world's first veterinary school in Lyon, France. Before this, medical doctors treated both humans and other animals.

Modern scientificbiomedical research(where results are testable andreproducible) began to replace early Western traditions based on herbalism, the Greek "four humours" and other such pre-modern notions. The modern era really began withEdward Jenner's discovery of thesmallpox vaccineat the end of the 18th century (inspired by the method ofvariolationoriginated in ancient China),[69]Robert Koch's discoveries around 1880 of the transmission of disease by bacteria, and then the discovery ofantibioticsaround 1900.

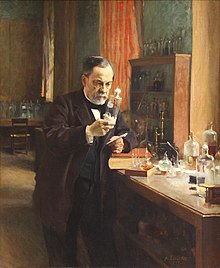

The post-18th centurymodernityperiod brought more groundbreaking researchers from Europe. FromGermanyand Austria, doctorsRudolf Virchow,Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen,Karl LandsteinerandOtto Loewimade notable contributions. In theUnited Kingdom,Alexander Fleming,Joseph Lister,Francis CrickandFlorence Nightingaleare considered important.SpanishdoctorSantiago Ramón y Cajalis considered the father of modernneuroscience.

From New Zealand and Australia cameMaurice Wilkins,Howard Florey, andFrank Macfarlane Burnet.

Others that did significant work includeWilliam Williams Keen,William Coley,James D. Watson(United States);Salvador Luria(Italy);Alexandre Yersin(Switzerland);Kitasato Shibasaburō(Japan);Jean-Martin Charcot,Claude Bernard,Paul Broca(France);Adolfo Lutz(Brazil);Nikolai Korotkov(Russia);Sir William Osler(Canada); andHarvey Cushing(United States).

As science and technology developed, medicine became more reliant uponmedications. Throughout history and in Europe right until the late 18th century, not only plant products were used as medicine, but also animal (including human) body parts and fluids.[70]Pharmacologydeveloped in part from herbalism and some drugs are still derived from plants (atropine,ephedrine,warfarin,aspirin,digoxin,vincaalkaloids,[71]taxol,hyoscine, etc.).[72]Vaccineswere discovered by Edward Jenner andLouis Pasteur.

The first antibiotic wasarsphenamine(Salvarsan) discovered byPaul Ehrlichin 1908 after he observed that bacteria took up toxic dyes that human cells did not. The first major class of antibiotics was thesulfa drugs, derived by German chemists originally fromazo dyes.

Pharmacology has become increasingly sophisticated; modernbiotechnologyallows drugs targeted towards specific physiological processes to be developed, sometimes designed for compatibility with the body to reduceside-effects.Genomicsand knowledge ofhuman geneticsandhuman evolutionis having increasingly significant influence on medicine, as the causativegenesof most monogenicgenetic disordershave now been identified, and the development of techniques inmolecular biology,evolution, andgeneticsare influencing medical technology, practice and decision-making.

Evidence-based medicine is a contemporary movement to establish the most effectivealgorithmsof practice (ways of doing things) through the use ofsystematic reviewsandmeta-analysis. The movement is facilitated by modern globalinformation science, which allows as much of the available evidence as possible to be collected and analyzed according to standard protocols that are then disseminated to healthcare providers. TheCochrane Collaborationleads this movement. A 2001 review of 160 Cochrane systematic reviews revealed that, according to two readers, 21.3% of the reviews concluded insufficient evidence, 20% concluded evidence of no effect, and 22.5% concluded positive effect.[73]

Quality, efficiency, and access

[edit]Evidence-based medicine, prevention ofmedical error(and other "iatrogenesis"), and avoidance ofunnecessary health careare a priority in modern medical systems. These topics generate significant political and public policy attention, particularly in the United States where healthcare is regarded as excessively costly butpopulation healthmetrics lag similar nations.[74]

Globally, many developing countries lack access to care andaccess to medicines.[75]As of 2015[update], most wealthy developed countries provide health care to all citizens, with a few exceptions such as the United States where lack of health insurance coverage may limit access.[76]

See also

[edit]- Alternative medicine– Form of non-scientific healing

- List of causes of death by rate

- List of disorders

- List of important publications in medicine

- Lists of diseases

- Medical aid– Type of insurance

- Medical billing– Part of the US health system's reimbursement process

- Medical classification– Use of schemes of standardized codes

- Medical encyclopedia– Written compendium about diseases

- Medical equipment– Device to be used for medical purposes

- Medical ethics– System of moral principles of the practice of medicine

- Medical literature– Scientific literature of medicine

- Medical malpractice– Legal cause of action

- Medical psychology– Application of psychological principles to the practice of medicine

- Medical sociology– Branch of sociology

- Philosophy of healthcare

- Quackery– Promotion of fraudulent or ignorant medical practices

- Traditional medicine– Formalized folk medicine

References

[edit]- ^Firth J (2020). "Science in medicine: when, how, and what".Oxford textbook of medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press.ISBN978-0-19-874669-0.

- ^Saunders J (June 2000)."The practice of clinical medicine as an art and as a science".Med Humanit.26(1): 18–22.doi:10.1136/mh.26.1.18.ISSN1468-215X.PMC1071282.PMID12484313.S2CID73306806.

- ^"Dictionary, medicine".Archivedfrom the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved2 December2013.

- ^"Medicine, n.1".OED Online. Oxford University Press. September 2014.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved8 November2014.

- ^"Medicine".Oxford Dictionaries Online. Oxford University Press.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved8 November2014.

- ^Etymology:Latin:medicina, fromars medicina"the medical art", frommedicus"physician". (Etym.OnlineArchived11 October 2007 at theWayback Machine) Cf.mederi"to heal", etym. "know the best course for", fromPIEbase *med- "to measure, limit. Cf.Greekmedos"counsel, plan",Avestanvi-mad"physician"

- ^"Medicine"Archived11 October 2007 at theWayback MachineOnline Etymology Dictionary

- ^"Traditional medicine: growing needs and potential".WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. No. 2.World Health Organization. 2002.hdl:10665/67294.

- ^El Dib RP, Atallah AN, Andriolo RB (August 2007). "Mapping the Cochrane evidence for decision making in health care".Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice.13(4): 689–692.doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00886.x.PMID17683315.

- ^abCoulehan JL, Block MR (2005).The Medical Interview: Mastering Skills for Clinical Practice(5th ed.). F. A. Davis.ISBN978-0-8036-1246-4.OCLC232304023.

- ^Addison K, Braden JH, Cupp JE, Emmert D, Hall LA, Hall T, et al. (September 2005)."Update: guidelines for defining the legal health record for-disclosure purposes".Journal of AHIMA.76(8): 64A–64G.PMID16245584. Archived fromthe originalon 9 March 2008.

- ^Nordqvist C (26 August 2009)."What Are Symptoms? What Are Signs?".Medical News Today. Archived fromthe originalon 1 July 2014.

- ^"Assessing patients effectively: Here's how to do the basic four techniques".Nursing2014.8(2): 6. 2006.doi:10.1097/00152193-200611002-00005.

- ^abcd"Clinical examination".The Free Dictionary.Archivedfrom the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved18 January2021.

- ^Grembowski DE,Diehr P, Novak LC, Roussel AE, Martin DP, Patrick DL, et al. (August 2000)."Measuring the "managedness" and covered benefits of health plans".Health Services Research.35(3): 707–734.PMC1089144.PMID10966092.

- ^Blainey G (2011).A Short History of Christianity. Penguin Viking.OCLC793902685.[page needed]

- ^"Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations". Institute of Medicine at the National Academies of Science. 14 January 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 19 October 2009.

- ^Battista JR, McCabe J (4 June 1999)."The Case For Single Payer, Universal Health Care for the United States". Cthealth.server101.com. Archived fromthe originalon 23 April 2018. Retrieved4 May2009.

- ^Sipkoff M (January 2004)."Transparency called key to uniting cost control, quality improvement".Managed Care.13(1): 38–42.PMID14763279.Archivedfrom the original on 17 February 2004. Retrieved16 April2006.

- ^Calnan M (2015). Collyer F (ed.)."Eliot Freidson: Sociological Narratives of Professionalism and Modern Medicine".The Palgrave Handbook of Social Theory in Health, Illness and Medicine. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 287–305.doi:10.1057/9781137355621_19.ISBN978-1-349-47022-8.Archivedfrom the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved6 November2021.

- ^"Primary, Secondary and Tertiary HealthCare – Arthapedia".www.arthapedia.in.Archivedfrom the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved19 January2021.

- ^"Types of health care providers: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia".medlineplus.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved19 January2021.

- ^"Secondary Health Care".International Medical Corps.Archivedfrom the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved19 January2021.

- ^Laokri S, Weil O, Drabo KM, Dembelé SM, Kafando B, Dujardin B (April 2013)."Removal of user fees no guarantee of universal health coverage: observations from Burkina Faso".Bulletin of the World Health Organization.91(4): 277–282.doi:10.2471/BLT.12.110015.PMC3629451.PMID23599551.

- ^Chou YJ, Yip WC, Lee CH, Huang N, Sun YP, Chang HJ (September 2003)."Impact of separating drug prescribing and dispensing on provider behaviour: Taiwan's experience".Health Policy and Planning.18(3): 316–329.doi:10.1093/heapol/czg038.PMID12917273.

- ^"What are the surgical specialties?".American College of Surgeons.Archivedfrom the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved18 January2021.

- ^Culyer AJ (31 July 2014).The Dictionary of Health Economics, Third Edition. Chelthenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 335.ISBN978-1-78100-199-8.Archivedfrom the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved18 January2021.

- ^"internal medicine"atDorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^Fowler HW (1994).A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (Wordsworth Collection) (Wordsworth Collection). NTC/Contemporary Publishing Company.ISBN978-1-85326-318-7.

- ^"The Royal Australasian College of Physicians: What are Physicians?".Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Archived fromthe originalon 6 March 2008. Retrieved5 February2008.

- ^"therapeutics (medicine)".Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Archived fromthe originalon 18 December 2007. Retrieved21 April2012.

- ^Brooks S, Biala N, Arbor S (March 2018)."A searchable database of medical education objectives – creating a comparable gold standard".BMC Medical Education.18(1): 31.doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1136-z.PMC5833091.PMID29499684.

- ^Radner K, Robson E (22 September 2011).The Oxford Handbook of Cuneiform Culture. OUP Oxford.ISBN978-0-19-955730-1.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved26 December2023.

- ^Vogel WH, Berke A (2009).Brief History of Vision and Ocular Medicine. Kugler Publications.ISBN978-90-6299-220-1.Archivedfrom the original on 27 February 2024. Retrieved26 December2023.

- ^Page(5)https://www.asor.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Five_Articles_about_Drugs_Medicine__Alcohol_From_ANEToday_E-book.pdfArchived20 January 2024 at theWayback Machine

- ^Ackerknecht E (1982).A Short History of Medicine. JHU Press. p.22.ISBN978-0-8018-2726-6.

- ^Hong F (2004)."History of Medicine in China"(PDF).McGill Journal of Medicine.8(1): 7984. Archived fromthe original(PDF)on 1 December 2013.

- ^Unschuld P (2003).Huang Di Nei Jing: Nature, Knowledge, Imagery in an Ancient Chinese Medical Text. University of California Press. p. ix.ISBN978-0-520-92849-7.Archivedfrom the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved14 November2015.

- ^Rana RE, Arora BS (2002). "History of plastic surgery in India".Journal of Postgraduate Medicine.48(1): 76–78.PMID12082339.

- ^Aluvihare A (November 1993). "Rohal Kramaya Lovata Dhayadha Kale Sri Lankikayo".Vidhusara Science Magazine: 5.

- ^Rannan-Eliya RP, De Mel N (9 February 1997)."Resource mobilization in Sri Lanka's health sector"(PDF).Harvard School of Public Health & Health Policy Programme, Institute of Policy Studies. p. 19.Archived(PDF)from the original on 29 October 2001. Retrieved16 July2009.

- ^Grammaticos PC, Diamantis A (2008). "Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and his teacher Democritus".Hellenic Journal of Nuclear Medicine.11(1): 2–4.PMID18392218.

- ^The father of modern medicine: the first research of the physical factor of tetanusArchived18 November 2011 at theWayback Machine, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

- ^Garrison FH (1966).History of Medicine.Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. p. 97.

- ^Martí-Ibáñez F (1961).A Prelude to Medical History.New York: MD Publications, Inc. p. 90. Library of Congress ID: 61-11617.

- ^Vaisrub S, A Denman M, Naparstek Y, Gilon D (2008)."Medicine".Encyclopaedia Judaica. The Gale Group.Archivedfrom the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved27 August2014.

- ^Lindberg D (1992).The Beginnings of Western Science. University of Chicago Press. p.349.ISBN978-0-226-48231-6.

- ^Prioreschi P (2004).A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine. Horatius Press. p. 146.

- ^Becka J (January 1980). "[The father of medicine, Avicenna, in our science and culture. Abu Ali ibn Sina (980–1037)]".Casopis Lekaru Ceskych(in Czech).119(1): 17–23.PMID6989499.

- ^"Avicenna 980–1037". Hcs.osu.edu. Archived fromthe originalon 7 October 2008. Retrieved19 January2010.

- ^""The Canon of Medicine" (work by Avicenna)".Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Archived fromthe originalon 28 May 2008. Retrieved11 June2008.

- ^Ahmad Z (2007). "Al-Zahrawi – The Father of Surgery".ANZ Journal of Surgery.77(Suppl. 1): A83.doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04130_8.x.S2CID57308997.

- ^Abdel-Halim RE (November 2006). "Contributions of Muhadhdhab Al-Deen Al-Baghdadi to the progress of medicine and urology. A study and translations from his book Al-Mukhtar".Saudi Medical Journal.27(11): 1631–1641.PMID17106533.

- ^"Chairman's Reflections: Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting".Heart Views.5(2): 74–85 [80]. 2004. Archived fromthe originalon 8 March 2013.

- ^Martín-Araguz A, Bustamante-Martínez C, Fernández-Armayor Ajo V, Moreno-Martínez JM (1 May 2002). "[Neuroscience in Al Andalus and its influence on medieval scholastic medicine]".Revista de Neurología(in Spanish).34(9): 877–892.doi:10.33588/rn.3409.2001382.PMID12134355.

- ^abTschanz DW (2003)."Arab(?) Roots of European Medicine".Heart Views.4(2).Archivedfrom the original on 3 May 2004. Retrieved9 June2013.copyArchived30 November 2004 at theWayback Machine

- ^Pormann PE,Savage-Smith E(2007). "On the dominance of the Greek humoral theory, which was the basis for the practice of bloodletting".Medieval Islamic medicine. Washington DC: Georgetown University. pp. 10, 43–45.OL12911905W.

- ^Iskandar A (2006). "Al-Rāzī".Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures(2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 155–156.

- ^Ganchy S (2008).Islam and Science, Medicine, and Technology. New York: Rosen Pub.

- ^abElgood C (2010).A Medical History of Persia and The Eastern Caliphate(1st ed.). London: Cambridge. pp. 202–203.ISBN978-1-108-01588-2.

By writing a monograph on 'Diseases in Children' he may also be looked upon as the father of paediatrics.

- ^Micheau F (1996). "The Scientific Institutions in the Medieval Near East". In Rashed R, Morelon R (eds.).Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Routledge. pp. 991–992.

- ^Barrett P (2004).Science and Theology Since Copernicus: The Search for Understanding.Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 18.ISBN978-0-567-08969-4.

- ^Blainey G (2011).A Short History of Christianity. Penguin Viking. pp. 214–215.OCLC793902685.

- ^Michael Dols has shown that the Black Death was much more commonly believed by European authorities than by Middle Eastern authorities to be contagious; as a result, flight was more commonly counseled, and in urban Italy quarantines were organized on a much wider level than in urban Egypt or Syria (Dols MW (1977).The Black Death in the Middle East. Princeton. pp. 119, 285–290.OCLC2296964.).

- ^"Page through a virtual copy of Vesalius'sDe Humanis Corporis Fabrica". Archive.nlm.nih.gov.Archivedfrom the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved21 April2012.

- ^Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2006).Brock Biology of Microorganisms(11th ed.). Prentice Hall.ISBN978-0-13-144329-7.

- ^Michael Servetus ResearchArchived13 November 2012 at theWayback MachineWebsite with a graphical study on the Manuscript of Paris by Servetus

- ^Lynch CD, O'Sullivan VR, McGillycuddy CT (December 2006)."Pierre Fauchard: the 'father of modern dentistry'".British Dental Journal.201(12): 779–781.doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4814350.PMID17183395.

- ^Williams G (2010).Angel of Death. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.ISBN978-0-230-27471-6.

- ^Cooper P (2004)."Medicinal properties of body parts".The Pharmaceutical Journal.273(7330): 900–902. Archived fromthe originalon 3 December 2008.

- ^van Der Heijden R, Jacobs DI, Snoeijer W, Hallard D, Verpoorte R (March 2004). "The Catharanthus alkaloids: pharmacognosy and biotechnology".Current Medicinal Chemistry.11(5): 607–628.doi:10.2174/0929867043455846.PMID15032608.

- ^Atanasov AG, Waltenberger B, Pferschy-Wenzig EM, Linder T, Wawrosch C, Uhrin P, et al. (December 2015)."Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: A review".Biotechnology Advances.33(8): 1582–1614.doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.08.001.PMC4748402.PMID26281720.

- ^Ezzo J, Bausell B, Moerman DE, Berman B, Hadhazy V (2001). "Reviewing the reviews. How strong is the evidence? How clear are the conclusions?".International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care.17(4): 457–466.doi:10.1017/S0266462301107014.PMID11758290.S2CID21855086.

- ^Bentley TG, Effros RM, Palar K, Keeler EB (December 2008)."Waste in the U.S. Health care system: a conceptual framework".The Milbank Quarterly.86(4): 629–659.doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00537.x.PMC2690367.PMID19120983.

- ^"WHO | Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report".WHO. Archived fromthe originalon 8 October 2020. Retrieved14 June2019.

- ^"Coverage for health care | READ online".OECD iLibrary.Archivedfrom the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved14 June2019.